Cluster Munition Monitor 2015

Casualties and Victim Assistance

Orthopedic training in Lao PDR.

© ICBL-CMC, June 2014

Casualties and Victim Assistance

(Jump to Victim Assistance)

Cluster Munition Casualties

The Monitor provides the most comprehensive statistics available on cluster munition casualties recorded annually over time, in individual countries, and aggregated globally. The Monitor has documented a total of 19,868 cluster munition casualties in 33 countries and three other areas from the mid-1960s through the end of 2014.[1] This includes casualties recorded as directly resulting from the use of cluster munitions, as well as from cluster munition remnants.[2] However, a summary total of more than 55,000 casualties globally, calculated from various country estimates, provides a better indicator of the number of cluster munition casualties.

States and other areas with cluster munition casualties (as of 1 August 2015)[3]

Note: other areas are indicated in italics.

Documentation of casualties from cluster munitions improved in the lead-up to the 2008 signing of the Convention on Cluster Munitions and continued to improve throughout the first five years following the convention’s entry into force on 1 August 2010. Before 2006, there was no global total available for casualties caused by cluster munitions. The first survey, published by Handicap International (HI) in November 2006, identified 11,044 cluster munition casualties globally.[4] These evidence-based findings contributed to a sense of outrage at the human cost of the weapon that increased the momentum of the humanitarian disarmament process for a ban on cluster munitions that would also address the needs of victims. In early 2007, HI extended its research, identifying 13,306 confirmed cluster munition casualties, with many more estimated casualties reported.[5]

Those pre-convention figures represent about two-thirds of the men, boys, women, and girls, killed and injured by cluster munitions recorded by the Monitor to date.[6] The current total includes updated data for some countries for the period before entry into force of the convention. However, even as the amount of data available on casualties has increased, one fundamental statistic has remained constant; the vast majority of the casualties of cluster munition have been civilians.

Although casualties from cluster munitions continue to be under-reported, more recent improvements in data collection highlight the widespread failure to record cluster munition casualties in past conflicts, particularly casualties that occurred during airstrikes and shelling in Southeast Asia and the Middle East.

Global casualties

Despite improvements in data collection methods since the entry into force of the Convention on Cluster Munitions, new casualties from cluster munitions occurring each year remained underreported. In many countries’ data, cluster munition casualties are not recorded separately from casualties of other types of unexploded ordnance.

In 2010-2014, cluster munition casualties were reported in 14 countries and three other areas: Afghanistan, Cambodia, DRC, Croatia, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Libya, Serbia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Ukraine, and Vietnam as well as Kosovo, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Western Sahara.

A continuing pattern of harm to civilians—particularly children and young adults—is still apparent. Children under 18 years of age accounted for half of all cluster munition casualties in 2010–2014 in countries where casualties from submunitions were disaggregated and details known.[7]

In the period 2010–2014, civilians were the majority (92%) of all cluster munition casualties where the status was recorded. Humanitarian clearance personnel accounted for 2%, and security forces—military and other security personnel as well as non-state armed group (NSAG) actors—accounted for 5%.[8] The high percentage of civilian casualties is consistent with the findings based on analysis of historical data reported previous to entry into force of the convention.[9]

Cluster munition remnants continue to be a threat to humanitarian clearance personnel—explosive ordinance disposal (EOD) teams and deminers—when clearing hazardous areas. In the period 2010–2014, at least 19 clearance personnel were casualties of submunitions, including four in 2014.[10]

In global casualty data recorded by the Monitor, which starts at the time of United States (US) cluster munition attacks in Southeast Asia in the 1960s and continues through to the end of 2014, at least 19,868 cluster munition casualties have been reported. Yet a better indicator of the extent of cluster munition casualties worldwide is the total sum of country estimates, which amounts to more than 55,000. Global projections range as high as 85,000 casualties or more, but some of those country totals are based on extrapolations from limited samples and data may be inflated.[11]

The majority of reported cluster munition casualties (64%) have occurred in States Parties to the convention, particularly Afghanistan (775), Iraq (3,035), Lao PDR (7,628), and Lebanon (721).[12]

The vast majority (15,761) of all reported casualties to date were caused by cluster munition remnants—typically explosive submunitions that failed to detonate during strikes. Another 2,783 casualties were directly caused by cluster munition use.[13] As noted in the introduction to this casualty section, casualties directly caused by use have been grossly under-reported, as were casualties among military and security personnel; therefore the actual number of casualties, both known and estimated, is massively under-represented.

Cluster munition casualties in 2014

For calendar year 2014, the Monitor received reports of 445 cluster munition casualties. Of the total, 336 occurred during cluster munition airstrikes and shelling and 106 casualties were from unexploded submunitions. The cause for three of the casualties was not reported. In 2014, 10 countries and one other area reported cluster munition casualties: Afghanistan (one), Cambodia (one), Iraq (16), Lao PDR (21), Lebanon (eight), Libya (one), South Sudan (one), Syria (383), Ukraine (seven), Vietnam (four), andKosovo (two). Almost half (46%) of all recorded casualties in Lao PDR in 2014 were caused by unexploded submunitions, demonstrating that unexploded submunition continued to present a significant threat compared to all other explosive remnants of war (ERW) in that country.

Casualties from cluster munition airstrikes and shelling in Syria and Ukraine were recorded in 2014. In 2012 and 2013, the only cluster munition casualties from attacks were in Syria.[14] Prior to Syrian cluster munition use, the last reported casualties from cluster munition attacks were recorded before the convention’s entry into force: by the United States in Yemen in 2009 and by Russia and Georgia in Georgia in 2008. In 2011, cluster munition shelling by Thailand into Cambodia resulted in 10 unexploded submunition casualties immediately following the attack.[15]

Syria had by far the most reported cluster munition casualties in 2014 (both from direct use of cluster munitions and from unexploded submunitions), as has been the case since 2012. A total of 383 cluster munition casualties were reported in Syria for 2014, including 329 casualties directly caused by cluster munition use—airstrikes and shelling. This is less than 40% of the 1,001 cluster munition casualties reported in Syria in 2013. The extreme difficulties of collecting data inside the country may have influenced the decline in the annual casualty numbers reported.

Data for Syria reported in the Monitor was collected and disaggregated according to the weapons that caused the casualties by the Violation Documentation Center in Syria (VDC) and the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR). Casualty data collection for Syria is ongoing, but efforts have been impeded by the continuing conflict. Both organizations recognize that the number of cluster munition casualties from use and due to unexploded submunitions is likely much higher than has been recorded.[16]

From 2012 through to the end of 2014, at least 1,968 cluster munition casualties were reported in Syria.

|

Cluster munition victims

“Cluster munition victims” as defined under Article 5 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions are all persons who have been killed or suffered physical or psychological injury, economic loss, social marginalization, or substantial impairment of the realization of their rights caused by the use of cluster munitions. This definition includes survivors (people who were injured by cluster munitions or their explosive remnants and lived), other persons directly impacted by cluster munitions, as well as their affectedfamilies and communities. To date data collection of cluster munition victims primarily recorded only those people killed and injured (casualties). The available information on efforts to assist cluster munition victims focuses on the survivors. Although little is known about the actual number of families and communities affected by cluster munitions, available information indicates that their needs are likely to be extensive. |

Introduction

In many ways a landmark humanitarian disarmament agreement, the Convention on Cluster Munitions is the first international treaty to make the provision of assistance to victims of a given weapon a formal requirement for all States Parties. It is also the first international humanitarian law treaty to include a reporting obligation for victim assistance. At this significant milestone, the fifth year since its entry into force on 1 August 2010, the Convention on Cluster Munitions continues to set the highest standard in obligations for the provision of assistance as well as on reporting practices on victim assistance.[17]

The objectives of the convention's victim assistance obligations were elaborated in the 2011–2015 Vientiane Action Plan adopted by States Parties at the First Meeting of States Parties in November 2010, which included a set of measurable goals and commitments.[18] This victim assistance overview includes Monitor reporting and findings from 2010 to 1 August 2015.[19]

Research shows that the Convention on Cluster Munitions, and victim assistance in humanitarian disarmament more broadly, has contributed to making more resources available to survivors, as well as people with similar needs—mostly persons with disabilities.[20] Because it requires a non-discriminatory approach to providing all forms of assistance and services, victim assistance often contributes to addressing some of the needs of persons with disabilities who are not survivors, but also have requirements—for assistance and the fulfillment of their rights—that are similar to those of cluster munition victims.

Some victim assistance efforts have reached family members of people killed by cluster munitions, as well as those who survived direct harm from cluster munitions. Assistance to so-called indirect victims is, however, far less common than assistance provided to survivors and persons with disabilities.[21]

The Convention on Cluster Munitions has provisions to safeguard against discrimination that align it with the 2008 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), which includes non-discrimination as a general principle and proscribes “discrimination of any kind on the basis of disability.”[22] In addition, the Convention on Cluster Munitions prohibits discrimination between cluster munition victims with disabilities and other persons with disabilities and requires that differences in treatment be based only on medical, rehabilitative, psychological, or socioeconomic needs.[23]

The preamble of the Convention on Cluster Munitions highlights the close relationship between the CRPD and the Convention on Cluster Munitions.[24] However, while domestic implementation of the CRPD is developing alongside the implementation of the Convention on Cluster Munitions, the structures established under the CRPD had often not yet built adequate capacity for supporting the fulfillment of the state’s obligations under either convention. In such circumstances, existing victim assistance-specific coordination remained the most viable mechanism for maintaining progress on the objectives of the Vientiane Action Plan.

By codifying the international understanding of victim assistance and its components and provisions that originally developed under the Mine Ban Treaty (1997), the Convention on Cluster Munitions has also influenced the victim assistance commitments in the Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW), particularly Protocol V and its Plan of Action on Victim Assistance (2008). It has also been reinforcing victim assistance practices under the Mine Ban Treaty’s five-year action plans. All but two of the States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions with cluster munition victims (Lao PDR and Lebanon) are also party to the Mine Ban Treaty and, as such, have also made victim assistance commitments through the Mine Ban Treaty action plans.

Non-signatories Cambodia and Vietnam are also viewed as countries with the most significant numbers of cluster munition victims in need of assistance and support.[25] Both have recognized the need to assist cluster munition victims and to provide information on their victim assistance efforts.[26]

The Convention on Cluster Munitions requires that States Parties with cluster munition victims implement specific activities with tangible outcomes, including the following:

- Ensure adequate, available, and accessible assistance;

- Provide assistance that is gender- and age-sensitive as well as non-discriminatory;

- Collect relevant data and assess the needs of cluster munition victims;

- Coordinate the implementation of victim assistance and develop a national plan;

- Integrate assistance into existing national disability, development, and human rights frameworks and mechanisms;

- Actively involve cluster munition victims in all processes that affect them; and

- Report on progress.

States Parties with responsibility for cluster munition victims should identify the resources available as well as mobilize international cooperation for victim assistance activities. The convention holds that States Parties in a position to provide international cooperation and support should direct assistance to implementation of the convention’s victim assistance obligations.[27]

Five years after the convention was adopted, victim assistance required significantly greater targeted resources to be made available in order to address the needs identified by States Parties and cluster munition victims.

Victim assistance under the Vientiane Action Plan

The Vientiane Action Plan (2010–2015) has provided a set of commitments guiding the implementation of victim assistance in all its key aspects.[28] Under the plan, states with responsibilities for cluster munition victims must increase their capacities for providing assistance.[29] Correspondingly, the States Parties in a position to provide assistance should promptly respond to requests for support “to ensure that the pace and effectiveness of these activities increases in 2011 and beyond.” They should also “strive to ensure continuity, predictability and sustainability of resource commitments.”[30]

Most of the time-bound actions of the Vientiane Action Plan were formulated to begin at the point of entry into force for each State Party. This meant that the states that ratified initially had the full five years to organize and implement the actions of the plan, while the most recent States Parties had less than two years.

Entry into force for States Parties with cluster munition victims

Government focal points

All States Parties with responsibility for cluster munition victims must designate a government focal point for victim assistance issues.[31] Under Action #21 of the Vientiane Action Plan they committed to do so within six months of the convention’s entry into force for each State Party.

Since entry into force of the convention, all States Parties with cluster munition victims rapidly designated one or more focal points, with the exception of Guinea-Bissau and Sierra Leone. Some states’ focal points have changed over the course of the past five years. Croatia designated the Croatian Mine Action Centre as its victim assistance focal point in 2011, and then transferred that responsibility to the Office for Mine Action in 2012.[32] Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) reported that its focal point was located within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 2010–2011.[33] It did not report a victim assistance focal point in 2012–2014.[34]

Assessing needs

Understanding cluster munition victims’ situations and requirements is essential to meeting needs. Under Article 5, the convention requires that States Parties make “every effort to collect reliable relevant data” and assess the needs of cluster munition victims. Under Action #22 of the Vientiane Action Plan, all necessary data should have been collected and disaggregated by sex and age, and the needs and priorities of cluster munition victims assessed within one year of the convention’s entry into force for each State Party.[35]

Monitor reporting indicates that data collection efforts in Albania, Croatia, Lao PDR, and Lebanon prioritized limited survey resources by focusing on understanding the needs of survivors and disaggregating data by age and sex, above identifying the specific number of cluster munition victims or which weapons caused the casualties. In BiH and Montenegro, the number of cluster munition victims was revised by survey, but did not record or report information on the age and sex of casualties and the needs of survivors. While no States Parties fulfilled the action within the timeframe envisioned, most States Parties took steps or saw progress in needs assessment.[36]

Authorities in Albania, in cooperation with the main victim assistance NGO Albanian Association for Assistance, Integration and Development (ALB-AID, maintained records of cluster munition survivors that detail their needs and the services received.[37] ALB-AID with support from the Albanian Mines and Munitions Coordination Office (AMMCO), expanded data collection to assess the socioeconomic and medical needs of marginalized ERW victims in several regions throughout the country.[38]

In Afghanistan, no specific national survivor survey or needs assessments have been carried out, but government ministries, the ICRC, and NGOs have collected data on the needs of survivors and other persons with disabilities for the implementation of projects. The social security registration system for persons with disabilities includes survivors. However, an independent assessment found serious problems with the system and reported that it required a significant overhaul.[39]

BiH completed a major national casualty data revision in 2009, but did not include the category of cluster munitions/unexploded submunition casualties in the questionnaire.[40] After entry into force of the convention, BiH reported in June 2011 that it had identified 225 previously unrecorded cluster munition casualties.[41] BiH has continued to identify new cluster munition casualties, however, the data has not been disaggregated by age or sex, and details were insufficient for planning or analysis.[42]

Croatia continued to pursue a commitment it made in 2009 to unify existing data on mine/ERW casualties, including cluster munition victims, to be available for use in survey and needs assessment as well as for the implementation of services.[43] A coordination group was established in 2010 to develop a unified survivor database, but progress stalled in 2011. The project restarted in 2013, and by 2014, a unified database was completed and ready for use in a needs assessment survey.[44] In early 2015, a lack of funding delayed survey implementation and alternative means to conduct the survey were being explored.[45]

In Chad, a mine/ERW survivor survey and needs assessment in the most mine/ERW-affected areas of the country was carried out by the mine action center (Centre National de Deminage, CND) with the technical support of Handicap International (HI), while it was still a signatory state in 2010. A planned countrywide mapping of all mine/ERW survivors, announced in 2011 as part of the implementation of the National Action Plan on Victim Assistance, has not been completed, while a census of mine victims and their needs was identified as a priority in 2013.[46]

In Iraq, the identification of cluster munition casualties through an ongoing survey and needs assessment was reported. Iraq’s survey of mine/ERW victims had identified 880 cluster munition victims (148 people killed, 732 injured) in five provinces as of 31 March 2014.[47] Another 16 were identified during April to December 2014.[48]

Lao PDR’s national UXO (unexploded ordnance) victims and accidents survey, which started in 2008, recorded data disaggregated by age and sex back to the 1960s.[49] However, only 15,000 mine/ERW survivors of more than 21,019 recorded were believed to still be living in 2010 (including an estimated 2,500 of 4,300 recorded cluster munition survivors).[50] This reduced the usefulness of the data for planning and implementing services. To address this, Lao PDR introduced a survivor tracking system in 10 provinces through which more than 10,000 individual survivors’ survey forms had been received by the National Regulatory Authority for the UXO/Mine Action Sector in the Lao PDR (NRA) by 2013.[51] By the beginning of 2015, all data received was entered into a database to be shared for the preparation of work plans and funding requests.[52]

The Lebanon Mine Action Center (LMAC) completed the first phase of a national needs assessment of mine/ERW and cluster munition victims, including survivors and family members, in 2010 prior to entry into force for Lebanon.[53] In 2013, Lebanon initiated another national survey and needs assessment of 690 people injured, as well as the families of people killed, which was finalized in 2014. Survey data provided the national Victim Assistance Steering Committee with information focusing mostly on medical and rehabilitation needs.[54]

In Montenegro, in 2013, Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA), in cooperation with the state-run Montenegrin Regional Centre for Underwater Demining, reported one more cluster munition casualty from 1999, in addition to the eight identified by NPA during a research study in 2006. No other details about the casualty were reported.[55]

In Mozambique, a needs assessment of a representative sample of mine/ERW survivors was completed by HI and the survivor network RAVIM (Rede para Assistência às Vítimas de Minas) in 2013, in partnership with the Ministry of Social Affairs. The survivor survey, conducted in two provinces, did not identify the type of munition or explosive device that caused injuries.[56]

Guinea-Bissau and Sierra Leone have not reported on efforts to survey and assess the needs of cluster munition victims.

Coordination and plans

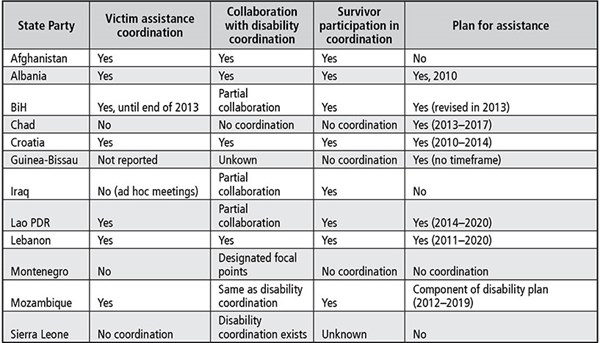

Victim assistance coordination and planning in 2010–2014

Coordination and collaboration

States Parties should integrate the implementation of the victim assistance into existing coordination mechanisms, such as those created under the CRPD (according to Action #23 of the Vientiane Action Plan), or, if there were no such mechanisms, establish a coordination mechanism within one year of the convention’s entry into force for that State Party.

However, the challenge in many States Parties where such mechanisms did exist was that the relevant coordination bodies were too weak to coordinate effectively. Therefore, victim assistance coordination could not be effectively integrated into these systems. This has been the case in states including Afghanistan, BiH, Lao PDR, and Lebanon.

Similarly, a study by HI in 2014 noted, “In some cases, the DPOs movement itself faces difficulties in coordination at the national level, in which case some [survivors’ organizations] may prefer to work separately.”[57]

Afghanistan planned to establish a national disability council or federation of disabled persons’ organizations (DPOs), but this has not been achieved.[58] While there are many coordination groups for specific disability-related issues, there has been no functioning, unified coordination mechanism.[59] Guidelines for the constitution of a national disability rights body were developed, but not implemented.[60] The Ministry of Labor, Social Affairs, Martyrs & Disabled (MoLSAMD) led efforts to revive the national disability rights body but was not successful due to the different interests of key actors.[61]

There were no mine, cluster munition, and other ERW survivors’ representative organizations on the National Council for Persons with Disabilities in BiH,which includes 10 representatives of ministries and 10 representatives of persons with disabilities.[62] A collective of NGOs, including one representing mine/ERW survivors, reported in 2014 that the national council “does not constitute an independent mechanism” in accordance with Article 33 of the CRPD.[63] According to another report, many DPOs did not consider the council inclusive or representative and reported that, as of 2014, the council had yet to show results for persons with disabilities.[64]

In Lao PDR, the National Committee for Disabled People and Elderly (NCDE) is the main disability coordination body, but the disability sector requires far greater organization and international support than the NCDE provides. There are no official disability coordination meetings for all stakeholders.[65] In 2014, DPOs reported problems with disability coordination, including frequent changes of designated disability focal points within ministries due to staff turnover, and low funding for DPOs that obstructed them from representing their members at a policy level.[66]

The National Council of Persons with Disabilities in Lebanon does not have any executive power despite its responsibility for disability social policy.[67]

National plans and strategies

Under Action #24 of the Vientiane Action Plan, States Parties without a comprehensive national plan of action should commit to adopting one that is consistent with the fulfillment of victim assistance obligations under the convention. States Parties with a plan should have adapted it to fulfill the convention.[68] This commitment had no timeframe, but was nonetheless successfully undertaken by most States Parties (see table).

Albania and Croatia adopted national victim assistance plans in 2010. Chad adopted a plan in 2012 that was extended in 2013. Lebanon introduced a victim assistance strategy as part of its 2011–2020 Mine Action National Strategy. BiH revised its victim assistance strategy (a sub-strategy of its mine action strategy) in 2012 and included references to obligations under the Convention on Cluster Munitions. Guinea-Bissau reported a national victim assistance plan in December 2013. After a period of several years planning, Lao PDR adopted a victim assistance strategy for the NRA in March 2014. Mozambique developed a national plan for victim assistance in 2013, as a component of its National Disability Plan, but it has yet to be officially adopted or put into use.

Role of survivors

The participation of cluster munition victims was essential to the development and adoption of the Convention on Cluster Munitions and their full and active inclusion remains a core principle of the convention and a legal obligation for States Parties. The convention requires that States Parties “closely consult with and actively involve cluster munition victims and their representative organisations”[69] while fulfilling victim assistance obligations. The Vientiane Action Plan holds that States Parties must actively involve cluster munition victims (Action #23) and their representative organizations in the work of the convention, placing responsibility on all States Parties—not just those with cluster munition victims—for promoting the participation of cluster munition victims.

Since 2010, the trend regarding survivor participation has been positive; in general, there has been an increase in the involvement of survivors in service provision, coordination, and policy creation.

Survivor networks, peer support organizations, and DPOs have taken on an increasingly important role in providing services to survivors. Survivors and other persons with disabilities are involved in victim assistance activities in nine States Parties with known cluster munition victims, including through the provision of ongoing services, such as prosthetics or peer support. For example, the ICRC Afghan Physical Rehabilitation Project was managed by persons with disabilities. The rehabilitation project maintained a policy of “positive discrimination,” employing and training only people with disabilities.[70] In many States Parties (including Albania, Afghanistan, BiH, Croatia, Lao PDR, and Mozambique) peer support work was carried out by survivors.

No survivor involvement in victim assistance activities was identified in Guinea-Bissau, Montenegro, or Sierra Leone.

Since the first Meeting of States Parties and the adoption of the Vientiane Action Plan in 2010, the participation of survivors in national coordination mechanisms has increased in a number of states. Survivors were included in Lao PDR’s Technical Working Group on Victim Assistance.[71] Survivors and their representative organizations participated in meetings of Croatia’s national victim assistance coordinating body. The representation and participation of persons with disabilities on Iraq’s national disability commission was included in the law mandating its establishment after advocacy efforts by the Iraq Alliance for Disability Organizations and other members of civil society.[72] In Lebanon, the National Steering Committee on Victim Assistance, coordinated by LMAC, involves national victim assistance, NGO service providers, and relevant government ministries.[73]

Progress has also been made on including survivors in consultations about the creation of policies, national victim assistance plans, and legislative measures that affect them. Survivors have been consulted or otherwise involved in the creation of national victim assistance plans in Albania, BiH, Croatia, Lao PDR, and Mozambique. In Lao PDR, representatives of survivor groups participate in consultative processes, special events, and ERW sector-wide working group meetings.[74] In Albania, a survivor network leader is also the representative of a political party that specifically represents persons with disabilities.[75]

As highlighted by Actions #30 and #31 of the Vientiane Action Plan,cluster munition victims should be considered as experts in victim assistance and included on government delegations to international meetings as well as in all activities related to the convention. There is significant scope for increased representation of survivors in international fora and the CMC has called on States Parties to make a concentrated effort to include survivors on national delegations to Meetings of States Parties and Review Conferences. Since 2010, a few states, including BiH, Croatia, and Iraq, have included a survivor as a member of their delegation to international meetings of the convention. Many more cluster munition victims participated in international meetings as part of the CMC delegation.

Progress in providing adequate assistance

The obligation for States Parties responsible for cluster munition victims to adequately provide assistance including medical care, rehabilitation, and psychological support, as well as social and economic inclusion of victims, stands at the core of the convention’s victim assistance provisions.[76] Such assistance should be age- and gender-sensitive.[77] Most States Parties have seen concrete activities undertaken to improve the delivery of adequate assistance since they committed to the measures established in the Vientiane Action Plan.

This summary overview covers developments in States Parties, while data on the provision of victim assistance in signatory states and non-signatories is available online in relevant Monitor country profiles. More details on services is available through the Monitor's Equal Basis report, which provides information on efforts to fulfill responsibilities in promoting the rights of persons with disabilities—including the survivors of landmines, cluster munitions, and other ERW—as well as in providing assistance for activities that address the needs of survivors and other persons with disabilities with similar needs in 33 countries that have obligations and commitments to enforce those rights.[78]

International organizations and NGOs carried out many, if not most, of the steps that have been taken to provide victim assistance with the backing of donor funding and in coordination with relevant government agencies and ministries.[79] These services provided the most direct and measurable assistance to persons with disabilities and war-injured persons, including cluster munition survivors. For their part, States Parties contributed by coordinating and sometimes monitoring those activities. They also provided assistance to survivors through existing healthcare, rehabilitation, and social welfare systems without having the capacity to measure the scale or impact of state-run services that reach cluster munition victims.

Availability, accessibility, and sustainability of services

Under Action #25 of the Vientiane Action Plan, States Parties committed to take immediate action to increase availability and accessibility of services, particularly in remote and rural areas where they are most often absent. In 2010, the Monitor reported on victim assistance provision in countries with cluster munition casualties, finding it to be dire in most states at that time. Among the 12 countries that are now States Parties with cluster munition victims, the Monitor found insufficient emergency medical capacity, few available services, available services that were not able to meet demand, and limited access to victim assistance services of any kind, especially for survivors in rural areas.

Despite challenges, the Monitor has identified many examples of progress in 2010–2014 in the provision of victim assistance by States Parties. The following are some highlights from the period:

- Afghanistan saw improvements in the availability of inclusive education as a result of improved physical accessibility to buildings, including schools and mosques, in urban areas following NGO activities and a national survey, which lead to a better understanding of needs. The Ministry of Health’s priority system and national development budget have been linked to a list of needs, while the ICRC and NGOs have worked to build national staff capacity.

- Albania maintained a sustainable physical rehabilitation training program. The prosthetics department, in a hospital in the cluster munition-affected Kukes region, obtained much-needed rehabilitation materials to meet increasing demand from beneficiaries in other regions.

- In BiH, more local and national NGO projects were established for economic and employment assistance to adapt to the withdrawal of international actors.

- In Croatia, the availability of emergency medical care improved with a revised contractual system in place for service providers. Psychological support services increased with the opening of a new facility that continued to improve the availability of short-term assistance.

- In Guinea-Bissau, the availability of prosthetics services increased with the opening of a rehabilitation center. In 2012, the first full year of operations of the center, more prosthetics services were provided and remained the point of greatest progress during the period.

- In Iraq,the national healthcare budget increased and, in 2013, the Iraqi and Kurdistan Ministries of Health assumed greater responsibility for the management and financing of physical rehabilitation.

- In Lao PDR, an outreach program established in 2009 has improved access to prosthetics services. Since 2012, NGO-supported first aid training, rehabilitation services, and wheelchair production has increased. Peer support activities and psychosocial assistance increased in some cluster munition-affected regions in 2013–2015.

- In Lebanon, active but often poorly funded private organizations made most of the efforts to assist persons with disabilities, while the mine action center increased its support by funding prosthetics directly for survivors in need and by ensuring they were registered to receive health and rehabilitative care.

- In Montenegro, the national health insurance system explicitly mandated free access to medical care and physical rehabilitation services for mine/ERW survivors in 2012.

- In Mozambique, as a result of programs targeting the population of persons with disabilities more generally, there were minimal increases in access to vocational training and education. All rehabilitation centers suspended the production of new prostheses in 2012, but then resumed in 2013. Peer support has increased since 2013 through survivor network outreach.

Serval programs and projects reported that the services provided did not discriminate on the basis of age or gender, however information remained limited. Many physical rehabilitation programs and economic inclusion programs disaggregated data on beneficiaries according to sex, but most did not report details indicating consideration of a gender-sensitive approach to implementation.

Many challenges remain and are most apparent in States Parties that have not managed to effectively develop much needed services in areas with gaps or failed to replace services and programs that were reduced or closed due to changes in international funding.

In Chad, no significant changes have been reported in the accessibility, availability, or quality of victim assistance services. Rehabilitation was inadequately available and there was a persistent lack of physiotherapists, psychosocial support, vocational training, and economic reintegration opportunities for survivors and persons with disabilities. There were also no significant reported changes in the accessibility, availability, or quality of victim assistance services in Sierra Leone.

Sometimes, state systems that were intended to reach persons with disabilities did not come close to fulfilling their objectives. This was the case with quota systems for employment of persons with disabilities. For example, in Afghanistan, although persons with disabilities should comprise 3% of state employees according to the law, 94% of those places were not filled and, often due to improper practices, work opportunities were taken away from persons with disabilities.[80] Disability legislation in Lebanon also stipulates a 3% quota to hire persons with disabilities for all employers. However, there was no evidence the law was enforced and it has made little or no impact.[81] The labor law of Lao PDR states that priority must be given to persons with disabilities for job placement in both the private and the public sector, but there was little awareness of this legislation among employers and no enforcement mechanisms.[82]

The principle of non-discrimination

States Parties must not discriminate against or among cluster munition victims, or between cluster munition victims and those who have injuries or disabilities from other causes, according to the Convention on Cluster Munitions.[83] During the first five years of the convention, the Monitor has not identified any discrimination specifically in favor of cluster munition victims by States Parties with Article 5 obligations.[84] Despite this, concerns about positive discrimination in the allocation of services to cluster munition victims were raised regularly by a small number of States Parties and in convention documents.

Monitor research shows that for most countries where discrimination between persons with disabilities was reported, it has been due to the privileges and special status often accorded to war veterans with disabilities, or sometimes to people from state-recognized national DPOs with influence in decision-making mechanisms.

In most countries—not only States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions—war veterans with disabilities are assigned a privileged status above that of civilian war survivors and other persons with disabilities, particularly with respect to financial allowances and other state benefits. Since 2010, this disparity continues to be a concern in countries including Afghanistan, BiH, and Lao PDR.

In 2013 and 2014, through legislative reform Albania began to tackle regulations that gave particular benefits and concessions to certain groups of persons with disabilities (persons with disabilities that have work-related disability, as well as visual impairment, and paraplegia or quadriplegia) that were not available to other persons with disabilities, including cluster munition victims. However, while making these reforms, changes were made to the system for social benefits that left many amputees without even the minor financial benefits that they previously had.[85]

In taking a rights-based approach to victim assistance, States Parties need to be mindful of the requirement not to remove existing rights, as set out in Article 4.4 of the CRPD: “Nothing in the present Convention shall affect any provisions which are more conducive to the realization of the rights of persons with disabilities and which may be contained in the law of a State Party or international law in force for that State.”[86]

Monitor reporting showed that discrimination in States Parties also manifested informally, on the basis of gender, age, ethnicity, and other prejudices.

Reporting on progress

Under Article 7 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions, States Parties are required to report on the status and progress of implementation of all victim assistance obligations. This reporting requirement is both a legal obligation and an opportunity. Victim assistance reporting under the convention is obligatory, unlike the Mine Ban Treaty’s voluntary reporting on victim assistance.

States that have made important strides in addressing the needs of cluster munition victims can share this progress with other States Parties, providing a positive example and strengthening the norm for victim assistance. States that continue to face challenges in addressing needs can clearly present what those challenges are and how technical and financial support from the international community might help overcome those challenges.

Signatory DRC included victim assistance information in its voluntary Article 7 report in 2011, becoming the first state not party to do so. In 2012, DRC submitted another voluntary report. In 2013, DRC and one other area, Western Sahara, both submitted voluntary Article 7 reports with information on victim assistance. No such reporting was noted for 2014.

All nine States Parties with cluster munition victims that submitted their Article 7 reports after entry into force have included information on victim assistance; most provided detailed information or new factual reporting.[87] The exceptions were Sierra Leone, which did not attach Form H, and Chad and Guinea-Bissau, neither of which have submitted an initial report.

Applicable national and international law

States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitionsare legally bound to implement adequate victim assistance in accordance with applicable international humanitarian and human rights law. [88] Applicable international law includes the CRPD, the Mine Ban Treaty, and the Convention on Conventional Weapons Protocol V on Explosive Remnants of War. Other instruments with relevant provisions that should be used to support the implementation of the victim assistance obligations of the Convention on Cluster Munitions include the Geneva Conventions, the 1951 Refugee Convention, the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

The Convention on Cluster Munitions has no definition or measure of what “adequate” assistance requires. However, applicable international law offers more advanced measures, including requirements such as the “highest attainable standard of healthcare.”

States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions have yet to elaborate the specific application of international humanitarian law related to protection of civilians, particularly the provisions relevant to people who have been injured and to persons with disabilities.[89] However, such provisions in the Geneva Conventions and their additional protocols, as well as customary law, may be relevant, particularly in the cases of Iraq and Afghanistan, which are among the States Parties with the largest numbers of victims and where conflict was ongoing.

States Parties’ understanding of their international humanitarian and human rights law requirements has mostly focused on a rights-based approach with particular emphasis on integrating efforts to fulfill those obligations with the implementation of the CRPD, and using national structures developed for coordination of the CRPD where they exist and are functioning adequately.

By the end of 2014, all but one of the States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions with cluster munition victims had ratified the CRPD. Many of those States Parties with cluster munition victims ratified the CRPD after the Convention on Cluster Munitions had entered into force: Afghanistan (September 2012), Albania (November 2013), BiH (March 2010), Croatia (August 2007), Iraq (March 2013), Guinea-Bissau (September 2014), Lao PDR (September 2009), Mozambique (January 2012), Montenegro (November 2009), and Sierra Leone (October 2010). Lebanon signed the convention but has not yet ratified.

In addition to international law, the Convention on Cluster Munitions’ requirement for national implementation legislation means that States Parties’ laws should ensure “the full realisation of the rights of all cluster munition victims,” as called for under Article 5. The Vientiane Action Plan specified that within one year of entry into force, States Parties were supposed to review their national laws and policies to ensure that they are consistent with their victim assistance obligations under the convention.

States Parties should have revised any inconsistent legislation by 2015. However, the process of changing national legislation often requires decisions and action of government and political groups. These groups may not understand or be aware of the Convention on Cluster Munitions victim assistance provisions. Also, those that became States Parties toward the last part of the action plan period may not have been able to progress very far with this objective. Most States Parties did not report on this objective specifically, but rather reported changes to legislation which incidentally brought them closer to fulfilling the obligations of victim assistance and the rights of cluster munition victims.

[1] Casualties include persons killed and injured.

[2] Cluster munition remnants include abandoned cluster munitions, unexploded submunitions and unexploded bomblets, as well as failed cluster munitions. Unexploded submunitions are “explosive submunitions” that have been dispersed or released from a cluster munition but failed to explode as intended. Unexploded bomblets are similar to unexploded submunitions but refer to “explosive bomblets” which have been dispersed or released from an affixed aircraft dispenser and failed to explode as intended. Abandoned cluster munitions are unused explosive submunitions or whole cluster munitions that have been left behind or dumped and are no longer under the control of the party that left them behind or dumped them. See Convention on Cluster Munitions, Art. 2 (5), (6), (7), and (15).

[3] Since the publication of Cluster Munition Monitor 2014 two countries were added to this table, Somalia and Ukraine. In 2014, for the first time, cluster munition casualties were confirmed in non-signatory Ukraine. In 2014, signatory Somalia reported on the needs of its cluster munitions victims. Statement of Somalia, General Exchange of Views, Convention on Cluster Munitions Fifth Meeting of States Parties, San José, 2 September 2014. There may have been casualties, as yet unconfirmed, in several more states. There was a credible report of unexploded submunition casualties on a weapons testing range in Zimbabwe (formerly Rhodesia). It is possible that cluster munition casualties have occurred but gone unrecorded in other countries where cluster munitions were used, abandoned, or stored in the past—such as States Parties Mauritania and Zambia and non-signatories Azerbaijan, Iran, and Saudi Arabia.

[4] Fatal Footprint: The Global Human Impact of Cluster Munitions, Preliminary Report (Brussels, HI, November 2006), p. 44.

[5] HI, Circle of Impact: The Fatal Footprint of Cluster Munitions on People and Communities (Brussels: HI, May 2007), bit.ly/MonitorHICircleofImpact2007.

[6] The Monitor collects data from an array of sources, including national reports, mine action centers, mine clearance operators, victim assistance service providers, as well as from a range of national and international media. Global cluster munition casualty data used by the Monitor includes the global casualty data collected by HI in 2006 and 2007. See, HI, Circle of Impact: The Fatal Footprint of Cluster Munitions on People and Communities.

[7] There were 112 child casualties, 113 adult casualties, and 14 of unknown age.

[8] From 2010–2014 there were 653 civilian casualties, 19 clearance personnel casualties, and 34 military casualties, of 706 casualties where the civilian status was reported.

[9] HI found that 98% of casualties were civilian by applying an equation to a small percentage of unkown casualties based on the percentage of casualties for which civilian statues was known. Of the number of known casualties the percentage of civilians was some 94%. Data used by the Monitor includes global casualty data collected by HI in 2006 and 2007. The addition of new data sources over time did not significantly change the percentage of civilian casualties. See, HI, Circle of Impact: The Fatal Footprint of Cluster Munitions on People and Communities (Brussels: HI, May 2007), bit.ly/MonitorHICircleofImpact2007.

[10] This total does not include NSAG fighters or civilians clearing cluster munition remnants.

[11] See also, HI, Circle of Impact: The Fatal Footprint of Cluster Munitions on People and Communities (Brussels: HI, May 2007), bit.ly/MonitorHICircleofImpact2007. “A conservative estimate indicates that there are at least 55,000 cluster submunitions casualties but this figure could be as high as 100,000 cluster submunitions casualties.”

[12] The Monitor has recorded 12,725 casualties in States Parties through to the end of 2014.

[13] For another 1,324 casualties documented it was not specified how many were due to strikes.

[14] There may have been casualties due to the use of a type of cluster munition in Myanmar in 2013, but no details were available.

[15] However, no casualties directly caused by the shelling were reported.

[16] In July 2015, the SNHR informed the Monitor that it believes that the number of cluster munition casualties, including persons injured, is likely far more than what they had been able to report, noting that “the Syrian regime relies greatly on using cluster munitions.” The VDC reported that the statistics available through casualty reports on its website database are likely far lower than those caused by the actual use of cluster munitions and that this “is of course due to the hardship of collecting data inside of the different geographic [locations] in Syria and the pursuit of human rights activists by all military parties." Email from Amir Kazkaz, VDC, 8 March 2015; and email from Fadel Abdul Ghani, SNHR, 27 July 2015.

[17] See Article 5 and Article 7.k. of the Convention on Cluster Munitions. In contrast, the text relevant to victim assistance in Mine Ban Treaty (1997) only applies to parties in a position to provide assistance, as does the text of Article 8.2 of the Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW) Protocol V on Explosive Remnants of War (2003).

[18] Cluster munition victims include survivors (people who were injured by cluster munitions or their explosive remnants and lived), other persons directly impacted by cluster munitions, as well as their affectedfamilies and communities. Most cluster munition survivors are also persons with disabilities. The term “cluster munition casualties” is used to refer both to people killed and people injured as a result of cluster munition use or by cluster munition remnants.

[19] The majority of information provided was on the basis of annual calendar year updates for the period 1 January 2010 to December 2014, with additional information to 1 August 2014 included as available.

[20] See individual country profiles; and the Monitor, “Frameworks for Victim Assistance: Monitor key findings and observations,” 3 December 2013, bit.ly/MonitorVAFrameworks2013.

[21] For more information on services provided to indirect victims see, ICBL-CMC, “Victim Assistance and Widowhood” (Briefing Paper), 23 June 2015, bit.ly/MonitorVAWidowhood2015.

[22] See, Convention on Cluster Munitions, Article 5.2.e; CRPD, Article 3.b; and CRPD, Article 4.1.

[23] Convention on Cluster Munitions, Article 5.2.e. This is also relevant to with International Humanitarian Law, including Additional Protocol II of the Geneva conventions, in regard to persons wounded: “There shall be no distinction among them founded on any grounds other than medical ones.” Article 7.2., Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts (Protocol II), 8 June 1977. bit.ly/MonitorCMM15VAf23.

[24] The preamble states: “Bearing in mind the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities which, inter alia, requires that States Parties to that Convention undertake to ensure and promote the full realisation of all human rights and fundamental freedoms of all persons with disabilities without discrimination of any kind on the basis of disability.”

[25] “Draft Oslo Progress Report,” CCM/MSP/2012/WP.1, undated, pp. 7 and 9, www.clusterconvention.org/files/2012/06/Oslo-Progress-Report-13-7-2012-2_final.pdf; and “Lusaka Progress Report,” Lusaka, (corrected) 13 September 2013, p. 9, www.clusterconvention.org/files/2013/04/LPR-with-annex-as-corrected.pdf.

[26] Cambodia and Vietnam have reported on their implementation efforts in accordance with the convention’s specific requirements of planning, coordination, and the integration of victim assistance into rights-based frameworks, such as the CRPD. Statement of Cambodia, Convention on Cluster Munitions Third Meeting of States Parties, Oslo, 12 September 2012, bit.ly/MonitorCMM15VAfn26a; and statement of Vietnam, Convention on Cluster Munitions Second Meeting of States Parties, Beirut, 14 September 2012, bit.ly/MonitorCMM15VAfn26b. Vietnam stated that it is “among the countries most affected by cluster munitions and other explosive remnants of war.” It also stated, “Viet Nam has signed the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and adopted a Law on Persons with Disabilities, which provides an important legal framework for the care for and assistance to victims of ERW.” Vietnam identified the Ministry of Labour, War Invalids and Social Affairs as the focal point for victim assistance and is developing a Victim Assistance Action Plan and Standard Guidelines on Victim Assistance.

[27] Convention on Cluster Munitions, Article 6.7.

[28] The Vientiane Action Plan includes 14 victim assistance actions, with 10 detailed and time-bound victim actions specific to countries with cluster munition victims, and three other actions relating to victim assistance in States Parties.

[29] Vientiane Action Plan, Action #20.

[30] Vientiane Acton Plan, Action #37; and Action #38.

[31] Convention on Cluster Munitions, Article 5.1g.

[32] Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2011), Form H,; and Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2012), Form H, bit.ly/MonitorArt7ClusterMunitions.

[33] Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2010), Form H,; and Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2011), Form H, bit.ly/MonitorArt7ClusterMunitions.

[34] Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2012), Form H,; Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2013), Form H; and Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2014), Form H, bit.ly/MonitorArt7ClusterMunitions.

[35] Such data should be made available to all relevant stakeholders and contribute to national injury surveillance and other relevant data collection systems for use in program planning.

[36] With the possible exception of Albania, which had an ongoing needs assessment survey in place prior to entry into force of the Convention on Cluster Munitions.

[37] Interview with Jonuz Kola, Executive Director, Albanian Association for Assistance, Integration and Development (ALB-AID), Sarajevo, 13 April 2010; and statement of Albania, Convention on Cluster Munitions Intersessional Meetings, Session on Victim Assistance, Geneva, 28 June 2011.

[38] Email from with Jonuz Kola, ALB-AID, 20 May 2015; and interview with Izet Ademaj and Zabit Cukes, ALB-AID, Tirana, 20 May 2015.

[39] Independent Joint Anti-Corruption Monitoring and Evaluation Committee Vulnerability to Corruption, “Assessment of the Payment System for Martyrs and Persons Disabled by Conflict,” 3 June 2015, pp. 2–9, www.mec.af/files/2015_06_03_MOLSAMD_VCA_%28English%29.pdf.

[40] Statement of BiH, Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Standing Committee on Victim Assistance and Socio-Economic Reintegration, Geneva, 24 June 2010; and BHMAC data collection forms in Suzanne L. Fiederlein, Landmine Casualty Data: Best Practices Guidebook (Harrisonburg: Mine Action Information Center, 2008), p. 39.

[41] Statement of BiH, Convention on Cluster Munitions Intersessional Meetings, Session on Victim Assistance, Geneva, 28 June 2011.

[42] Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2014), Form H.

[43] Statement of Croatia, Mine Ban Treaty Tenth Meeting of States Parties, Geneva, 1 December 2010; and statement of Croatia, Convention on Cluster Munitions Intersessional Meetings, Session on Victim Assistance, Geneva, 28 June 2011.

[44] Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for the calendar year 2014), Form H; and email from Hrvoje Debač, Government Office for Mine Action, 23 March 2014.

[45] Emails from Maja Dundov Gali, CROMAC, 7 April 2015; and Marija Breber, MineAid, 10 April 2015.

[46] ICRC Physical Rehabilitation Programme (PRP), “Annual Report 2014,” Geneva, 2015; response to Monitor questionnaire by Zienaba Tidjani Ali, CND, 2 April 2013; email from Zakaria Maiga, ICRC, 29 March 2013; and statement of Chad, Mine Ban Treaty Twelfth Meeting of States Parties, Geneva, 4 December 2012.

[47] Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (Initial report 2013), Form H.

[48] Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (from April to December 2014), Form H.

[49] The National Regulatory Authority (NRA), “The Unexploded Ordnance (UXO) Problem and Operational Progress in the Lao PDR Official Figures,” 2 June 2010; and NRA, “National Survey of UXO Victims and Accidents Phase 1,” Vientiane, February 2010, p. 39.

[50] Statement of Lao PDR, Convention on Cluster Munitions First Meeting of States Parties, Vientiane, 11 November 2010; and Lao PDR voluntary Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for the period to the end of 2010), Form J.

[51] Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (calendar year 2013), Form H, bit.ly/MonitorArt7ClusterMunitions.

[52] Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (calendar year 2014), Form H; and interview with Bountao Chanthavongsa, NRA, Vientiane, 11 June 2015.

[53] The survey covered people affected in the period from July 2006 to the end of 2010. Email from Col. Rolly Fares, Head of Information Management and Victim Assistance Section, LMAC, 31 May 2011.

[54] Email from Brig. Gen. Elie Nassif, Director, LMAC, 13 May 2015.

[55] No other details about the casualty were reported. Cluster Munition Remnants in Montenegro: Non-technical Survey of Contamination and Impact (Podgorica: Regional Centre for Underwater Demining, Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA), May 2013), p. 27.

[56] There were casualties from incidents involving cluster munition remnants in Mozambique, though these were not distinguished from ERW in the data and would require a survey to identify them. Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for the calendar year 2012), Form H; statement of Mozambique, Convention on Cluster Munitions Second Meeting of States Parties, Beirut, 16 September 2011; and interview with António Belchior Vaz Martin, IND, and Mila Massango, Head of International Affairs, IND, in Geneva, 22 June 2010.

[57] “Victim assistance issue briefs: how to ensure mine/ERW survivors benefit from and participate in disability-inclusive development,” Brussels, 2014, bit.ly/MonitorCMM15VAf57.

[58] Response to Monitor questionnaire by Mine Action Coordination Centre of Afghanistan (MACCA) (consolidated questionnaire including information from Ministry of Education, MoLSAMD, and Ministry of Public Health), April 2015.

[59] Response to Monitor questionnaire by Juliette Coatrieux, Programme Support Officer, HI, 26 April 2015.

[60] Email from Samiulhaq Sami, HI, Kabul, 14 October 2014.

[61] Response to Monitor questionnaire by Juliette Coatrieux, HI, 26 April 2015.

[62] Response to Monitor questionnaire by Esher Sadagic, BHMAC, 27 May 2013; and statement of BiH, Mine Ban Treaty Thirteenth Meeting of States Parties, Geneva, 3 December 2013.

[63] Report for the Universal Periodic Review Bosnia and Herzegovina Informal Coalition of Non-governmental Organisations for Reporting on Human Rights, p. 5, bit.ly/MonitorCMM15VAf63. See also, CRPD Article 33 - National implementation and monitoring, www.un.org/disabilities/default.asp?id=293.

[64] Light for the World/MyRight, “Report for the Universal Periodic Review–second cycle Bosnia and Herzegovina,” March 2014, pp. 2, 6, bit.ly/MonitorCMM15VAf64.

[65] Notes from Monitor field mission to Lao PDR, 11–12 June 2015.

[66] “Universal Periodic Review (UPR 18),” A Stakeholders report prepared by Lao Disability Network, Lao PDR Coordinated by: Lao Disabled People’s Association (LDPA), undated, but 2014,bit.ly/MonitorCMM15VAf66.

[67] Lebanese Coalition of Organizations of Disabled Persons, Questionnaire response to Special Rapporteur on the rights of persons with disabilities on the right of persons with disabilities to social protection, May 2015, www.ohchr.org/documents/issues/disability/socialprotection/civil_society/lcdp_lebanon_eng.doc.

[68] Together with the plan States Parties should develop a budget.

[69] Convention on Cluster Munitions, Article 5.2.f.

[70] Responses to Monitor questionnaires by Alberto Cairo, ICRC, Kabul, 26 April 2014, and 14 April 2015.

[71] Notes from Monitor field mission to Lao PDR, 11–12 June 2015.

[72] Email from Moaffak Alkhfaji, Director, Iraqi Alliance for Disability (IADO), 29 June 2013.

[73] Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2012), Form H.

[74] The survivor groups include the Lao Disabled People Association, HI, Lao Ban Advocates Project, and Quality of Life Association. Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2014), Form H.

[75] Interview with Izet Ademaj and Zabit Cukes, ALB-AID, Tirana, 20 May 2015.

[76] Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 5.1, which applies with respect to cluster munition victims in areas under the States Parties jurisdiction or control.

[77] Children require specific and more frequent assistance than adults. Women and girls often need specific services depending on their personal and cultural circumstances. Women face multiple forms of discrimination, as survivors themselves or as those who survive the loss of family members, often the husband and head of household.

[78] See, ICBL-CMC, “Equal Basis 2014: Access and Rights in 33 Countries,” December 2014, bit.ly/MonitorEqualBasis2014.

[79] Such contributions are consistent with Article 6.7 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions, which specifies that assistance can be provided “inter alia, through the United Nations system, international, regional or national organisations or institutions, the International Committee of the Red Cross, national Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies and their International Federation, non-governmental organisations or on a bilateral basis.”

[80] Independent Joint Anti-Corruption Monitoring and Evaluation Committee Vulnerability to Corruption, “Assessment of the Payment System for Martyrs and Persons Disabled by Conflict,” 3 June 2015, p. 5, www.mec.af/files/2015_06_03_MOLSAMD_VCA_%28English%29.pdf.

[81] United States Department of State, “2014 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Lebanon,” Washington, DC, 25 June 2015, www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/humanrightsreport/index.htm - wrapper.

[82] “Universal Periodic Review (UPR 18),” A Stakeholders Report prepared by Lao Disability Network, Lao PDR, Coordinated by: Lao Disabled People’s Association (LDPA), undated, but 2014, bit.ly/MonitorCMM15VAf66.

[83] Article 5.2.e.

[84] Such discrimination by donors and implementers in the sphere of landmine/ERW victim assistance more broadly has been identified by HI, as well as the perception of such discrimination by persons with disabilities in some countries. In 2014, HI reported that services targeting only landmine and ERW survivors still existed, and other practices which may favor survivors were reported, but did not specify this was occurring with cluster munition survivors and victims in States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions. See, “Victim assistance issue briefs: how to ensure mine/ERW survivors benefit from and participate in disability-inclusive development,” Brussels, 2014, bit.ly/MonitorCMM15VAf57.

[85] Email from Jonuz Kola, ALB-AID, 3 August 2015.

[86] CRPD, Article 4.4, www.un.org/disabilities/default.asp?id=264.

[87] Afghanistan, Albania, BiH, Croatia, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Montenegro, and Mozambique included victim assistance information in Form H of their Article 7 reporting during the period.

[88] Convention on Cluster Munitions, Article 5.1.

[89] These provisions can be seen, for example, in the ICRC, Customary IHL Database, Rule 138. The elderly, disabled and infirm affected by armed conflict are entitled to special respect and protection, www.icrc.org/customary-ihl/eng/docs/v1_cha_chapter39_rule138; Rule 110. Treatment and Care of the Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked, www.icrc.org/customary-ihl/eng/docs/v1_rul_rule110; and Rule 111. Protection of the Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked against Pillage and Ill-Treatment, www.icrc.org/customary-ihl/eng/docs/v1_rul_rule111.