Landmine Monitor 2016

Casualties & Victim Assistance

Casualties

Overview

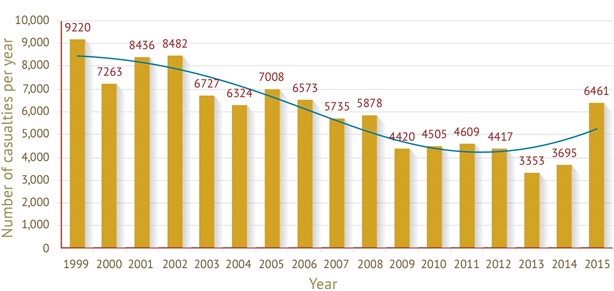

In 2015, there was a sharp rise in the number of casualties caused by landmines, including victim-activated improvised explosive devices (IEDs) (also called victim-activated improvised landmines), as well as cluster munition remnants,[1] and other explosive remnants of war (ERW)—henceforth mines/ERW. For 2015, the Monitor recorded 6,461 mine/ERW casualties, marking a 75% increase from 3,695 casualties recorded for 2014.[2] Casualties, the people killed and injured by mines/ERW, were identified in a total of 61 states and other areas in 2015.[3]

This sharp increase was due to more mine/ERW casualties recorded in armed conflicts in Libya, Syria, Ukraine, and Yemen in 2015, as compared with previous years. In 2015, there was also increased availability of casualty data for persons injured in some countries, particularly Libya and Syria. The casualty total in 2015 marked the highest number of annual casualties by victim-activated IEDs (also called improvised mines) recorded by the Monitor.

Despite the overall increase, declining casualty rates were recorded in the majority of states and other impacted areas. Recorded casualties decreased in 34 countries and areas (726 total decrease) compared to 2014, while the number of casualties recorded in 2015 increased in 31 (3,492 total increase). The group of 34 includes Cambodia and Colombia, two States Parties that remain among those with the highest casualties, but for which rates have been declining over the past years.[4] Together just four countries—Libya, Syria, Ukraine, and Yemen—account for an increase of 3,218 casualties from 2014, representing the majority of the total annual increase of 3,492 casualties in the group of 31.[5]

Number of mine/ERW casualties per year (1999–2015)

The spike represented the highest annual total of mine/ERW casualties recorded in a decade (since 2006). The 2015 casualty increase of 2,766 more people killed and injured than recorded in 2014 also marks the most serious disturbance in an overall trend of progressively fewer annually recorded mine/ERW casualties for the period since the Mine Ban Treaty entered into force in 1999. This reflects an average incidence rate of almost 18 mine/ERW casualties per day in 2015, compared to 10 casualties per day in 2014. However, in 1999 there were 25 mine/ERW casualties per day on average.[6]

The Monitor has recorded more than 100,000 mine/ERW casualties for the 17-year period since its global tracking in began in 1999,[7] including some 73,000 new survivors.[8] Mine/ERW incidents impact not only the direct casualties—the boys, girls, women, and men who were killed, as well as the survivors—but also members of their families struggling under new physical, psychological, and economic pressures. As in previous years, there was no substantial data available on the numbers of those people indirectly impacted as a result of mine/ERW casualties.

Of the total of 6,461 mine/ERW casualties the Monitor recorded for 2015, at least 1,670 people were killed and another 4,785 people were injured; for six casualties, it was not known if the injured person survived. This was the lowest figure for unknown outcome of injury or death for annual mine/ERW casualties since Monitor recording began in 1999.

Civilians represented the vast majority of casualties as compared to military and security forces,[9] where the civilian status was known, continuing a clear trend of civilian harm over time: 78% in 2015—similar to the 80% of civilian casualties recorded in 2014 and almost identical to the 79% recorded for 2013.[10]

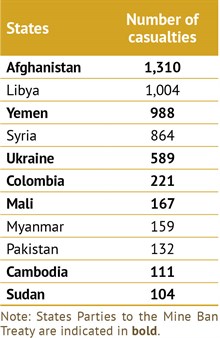

Some three-quarters (74%, or 4,755) of all mine/ERW casualties recorded for 2015 occurred in five states, all of which are conflict-affected: Mine Ban Treaty States Parties Afghanistan, Ukraine, and Yemen, as well as states not party Syria and Libya.

States with 100 or more recorded casualties in 2015

Of the total casualties in 2015, 61% (3,935) occurred among 51 Mine Ban Treaty States Parties, compared to 71% (2,610) in 37 States Parties recorded for 2014.[11]

Afghanistan continued to record the highest number of casualties in 2015, although the annual total for the country remained almost the same, with just 14 casualties more than in 2014.

Several significant country-level increases in annual casualty totals in 2015 were influenced in part by progress, albeit likely temporary advances, in data collection despite conflict and insecurity.

Of the 1,004 total mine/ERW casualties for Libya in 2015, 982 were recorded in the Libyan Mine Action Center (LibMAC) database.[12] The vast majority of these casualties—935 persons reported injured by ERW—were recorded during surveys at two hospitals in Tripoli.[13] Those hospitals do not have reliable and updated databases, therefore casualty numbers were likely under-reported.[14]

In Syria, a significant increase in mine/ERW casualties in 2015 was influenced by the availability of data from an extensive survey project of conflict-injured persons, including refugees. Syria had 864 recorded casualties in 2015, compared to 174 in 2014. The majority of mine/ERW casualties for 2015 (551) were from records of persons injured compiled and recorded as casualties of unspecified mines by Handicap International (HI) in data on the needs of conflict survivors.[15] This marked the first time since the beginning of the conflict that a substantial dataset on persons injured by mines/ERW in Syria was available. Data on injured persons was collected through interviews with displaced people and refugees in Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon.[16] Detailed data on fatalities was collected and disaggregated according to the weapons involved by the Violation Documentation Center in Syria (VDC) and the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR).[17]

In Yemen, there were 988 mines/ERW casualties identified in 2015, the majority (812) reported by the ICRC as having been admitted to healthcare facilities in the calendar year.[18] ICRC data was not disaggregated by age or gender; however, the ICRC noted that most casualties were male.[19] In 2014, the Monitor identified 24 casualties from mines/ERW. The ICRC reported just five mine/ERW casualties receiving treatment in 2014.[20]

Due to ongoing conflict in Iraq, the number of mine/ERW casualties continued to be significantly under-recorded. Only 58 mine/ERW casualties were recorded in Iraq, and as in past years, the number is thought to be much higher. Unlike in Afghanistan where the UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) records data more completely,[21] a complete lack of disaggregation between command-detonated IEDs, including emplaced, body-borne, and vehicle-borne devices, and presumably victim-activated IEDs meant that the number of mine casualties remained obscured in Iraq.[22] In south and central Iraq, data for 2015 cluster munition casualties were not disaggregated due to the difficulties caused by continuing military operations against the so-called Islamic State (IS, also known as ISIS or ISIL) preventing mine action casualty data recording coordination with relevant authorities in order to classify and complete the data.[23]

As in previous years, the mine/ERW casualties identified in 2015 only include recorded casualties, not estimates. Based on the Monitor research methodology in place since 2009, it has been estimated that there are up to approximately 25–30% additional casualties each year that are not captured in the Monitor’s global mine/ERW casualty statistics, with most occurring in severely affected countries and those experiencing conflict.

The level of under-reporting of casualties has declined over time, as many countries have initiated and improved casualty data-collection mechanisms and the sharing of this data. In 2015, the number of casualties missed in national annual reporting was likely reduced in some countries experiencing conflict, thus contributing to a higher global casualty total. Nonetheless, in many states and areas, numerous casualties go unrecorded; therefore the true casualty figure is likely significantly higher in some countries.

Casualty demographics[24]

There were at least 1,072 child casualties in 2015. Child casualties in 2015 accounted for 38% of all civilian casualties for whom the age was known.[25] This was similar to the 39% recorded for 2014 and for 2012, but a significant decrease from many past years, including 2013 with 46%. Children were killed (347) and injured (725) by mines/ERW in 36 countries and other areas in 2015.[26]

As in previous years, in 2015 the vast majority of child casualties where the sex was known were boys (82%).[27]

ERW caused the most child casualties (456, or 43%), followed by victim-activated improvised mines (319, or 30%). For more information on child casualties and assistance see the annual Monitor fact sheet on landmines/ERW and children.

Mine/ERW casualties by age in 2015

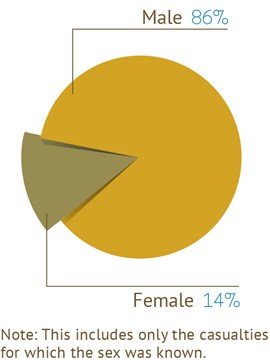

In 2015, female casualties made up 14% of all casualties for which the sex was known (551 of 4,026).[28]

Mine/ERW casualties by sex in 2015

In 2015, there were 46 casualties identified among deminers (six deminers were killed and 40 injured) in 10 states.[29] This represented a similar finding as for 2014, when 53 deminer casualties were recorded in 10 states. It was, however, about half of the average of 105 casualties among deminers per year since 1999.

Between 1999 and 2015, the Monitor identified more than 1,600 deminers who were killed or injured while undertaking clearance operations.[30]

Mine/ERW casualties by civilian/military status in 2015

Civilian casualties represented 78% of casualties in 2015 where the civilian/military status was known (2,990 of 3,809).

The countries with the most military casualties in 2015 were Ukraine (273) and Colombia (158). Mali, with 72 military casualties (including peacekeeping forces), was the third highest. The next highest numbers of military casualties in 2015 were in Syria (64) and Pakistan (57).

Mines/ERW causing casualties

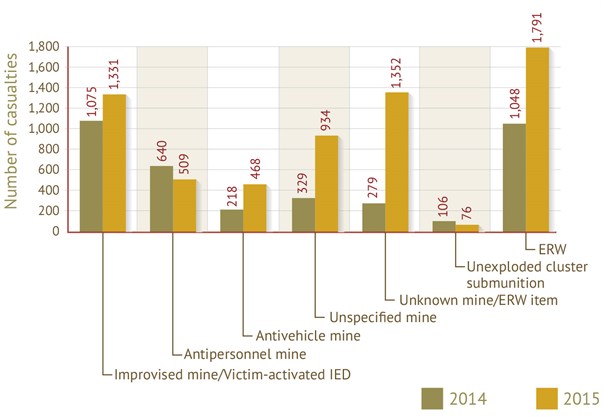

In 2015, landmines—including factory-made antipersonnel mines (509, or 8%), victim-activated improvised mines (1,331, or 21%), antivehicle mines (468, or 7%), and unspecified mine types (934, or 14%)—caused the majority of all casualties (3,233, or 50% combined). Unexploded submunitions caused 76 casualties (or 1%) and other ERW 1,791 casualties (or 28%). Unknown mine/ERW items caused 1,352 casualties, or 21% of the annual total.

Casualties by type of explosive device in 2014 and 2015[31]

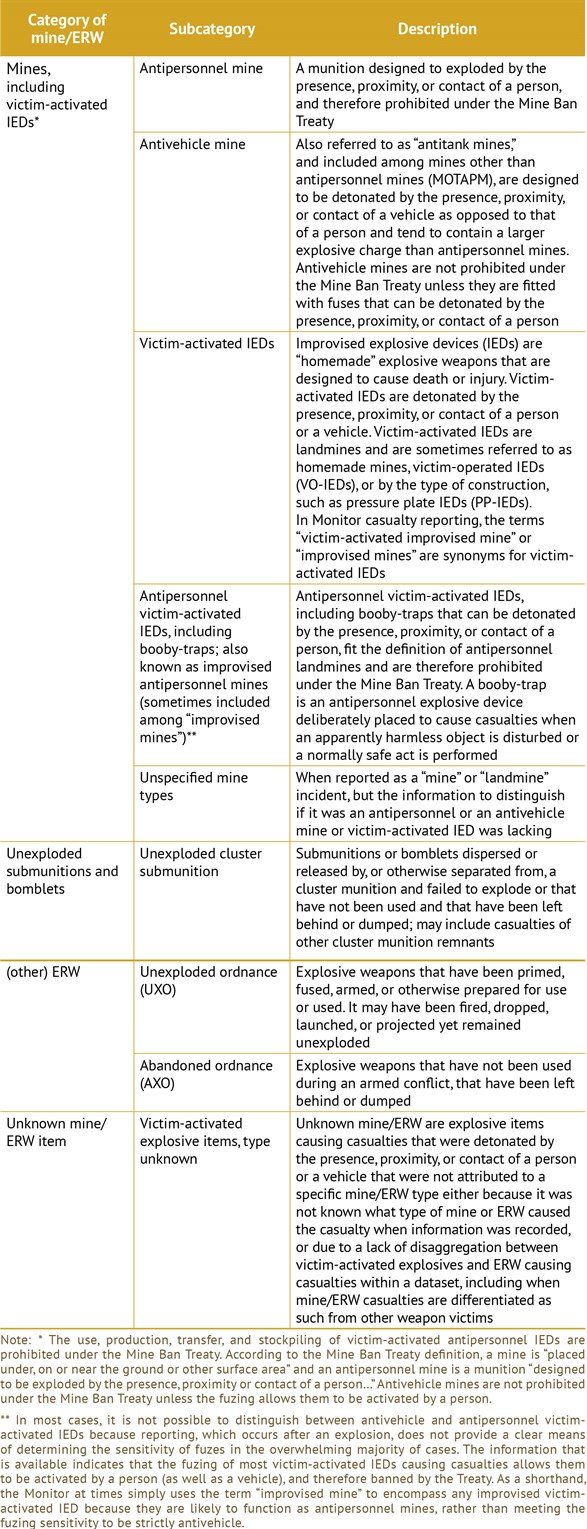

Mine/ERW types causing casualties

The 1,331 victim-activated IED/improvised mine casualties recorded for 2015 was the highest annual total of such casualties recorded since 1999, the next highest number recorded was 1,169 in 2012. Casualties from victim-activated IEDs were identified in 13 states in 2015.[32] Historically, the number of victim-activated IED casualties was under-reported because such casualties were included in data as caused by unspecified mine types and unknown mine/ERW items. Starting in 2008, the Monitor began identifying more casualties from these improvised antipersonnel mines, likely due in part to an increase in their use and also to improved data collection that made it possible to better discern between factory-made antipersonnel mines and victim-activated IEDs, and between command-detonated IEDs and victim-activated IEDs in some countries. However, casualties of improvised antipersonnel mines in Colombia[33] are recorded as antipersonnel landmine casualties by the mine action authorities and for consistency this definition is retained in Monitor reporting, there being no functional need for reclassification. Casualties of improvised antipersonnel mines in Myanmar, Yemen, and Ukraine[34] are also likely to be included among those recorded as antipersonnel landmine casualties.

Casualties recorded as due to unspecified mine types increased significantly from 329 in 2014 to 934 in 2015. This was mostly attributable to 719 casualties in the data for Syria, making up 77% of the category in 2015, likely due to nonspecific default categorization of different types of mine/ERW casualties as “landmine casualties.” The remaining 219 casualties of unspecified mine types were recorded in 10 states.[35]

Casualties recorded as caused by antipersonnel mines decreased from 640 to 509 in 2015, with the greatest decreases reported in Colombia, from 251 in 2014 to 208 (down 17%); Myanmar, from 100 in 2014 to 66 (down 34%); Afghanistan, from 52 to 13 (down 75%); and Cambodia, from 37 in 2014 to 13 (down 65%). At least 40 antipersonnel mine casualties were reported for Ukraine in 2015.

In 2015, antivehicle mines caused at least 468 casualties in 18 states and other areas.[36] The states with the greatest numbers of casualties reported from antivehicle mines were Ukraine (147), Pakistan (73), and Syria (68). In 2014, antivehicle mines caused 218 casualties.[37]

In 2015, the number of casualties of unknown mine/ERW items in the Monitor global total jumped to 1,352, compared to just 279 in 2014. For 2015, 69% (932) of all casualties of unknown mine/ERW items were recorded in Yemen, where most such injured persons were documented under a general default category of mine/ERW casualties in injury surveillance data.[38] The remaining 420 casualties of unknown mine/ERW items occurred in 14 countries and one other area.[39] In 2015, 28% of all casualties (1,791) were caused by ERW in 40 states and areas.[40] Children (495) made up 60% of ERW casualties in 2015, when the age group was recorded.[41]

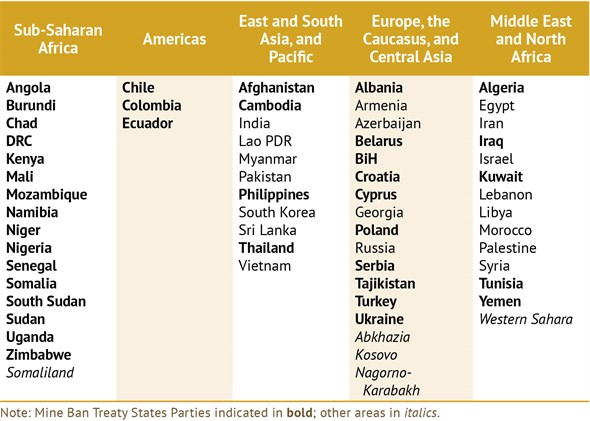

States/areas with mine/ERW casualties in 2015

Victim Assistance

Introduction

The Mine Ban Treaty has made progress, but has not yet attained its ultimate goal of alleviating human suffering caused by landmines. Importantly, it is the first disarmament or humanitarian law treaty in which States Parties commit to provide “assistance for the care and rehabilitation, including the social and economic reintegration” of those people harmed by a specific type of weapon.[42]

Victim assistance aims to achieve comprehensive rehabilitation of survivors and the full inclusion of survivors and their families in wider society, as well as ensuring that the same assistance is available to affected communities. That assistance includes: data collection and needs assessment with referral to emergency and continuing medical care; physical rehabilitation, including prosthetics and other assistive devices; psychological support; social and economic inclusion; and the adoption or adjustment of relevant laws and public policies. Preferably, such assistance is to be provided through a comprehensive approach comprised of all of the above elements.

Victim assistance, in practice, addresses the overlapping and interconnected needs of persons with disabilities, including survivors[43] of landmines, cluster munitions, explosive remnants of war (ERW), and other weapons, as well as people in their communities with similar requirements for assistance. In addition, some victim assistance efforts reach family members of casualties or those who have suffered trauma, loss, or other harm due to mines/ERW. All of these people are considered “mine victims” according to the accepted definition of the term, which includes survivors as well as affected families and communities[44]—although to date most victim assistance efforts have targeted survivors and other persons with disabilities.

In June 2014, at the Mine Ban Treaty Third Review Conference, States Parties adopted and committed to the Maputo Action Plan, which includes a set of actions that would advance victim assistance through to 2019.[45] States Parties recognized that completion of mine clearance obligations “is within reach.” They also formally declared that they remain very much aware of their “enduring obligations to mine victims.”[46] Victim assistance is an ongoing responsibility in all states with survivors and affected communities, including those countries that are mine-affected and those that have been declared mine-free.

While specific victim assistance efforts have been demonstrated to benefit survivors and other persons with disabilities, it has been noted that “there is little evidence that broader development, human rights and humanitarian efforts also reach victims.”[47] The Maputo Action Plan and provisions of the Convention on Cluster Munitions indicate that a long-term solution to addressing the needs of victims involves “an integrated approach to victim assistance” whereby:

- Specific victim assistance efforts act as a catalyst to advance the inclusion and well-being of survivors, other persons with disabilities, indirect victims and other vulnerable groups; and

- Broader efforts reach victims amongst overall beneficiaries.[48]

This dual approach is to be implemented until such time as “mainstream efforts” are demonstrated to be inclusive of, and fulfil the obligations that states have to, survivors and indirect victims.[49]

As shown by the many successful practices and activities over time, victim assistance is not inherently complicated.[50] However, many challenges do remain to ensure access to sustainable services, to remove the barriers to the full participation of survivors and indirect victims in their societies, and to create tangible improvements in their wellbeing and quality of life.

The Monitor has tracked the progress of programs and activities that benefit mine/ERW survivors, families, and communities under the Mine Ban Treaty and its subsequent five-year action plans since 1999. This overview reports on the year 2015, with relevant updates into October 2016 when available. It covers the activities and achievements in 31 States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty with significant numbers of mine/ERW victims in need of assistance.[51]

Monitor reporting demonstrates that it will require active cooperation and stronger determination to overcome challenges and allocate the resources necessary to address the enduring obligations of victim assistance. Dedicated funding for victim assistance, which has, in practice, contributed to fulfilling the rights of survivors and other persons with disabilities, has been declining. Other frameworks that could address the rights and needs of victims, including disability-inclusive development and poverty reduction efforts, have not yet been able to ensure the sustainability of such assistance or mitigate the impact of shrinking resources. As stated by Thailand, Chair of the Mine Ban Treaty’s Committee on Victim Assistance, “Victim assistance requires long-term and continual efforts on the part of States to support all victims.”[52]

Mine Ban Treaty States Parties with significant numbers of survivors and needs[53]

Treaty machinery and victim assistance

According to Action #16 of the Maputo Action Plan, all States Parties will seize every opportunity to raise awareness of the imperative to address the needs and guarantee the rights of mine victims. A Committee on Victim Assistance was formed at the Mine Ban Treaty’s Third Review Conference in Maputo with the purpose to “support States Parties in their national efforts to strengthen and advance victim assistance.” The committee is mandated to ensure a balance between ongoing discussions on victim assistance within the framework of the Mine Ban Treaty itself. It is also tasked with taking the discussion on meeting the needs and guaranteeing the rights of mine victims to fora of other frameworksthat address relevant issues, including those related to disarmament and disability rights.[54]

The committee, and Thailand in particular, took an active role in promoting victim assistance inside and outside the treaty. For example, the Bangkok Symposium on Landmine Victim Assistance: Enhancing a Comprehensive and Sustainable Mine Action, held on 15–17 June 2015 in Bangkok, was organized in collaboration with the Mine Ban Treaty Implementation Support Unit. A side event on the margins of the intersessional meetings in Geneva in May 2016 explored “gold standards” in assistance. In September 2016, the Committee on Victim Assistance held a side event during the 33rd session of the Human Rights Council entitled “Promoting mine victims’ rights: making their rights real,” to encourage the sharing of experiences and challenges in integrating victim assistance into broader human rights and disability frameworks and across relevant conventions.

Collaborative approaches

In 2015–2016, collaboration between the Mine Ban Treaty and relevant disarmament conventions was strengthened. The Chair of the Mine Ban Treaty’s Committee on Victim Assistance told Convention on Cluster Munitions States Parties that it “would be pleased to work with Coordinators on Victim Assistance under [the] Convention on Cluster Munitions to bridge the gap between the two conventions by exchanging information and updating work plans with each other.”[55]

In February 2016, the Mine Ban Treaty’s Committee on Victim Assistance held a meeting with the Victim Assistance Coordinators of the Convention on Cluster Munitions and Protocol V of the Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW) to share information and to strengthen collaboration. In May 2016, the Convention on Cluster Munitions Coordinators on Victim Assistance and Coordinators on Cooperation and Assistance invited Mine Ban Treaty Victim Assistance Coordinators and States Parties to participate in the development of guidance for states by states on an “integrated approach to victim assistance,” being undertaken with technical support from Handicap International.[56]

Further reflecting the improving orientation toward rights-based assistance, in 2015 the ICRC, for the first time, issued a Special Appeal on Disability and Mine Action. Whereas previously related ICRC special appeals had particularly focused on preventative activities in mine action, the appeal for 2016 acknowledges the increased international attention on issues of disability inclusion attributable to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). It draws on the ICRC’s adjusted operational framework orientation of 2014 that is specifically inclusive of the needs of all persons with disabilities.[57]

Also, in 2016, the UN issued an expanded policy on victim assistance in mine action.[58] This policy, which “intends to generate a renewed impetus and commitment from the United Nations in support of mine and ERW victims,” draws on the expertise of UN agencies and programs, the ICBL, NGOs, mine action program managers, experts, and donor countries.[59]

In September 2015, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were agreed at a UN summit. The SDGs are a set of 17 goals with targets and indicators that all UN member states are expected to use to frame policies and stimulate action for positive change over the period from 2015 to 2030. They are designed to address the economic, social, and environmental dimensions of sustainable development. With an emphasis on poverty reduction, equality, and inclusion, the SDGs also recognize the need for the “achievement of durable peace and sustainable development in countries in conflict and post-conflict situations.” Therefore, the SDGs are generally complementary to the abovementioned aims of the CRPD, the Mine Ban Treaty, and the Convention on Cluster Munitions, and offer opportunities for bridging between the relevant frameworks as outlined by the Maputo Action Plan.

Persons with disabilities are referred to directly in several goals: education (Goal 4), employment (Goal 8), reducing inequality (Goal 10), and accessibility of human settlements (Goal 11), in addition to including persons with disabilities in data collection and monitoring (Goal 17). Pragmatically, victim assistance is fully compatible with the SDGs and thus scarce resources for victim assistance should be maintained and can be considered an effective contribution to the achievement of the SDGs.

Much remains to be done, of course. Speaking at a special high-level victim assistance session during the Mine Ban Treaty Fourteenth Meeting of States Parties in November 2015, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities pointed out potential future challenges to the success of development goals:

The Sustainable Development Goals offer a great opportunity for all, including for persons with disabilities. However, the limited capacity to implement and measure the level of impact of the SDGs is a risk that must be addressed in order to avoid another failure of the development agenda in relation to persons with disabilities.[60]

Implementation of the Maputo Action Plan by States Parties

The Maputo Action Plan provides a framework that allows States Parties to qualitatively assess progress in victim assistance, which they can attribute to the relevant actions that they take, even in the absence of existing measurable baselines. It calls for activities addressing the specific needs of victims while also emphasizing the necessity of simultaneously integrating victim assistance into other frameworks by incorporating relevant actions into the appropriate sectors, including disability, health, social welfare, education, employment, development, and poverty reduction.[61] States Parties commit to addressing victim assistance objectives “with the same precision and intensity as for other aims of the Convention.”[62]

The actions of the Maputo Action Plan can be summarized as follows:

- Assess the needs; evaluate the availability and gaps in services; support efforts to make referrals to existing services.

- Enhance plans, policies, and legal frameworks.

- Ensure the inclusion and full and active participation of mine victims and their representative organizations in all matters that affect them; enhance capacity.

- Increase the availability of and accessibility to services, opportunities, and social protection measures; strengthen local capacities and enhance coordination.

- Address the needs and guarantee rights in an age- and gender-sensitive manner.

- Communicate time-bound and measurable objectives annually.

- Report on measurable improvements in advance of the next review conference.

The Maputo Action Plan also affirms the need for States Parties to continue carrying out the actions of the previous Cartagena Action Plan, which sought to make assistance available, affordable, accessible, and sustainable.[63]

Assessing the needs

States Parties should assess needs for victim assistance—including through sex- and age-disaggregated data—and gauge the availability of services required, including though barrier assessments. They should also use this assessment activity as an opportunity to make referrals to existing services.[64] No nationwide victim or survivor needs assessments were reported in 2015.

Some specific survey activities and assessments of needs of survivors or victims in 2015–2016 included the following. In Albania, an assessment of socio-economic and medical needs of marginalized ERW survivors carried out during 2013–2016 was completed. In Cambodia, village-level quality of life assessments for survivors and other persons with disabilities continued. In Colombia, data collection on the needs of mine/ERW victims was ongoing, and in June 2015, the deadline expired for the registration of persons victimized between 1 January 1985 and 10 June 2011 into the national database on conflict victims who can receive state assistance. Croatia continued to make progress in the development of a unified database on casualties of mine/ERW survivors and their families. In Serbia, the ministry responsible for victim assistance worked with other government institutions to improve coordination on data and needs assessment. In Darfur, Sudan, work continued with disabled peoples’ organizations (DPOs) to identify, through individual case studies, the needs of landmine and ERW survivors. In Tajikistan, ICRC needs assessment continued and information was entered into the national database to be shared with relevant stakeholders. Thailand reported that data collection on mine/ERW survivors was relatively advanced and that survivors are included in disability assessments. In Yemen, more mine/ERW victims were registered with the mine action center through ongoing survey conducted jointly with the national survivor association.

Enhancing plans, policies, and legal frameworks

Coordination

States Parties committed to enhancing coordination activities in order to increase the availability and accessibility of services that are relevant to mine victims.[65] In 2015 and into 2016, 21 of the 31 States Parties had active victim assistance coordination mechanisms or disability coordination mechanisms that considered the issues relating to the needs of mine/ERW survivors.[66] (See infographic at the end of this chapter.)

Among the States Parties with active victim assistance coordination in 2015, almost all the national coordination mechanisms were reported to have either collaborated with, or been included as part of, an active disability coordination mechanism.

In the following 13 States Parties, the national bodies in charge of coordinating victim assistance[67] collaborated with those in charge of coordinating disability rights: Afghanistan, Albania, Angola, Burundi, Chad, Colombia, Croatia, El Salvador, Jordan, Peru, Serbia, Sudan, and Thailand. Such coordination mechanisms were also in place in Algeria and Yemen, but they did not hold any meetings in 2015. Ad hoc meetings were held in BiH. Victim assistance coordination continued in Yei county in South Sudan.

Victim assistance was included in mechanisms for coordination of disability issues, without a separate victim assistance coordination body, in five States Parties: Cambodia, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Nicaragua, and Tajikistan. In DRC and Uganda, the disability mechanisms with responsibility for victim assistance coordination did not meet in 2015.

No active coordination mechanism was reported in Eritrea, Guinea-Bissau, Iraq, Nicaragua, Senegal, Somalia, Turkey, Uganda, or Zimbabwe. Turkey had a National Mine Center with a mandate for coordinating victim assistance that existed from January 2015 until mid-2016, but no activities or collaboration with national disability coordination mechanisms were reported.

Plans and objectives

Actions #13 and #14 of the Maputo Action Plan call on States Parties to have time-bound and measurable objectives to implement national policies and plans that will tangibly contribute to the main goals of victim assistance.

In 2015, of the 31 States Parties with significant numbers of survivors, 16 had current and ongoing plans with objectives that address the needs and promote the rights of mine survivors.[68] Plans for Burundi, Croatia, Senegal, and Uganda expired in 2014 without yet having been renewed. A new National Disability Action Plan for Afghanistan remained pending, but was under development. Algeria had developed a victim assistance plan that was pending official approval in 2016. A revision of the victim assistance plan for Chad, which was extended due to a lack of resources and inactivity, was slated to take place in 2016. In Yemen, implementation of the plan remained on hold due to armed conflict.

Actions responding to some needs of mine survivors have been incorporated into the national disability plans in Cambodia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Serbia, and South Sudan. These states did not have a distinct victim assistance plan.

Colombia, Mozambique, Peru, and Tajikistan had both a national victim assistance plan and disability plans and policies that take into account the needs and rights of mine/ERW survivors.[69] Mozambique adopted its victim assistance strategy, as an addition to its disability strategy, in December 2015. In August 2016, a Workshop for Development of National Victim Assistance Strategic Framework was held in Sudan.

Availability of and accessibility to services

Action #15 of the Maputo Action Plan commits States Parties to “increase availability of and accessibility to appropriate comprehensive rehabilitation services, economic inclusion opportunities and social protection measures…including expanding quality services in rural and remote areas and paying particular attention to vulnerable groups.”

Updates on the availability and accessibility of comprehensive rehabilitation for mine/ERW survivors and other persons with disabilities are included in separate reporting produced by the Monitor.[70] This Monitor reporting on access, inclusion, and rights in 33 countries, organized under the sub-thematic title “Equal Basis,”[71] presents progress in the relevant States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty and Convention on Cluster Munitions[72] in the context of the CRPD.

The Monitor website includes detailed country profiles examining progress in victim assistance in some 70 countries, including both States Parties and states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty and the Convention on Cluster Munitions.[73] A collection of thematic overviews, briefing papers, factsheets, and infographics related to victim assistance produced since 1999, as well as the latest key country profiles, is available through the victim assistance portal on the Monitor website.[74]

Communicating objectives and reporting improvements

According to Action #13 of the Maputo Action Plan, victim objectives should be updated, their implementation monitored, and progress reported annually. Each year, “enhancements” to plans, policies, legal frameworks, and budgets for the implementation of those plans, policies, and legal frameworks should also be reported. More precise reporting is called for, and in 2016, a representative of Colombia, a member of the Mine Ban Treaty Victim Assistance Committee, noted that states need to listen to needs and show progress, but not exaggerate their victim assistance accomplishments.[75]

As in the previous year, more than half of the most-affected 31 States Parties included some information on victim assistance activities in their Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 reports covering calendar year 2015.[76] States Parties that reported on plans, policies, or legislative frameworks in Form J of their Article 7 reporting for 2015, primarily addressed existing plans with a few references to enhancements or adaptations made to plans or policies.

However, time-bound and measurable objectives and progress toward goals went almost unreported. Only Thailand reported directly on national time-bound and measurable objectives. Few States Parties reported on the challenges to implementation of victim assistance in their countries as suggested by the 2015 Mine Ban Treaty guide to reporting; Sudan and Zimbabwe were notable exceptions where information on challenges was noted. States Parties rarely shared good practices in their reports. Key principles of victim assistance such as non-discrimination, age and gender sensitivity, accessibility, and inclusion were seldom included in the reporting.

Mine Ban Treaty States Parties are encouraged to use Form J of the Article 7 reporting format “in particular to report on assistance provided for the care and rehabilitation, and social and economic reintegration, of mine victims.”[77] There is no detailed or specific format for reporting on victim assistance under the Mine Ban Treaty, however suggestions and guidelines have been presented over time.[78]

Monitor research has shown that annual updates in reporting are most useful for assessment purposes when they clearly indicate when changes occurred against specific key indicators or concrete points of progress.

In 2015, a guide for reporting under the Mine Ban Treaty suggested that States Parties that are also parties to the CRPD could “draw from efforts that have been undertaken in the context of fulfilling CRPD reporting requirements and from the conclusions and recommendations made on these reports by the United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.”[79] However, due to challenges in CRPD reporting—owing to its level of complexity, backlog in reviewing, and relative infrequency—the CRPD has been insufficient thus far to replace annual Mine Ban Treaty reporting on progress and challenges to addressing the needs of victims.

Regular reporting by States Parties on implementation of the CRPD is required by Article 35 of that convention. Reporting on the CRPD is less frequent that Mine Ban Treaty reporting. The Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities examines each report and provides suggestions and recommendations to the State Party. However, despite the adoption of a simplified reporting procedure in 2013, in 2015 the committee actually registered an increase in the extensive backlog of State Party reports pending review.[80]

Given the overlap in context and objectives between the CRPD and victim assistance, Mine Ban Treaty reporting offers an opportunity for states to specifically address progress against recommendations and concerns raised in the CRPD framework. Mine Ban Treaty States Parties have not taken that opportunity. Monitor reporting on victim assistance does, however, draw specifically from states’ CRPD reporting, alternative reporting, and recommendations as they become available.

In its initial CRPD report submitted in 2015, Algeria made a short reference to landmine survivors. Previously, BiH, Colombia, Croatia, and Uganda submitted reports on their implementation of the CRPD (Article 35) that had references to landmine victims, mostly short notes or references to CRPD Article 11 on humanitarian emergencies and conflict.

Full and active participation

Action #16 of the Maputo Action Plan commits States Parties to ensure the “full and active participation of mine victims and their representative organizations in all matters that affect them.”

During the reporting period, among the States Parties with victim assistance coordination activities during 2015, all had some form of survivor participation or consultation; sometimes directly, or through survivors’ representative organizations or DPOs. Nonetheless there remains a long way to go for survivors to be effectively included in coordination roles in a way that ensures that their input is listened to, understood, and acted upon. In Ethiopia, survivors were not directly involved in coordination meetings, but were consulted in the development of relevant plans and strategies. In Tajikistan, survivors attended a range of relevant meetings.

Few States Parties endeavored to demonstrate that they are doing their utmost to enhance the capacity of survivors for their effective participation, or to specify the methods that they are using to build that capacity. Cambodia, Tajikistan, and Thailand reported activities in regard to building such capacity.

Mine/ERW survivors also continued to participate actively in Mine Ban Treaty and other disarmament and disability rights coordination and campaigning, as well as in matters of peacemaking and peace-building in many countries, including in Albania, Afghanistan, Cambodia, Colombia, Croatia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Iraq, Serbia, Senegal, Thailand, and Uganda.

In the majority of the 31 States Parties, survivors continued to be involved in implementing many aspects of victim assistance, including physical rehabilitation, peer support and referral, income-generating projects, and needs assessment data collection.[81] However, the extent of these essential community services was severely reduced due to cuts in the small amounts of funding that had previously been available for these activities (see section on funding below).

Gender and age considerations

The Maputo Action Plan speaks of “the imperative to address the needs and guarantee the rights of mine victims, in an age- and gender-sensitive manner.”[82] While men and boys are the majority of reported casualties, women and girls may be disproportionally disadvantaged as a result of mine/ERW incidents and suffer multiple forms of discrimination as survivors. To guide a rights-based approach to victim assistance for women and girls, States Parties can apply the principles of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW).[83] Implementation of CEDAW by States Parties to that convention should ensure the rights of women and girls and protect them from discrimination and exploitation.[84]

Some States Parties have begun to address gender issues, often with assistance from the Gender and Mine Action Programme (GMAP). GMAP assessments of national mine action programs always include victim assistance as a component. Since 2013, GMAP has assessed the following Mine Ban Treaty States Parties’ programs: Afghanistan, DRC, Mali, Mozambique, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan (Darfur), and Tajikistan. The DRC assessment was carried out in 2015.[85] The national victim assistance working group in Serbia also proposed the integration of victim assistance for women into the National Action Plan for UN Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security.

Age considerations

Child survivors have specific and additional needs in all aspects of assistance. During the reporting period, some progress in addressing the specific needs of child survivors was reported in some domains of assistance, particularly psychosocial support and education. In this regard, the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) is particularly relevant to the implementation of victim assistance with a rights-based approach. The annually updated Monitor fact sheet on the Impact of Mines/ERW on Children contains more details on issues pertaining to children, youth, and adolescents.[86]

Special issues of concern: fragile states, conflict, and humanitarian emergencies

States Parties facing conflict and deteriorating security situations often report interruption of victim assistance activities and services, and a lack of accessibility to existing services.[87] At least 15 (about half) of the Mine Ban Treaty States Parties with significant numbers of landmine victims[88] are listed in the 2015 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report, “States of Fragility.” States with fragile situations may require more capacity or support in order to compile and submit updates on victim assistance. Further to the difficulties faced in fragile states, conflict situations and natural disasters also influence the prevalence of disability, both by creating impairments and by creating barriers to access in the physical environment.[89]

Several activities were underway to raise awareness of, or improve, responses to the needs and rights of persons with disabilities in armed conflicts and fragile situations that could potentially benefit mine survivors and their communities.

A special session of the World Humanitarian Summit in Turkey in May 2016 on Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities into Humanitarian Action resulted in the adoption of a charter that is open for endorsement by states and NGOs alike.[90] The session, chaired by the Special Rapporteur on Disabilities, saw relevant interventions by UNMAS, Handicap International, and several others. No mine/ERW survivors were reported to have participated in the session.

A 2015 thematic study of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) notes that under the Maputo Action Plan, Mine Ban Treaty States Parties committed to integrate landmine victims with disabilities into the broader legal frameworks related to the rights of persons with disabilities, thus reflecting “a more updated understanding of the issue.”[91] The issues related to the rights of persons with disabilities in situations of conflict and humanitarian emergencies were further discussed and considered by the Human Rights Council in March 2016.[92]

Overall, these states likely face challenging barriers to fulfilling their commitments under the Maputo Action Plan and to reporting progress and gaps in assistance. With specific international support and well-directed cooperation, as well as increased national focus at all levels of governance, States Parties in fragile situations would be better able to address victim assistance commitments.[93]

Cooperation, support, and funding for victim assistance

Action #20 of the Maputo Action Plan calls on States Parties to “effectively use all possible avenues to support States Parties seeking to receive assistance.” Concerning victim assistance, this includes “providing targeted assistance and supporting broader efforts to enhance frameworks.” In 2016, Australia summarized this twin-track approach—also referred to as an integrated approach—to victim assistance with regard to donors across conventions as follows:

…development assistance needs to include specific programs for survivors, which are also accessible to other people with disabilities. Our development assistance also needs to include programs to ensure the needs of survivors as well as all other people with disabilities are addressed in national level policies and programs.[94]

Even with the efforts of states to find pathways for suitable sustainable resource allocation, in 2015 inadequate funding and resources in many states contributed to a reduction in activities to deliver most direct assistance and services to survivors, including those of international organizations, national and international NGOs, and DPOs. Thus, in May 2016, the ICBL expressed concern that in many countries local-level resources available for victim assistance are “reaching the point of catastrophic deficiency.” At the same time the UN stated that “victim assistance is a mine action pillar that remains grossly underfunded.”[95]

Cases from States Parties with significant numbers of survivors that experienced severe funding shortages for victim assistance, thus disrupting the implementation of activities or otherwise impeding progress in improving the quality of life of survivors in 2015–2016, can be seen in the following examples:

- In Angola, the economic crisis due to reduced oil prices slashed funds available for government-supported assistance and resulted in a near shutdown of most victim assistance programs. The government refurbished some rehabilitation and orthopedic clinics, but failed to provide the supplies and materials needed to deliver services.

- In BiH, a lack of resources continued to erode victim assistance efforts by NGOs as donor funding declined. After more than 18 years of continuous operation, the NGO Landmine Survivors Initiatives (once a branch office of the United States-based NGO Landmine Survivors Network/Survivor Corps) closed down permanently.[96]

- In Burundi, there was a reduction in the number of victim assistance service providers due to lack of funding in 2015.[97] Implementation of the National Victim Assistance Action Plan remained largely on hold due to deficient resources.[98]

- In Chad, the timeframe of the National Plan of Action on Victim Assistance 2012–2014 had been extended to 2017 because of a lack of resources for its implementation. However, in 2015, further budget cuts did not allow for implementation of the plan.

- In DRC, international funding for victim assistance provided through UNMAS and other donors remained worryingly low in 2015.[99] This led to a stagnation in the availability of services, the number of actors, and geographical coverage of assistance.[100]

- In Croatia, there was an overall decrease in the number of people that could get assistance due to the “omnipresent lack of financial resources.”[101] The government reduced overall funding for programs for persons with disabilities as part of budget cuts.[102] Austerity measures had already reduced the previously achieved standard supply of orthopedic devices.[103]

- In Ethiopia, a major rehabilitation provider reported a significant decrease in victim assistance services and limited the range of mobile outreach teams due to a reduction of funds.[104]

- Iraq suffers from a financial crisis, while the focus of donors and international NGOs is on the massive needs of internally displaced persons. This has diverted financial support away from victim assistance and minimized the scale of service provision to mine/ERW survivors across the country.[105]

- In Mozambique, insufficient financial resources was one of the main challenges to implementation of victim assistance activities.[106] Donors were reported to be losing interest in victim assistance as a result of the completion of landmine clearance in the country.[107]

- In Tajikistan, the main obstacle to the implementation of victim assistance- and disability-related projects and programs was the lack of sustainable funding from both the government and donors.[108]

- In Uganda, a significant reduction in the overall level of survivor participation in 2015 was attributed to a lack of funding for victim assistance programs in general.[109]

Similarly, a lack of funding was reported to have reduced services in Afghanistan, El Salvador, and Yemen—States Parties also experiencing conflict or security concerns. In Somalia, South Sudan, and Sudan, resources as well as the impact of conflict were also impediments to the provision of assistance.

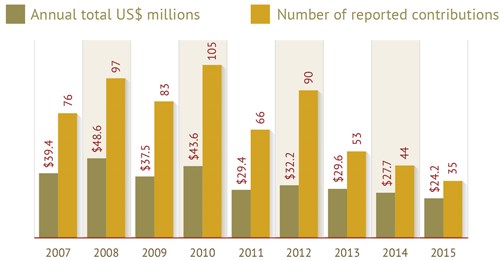

Analysis of victim assistance funding in detailed data available since 2007 shows a decline in total funding over time. The number of donor-reported contributions[110] made annually also decreased in real terms and as compared to the total annual earmarked funding. Of the total annual funding earmarked for victim assistance, generally some US$10–13 million per year was allocated to the ICRC and $2–5 million to Handicap International; these figures remained fairly constant. Funding to a diversity of other organizations and projects, particularly to survivors’ representative organizations, decreased significantly.

International donor funding for victim assistance 2007–2015

Despite an earlier “prediction that in the coming years we will see a downward trend in funds identified as dedicated to assisting victims…but that more and more states, including donors…will strive to ensure that their development cooperation is inclusive of all persons with disabilities,”[111] to date funding through other frameworks such as disability-inclusive development has not been demonstrated to have replaced victim assistance-earmarked funding nor general funding shortages.

There may be a general misconception that victim assistance-earmarked funding necessarily assists only or even mostly mine/ERW victims. Rather, victim assistance contributions are directed at projects and sectors that include mine victims amongst beneficiaries and are most often labelled as such because they are among those financial contributions designated through or authorized by the government aid humanitarian agencies that also allocate mine action funding. Consequently, earmarked victim assistance funding is equally important to survivors and indirect victims as well as other persons with similar needs. The ICBL-CMC has recommended that donors support targeted victim assistance where needed and effective, and fund the implementation of national victim assistance plans, as well as disability action plans and other plans and policies, that have been shown to positively impact victims. Donors can thus dedicate victim assistance funding to fill gaps in service delivery that are needed by mine/ERW victims and ensure access to existing services available to a broader population.[112]

Thailand and Belgium, as co-chairs of the Victim Assistance Standing Committee in 2009—as they were again on the Victim Assistance Committee in 2015—presented a set of guidance recommendations for implementation of victim assistance. What they recommended then, regarding resource mobilization, remains as true today: Addressing the rights and needs of mine victims…

…requires sustained political, financial and material commitments, provided both through national commitments and international, regional and bilateral cooperation and assistance, in accordance with the obligations under Article 6.3. No progress in improving the quality of daily life of mine victims and other persons with disabilities will be possible without adequate resources to implement policies and programmes.[113]

In October 2016, ICBL Ambassador, Landmine Monitor researcher, and landmine survivor Margaret Arach Orech described the dire situation regarding support for victim assistance and the need to resolve it through close consultation with survivors, which is consistent with these Monitor findings. Drawing from her own experience and that of other survivors, she said in a presentation:

Spending on victim assistance has consistently declined in the recent past. Despite the good policies, legal environment and the accompanying strategies for disability issues…the amount of public resources directly allocated for disability programs or for making mainstream programs, whether schools or work places, accessible, is insufficient.

There is considerable discrepancy between what is promised through government policies and what is provided for in the budgets. Generally, limited or lack of funds targeted to specific issues related to persons with disabilities further contribute to the discrimination and marginalization of persons with disabilities, as policies and programs geared towards promoting equal opportunities for vulnerable populations including persons with disabilities are meagerly funded.

Listening and taking into account survivors’ voices is imperative for effective planning of programs or activities that benefit them…Continue to make victim assistance earmarked funds available, and step up efforts to ensure that broader, mainstream policies and programs also respond to the reality faced by survivors and other persons with disabilities.[114]

In Memoriam

On 13 September 2016, a landmine survivor known to friends as Pa (Aunty) Tang passed away. Pa Tang (Taeng Changade) carried on the spirit of the grassroots movement behind the Mine Ban Treaty. Even in hard times she participated in saying what the situation was on the ground, giving her time and energy, and while she physically could, coming to meet campaigners, researchers, and others to give her view and add to the fight against mines and for victims’ rights.

Pa Tang lived in the Sa Kaeo Province of Thailand, at the border with Cambodia. She lost her leg to a landmine while collecting tamarinds to sell at market circa 2003. Her husband left because of her impairment and disability. She lived by herself and supported herself in the years afterwards, until one day she had a terrible accident, lost her balance, and fell into the cooking fire at her home. With severe burns she moved to live with her sister and her children. The family struggled to meet its basic needs. During her last years in her sixties, Pa Tang received some support such as rice and small home adjustments from community-based organizations, with help from the local survivor leader and campaigner.

Pa Tang’s passing reminds us that the promise of victim assistance obligations must be realized within the lifetime of survivors. Survivors are active participants and not statistics.

[1] Casualties from cluster munition remnants are included in the Monitor global mine/ERW casualty data. Casualties occurring during a cluster munition attack are not included in this data; however, they are reported in the annual Cluster Munition Monitor report. For more information on casualties caused by cluster munitions, see ICBL-CMC, Cluster Munition Monitor 2016, the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2016/cluster-munition-monitor-2016/casualties-and-victim-assistance.aspx.

[2] Landmine Monitor 2015 cited a figure of 3,678 casualties for 2014, but the number of casualties for 2014 and past years has been adjusted with newly available data.

[3] Afghanistan, Algeria, Angola, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Burundi, Cambodia, Chad, Chile, Colombia, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Croatia, Cyprus, Ecuador, Egypt, Georgia, India, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Kenya, Kuwait, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Libya, Mali, Morocco, Mozambique, Myanmar, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Pakistan, Palestine, Philippines, Poland, Russia, Senegal, Serbia, Somalia, South Korea, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Syria, Tajikistan, Thailand, Tunisia, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, Vietnam, Yemen, and Zimbabwe, and other areas Abkhazia, Kosovo, Nagorno-Karabakh, Somaliland,and Western Sahara.

[4] Decreases were recorded in Algeria, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, BiH, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, DRC, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea-Bissau, India, Iran, Iraq, Kenya, Lao PDR, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Peru, Russia, Senegal, Serbia, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Tunisia, Vietnam, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, and three other areas, Kosovo, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Somaliland.

[5] Casualties increased in Afghanistan, Angola, Burundi, Chile, Croatia, Cyprus, Ecuador, Egypt, Georgia, Israel, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mali, Morocco, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Palestine, Poland, South Korea, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Tajikistan, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, and Yemen, and two other areas, Abkhazia and Western Sahara. The number in the Philippines and Albania remained the same.

[6] In 1999, the Monitor identified 9,220 mine/ERW casualties.

[7] From 1999 through 2015, 102,970 mine/ERW casualties were recorded, including 26,230 people killed, 72,739 injured, and 4,001 for whom their survival or the deadly outcome of the explosive incident was not known.

[8] A survivor is a person who was injured by mines/ERW and lived.

[9] Security forces can include police as well members of non-state armed groups and militia.

[10] In 2015, the civilian status was not recorded in data for 41% of the reported casualties (2,652). For 2014, in comparison, the number of casualties without reported civilian status was just 3% (118 casualties).

[11] Casualties were identified in the following States Parties in 2015: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, Bangladesh, Belarus, BiH, Cambodia, Chad, Chile, Colombia, DRC, Côte d’Ivoire, Croatia, Cyprus, Djibouti, El Salvador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Greece, Guinea-Bissau, Iraq, Kenya, Kuwait, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Montenegro, Mozambique, Namibia, Nicaragua, Niger, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Rwanda, Senegal, Serbia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Tunisia, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, Yemen, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

[12] Another 22 casualties were identified through Monitor media scanning for calendar year 2015. LibMAC data listed an additional 340 IED casualties that were not included in Monitor records: 66 emplaced IED casualties that did not indicate if the devices were command-detonated or victim-activated; and casualties caused by person-detonated (suicide bombers) and vehicle-borne IEDs (car/truck bombs).

[13] Monitor analysis of casualty data provided by Abdullatif H.M. Abujarida, IMSMA Manager, LibMAC, 23 May 2016; and Monitor media scanning for 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2015.

[14] Hospitals made the identification of the cause of injury. Some casualties recorded as due to ERW may have been casualties of IEDs. Email from Anne Barthes, Handicap International (HI), 26 May 2016.

[15] Casualty data from Regional Emergency Response Office on the Syrian Crisis – HI, 27 May 2016.

[16] Data on injured persons was collected by HI and partners through interviews with displaced people and refugees in Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon between June 2013 and December 2015. The reporting is based on interviews with 68,049 people assessed by HI teams, of which 25,097 were injured: 14,471 in Syria, 7,823 in Jordan, and 2,803 in Lebanon. See, HI factsheet, “Syria: A mutilated future,” Brussels, May 2016, pp. 1–2, bit.ly/HISyriaMay2016; and HI, “New Report: Syrians Maimed and Traumatized by Explosive Weapons,” 20 June 2016, bit.ly/HISyriaJune2016.

[17] The SNHR also documented a number of people injured by cluster munitions when that information was available. SNHR, “Four Years Harvest: The Use of Cluster Ammunition…That is Still Going,” 30 March 2015, http://sn4hr.org/blog/2015/03/30/5346/; and casualty data sent by email from Fadel Abdul Ghani, Director, SNHR, 8 June 2016.

[18] The 812 mine/ERW survivors were among of 28,565 weapon-wounded persons in total admitted to ICRC-supported healthcare facilities in 2015. ICRC, “Annual Report 2015,” Geneva, 2016, p. 526; and email from Rima Kamal, ICRC Yemen, 7 June 2016.

[19] ICRC, “Annual Report 2015,” Geneva, 2016, p. 526; and email from Rima Kamal, ICRC Yemen, 7 June 2016.

[20] ICRC, “Annual Report 2014,” Geneva, May 2015, p. 515.

[21] For Afghanistan UNAMA categorizes IEDs by the basic method used to initiate detonation, including victim-activated IEDs, remote control/radio/command-operated IEDs, and suicide IEDs. The most common victim-activated IEDs in Afghanistan are pressure plate IEDs, which are improvised landmines.

[22] According to a UN Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI) report, all types of IEDs collectively were reported to have caused 7,086 civilian casualties (1,717 killed and 5,369 injured) in Iraq during the period 1 May to 31 October 2015, but none of these casualties are included in Monitor reporting because they are not disaggregated by IED type. See UNAMAI monthly reports on protection of civilians; and UNAMI/OCHA, “Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq: 1 May – 31 October 2015,” January 2016, bit.ly/UNAMIMayOct2015. iMMAP (an independent organization once part of the former Vietnam Veterans of America Foundation’s Information Management and Mine Action Programs) reported that IEDs killed 7,525 and injured 12,751 from January 2014 to January 2016, but victim-activated IEDs were not disaggregated in the data. Action on Armed Violence (AOAV) recorded 1,190 IED casualties in Iraq for 2015; 23 military and security forces and eight civilian casualties were caused by booby-traps but these were not marked specifically as victim-activated IED incidents. Another two were killed by a device that was recorded as victim-activated, while laying the IED, and were therefore not included in the Monitor total. The Monitor has requested disaggregated data on IED casualties from relevant UN agencies, mine action centers, and iMMAP.

[23] Email from Riyad Nasir, Community Liaison Department, Directorate of Mine Action, 26 June 2016.

[24] The Monitor tracks the age, sex, civilian status, and deminer status of mine/ERW casualties to the extent that data is available and disaggregated.

[25] Child casualties are defined as all casualties where the victim is less than 18-years of age at the time of the incident.

[26] Child casualties were recorded in Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, Azerbaijan, Burundi, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, DRC, Egypt, India, Iran, Iraq, Kenya, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Libya, Mali, Morocco, Myanmar, Namibia, Pakistan, Palestine, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Tajikistan, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, Yemen, and Zimbabwe, and two other areas, Somaliland and Western Sahara.

[27] There were 829 boys and 180 girls recorded as casualties in 2015; the sex of 63 child casualties was not recorded.

[28] For 2,435 casualties the sex was not known.

[29] In 2015, casualties among deminers occurred in Afghanistan, Cambodia, Colombia, Croatia, Ecuador, Iran, Iraq, Tajikistan, Yemen, and Zimbabwe.

[30] There were 1,675 casualties among deminers from 1999 through 2015. Since 1999, the annual number of demining casualties identified has fluctuated greatly, making it difficult to discern trends. Most major fluctuations have been related to the exceptional availability or unavailability of deminer casualty data from a particular country in any given year and therefore cannot be correlated to substantive changes in operating procedures, international demining standards, or demining equipment.

[31] The explosive device type was not known for 1,352 casualties (21% of the total) in 2015, and for 279 casualties (8%) in 2014: see analysis in this section. The number of recorded cluster submunition casualties (76, including two in South Sudan not yet counted when Cluster Munition Monitor 2016 was published) is likely much lower than the actual number because ERW data often does not differentiate by weapon type. See, ICBL-CMC, Cluster Munition Monitor 2016, the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2016/cluster-munition-monitor-2016/casualties-and-victim-assistance.aspx.

[32] Afghanistan, Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Mali, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, Russia, Syria, Thailand, Tunisia, and Ukraine.

[33] All antipersonnel mine casualties in 2015 in Colombia were reported to be improvised/homemade.

[34] From media reporting it was often not possible to distinguish between tripwire mines and improvised antipersonnel mines made from a tripwire and hand grenade, which were prolifically causing casualties. In many cases, the Monitor recorded these casualties as caused by antipersonnel landmines.

[35] In 2015, unspecified mine casualties were recorded in Algeria, Egypt, Iran, Lebanon, Libya, Mali, Niger, Syria, Thailand, Ukraine, and Yemen.

[36] In 2015, casualties from antivehicle mines were identified in the following states: Afghanistan, Angola, Cambodia, Cyprus, Egypt, Georgia, Lebanon, Mali, Morocco, Pakistan, South Sudan, Syria, Thailand, Ukraine, and Yemen,and three other areas, Abkhazia, Somaliland, and Western Sahara.

[37] The Monitor shares, cross-references, and compares data with the Geneva Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) and Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) Anti-vehicle mines (AVM) project. That project recorded 598 casualties from both confirmed (388) and suspected (210) antivehicle mines in 25 countries in 2015. While much of the data matches with the Monitor data, each of the methodologies used to enter data differ, resulting in the discrepancies in annual casualties reported. For example, Monitor data does not include casualties that occur while engaged in laying mines. Monitor reporting does include politically disputed geographic “other areas” in reporting, and tends to use the definitions employed in original whole data sets when possible. Casualty data provided by email from Ursign Hofmann, Policy Advisor, GICHD, 11 July 2016. See also, GICHD-SIPRI, “Anti-Vehicle Mine Incidents Map,” undated, www.gichd.org/avm - ch18738.

[38] Those also made up the vast majority of the 988 casualties recorded for Yemen in 2015.

[39] Unknown device casualties were recorded in Egypt, Iran, Lebanon, Libya, Mali, Myanmar, Palestine, Philippines, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Syria, Thailand, Ukraine, and Yemen, and one other area, Western Sahara.

[40] In 2015, casualties from ERW were identified in the following states: Afghanistan, Albania, Angola, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Burundi, Cambodia, Colombia, DRC, Egypt, India, Iran, Iraq, Kenya, Lao PDR, Libya, Mali, Mozambique, Myanmar, Namibia, Pakistan, Palestine, Poland, Russia, Serbia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tajikistan, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, and Vietnam, and four other areas, Kosovo, Nagorno-Karabakh, Somaliland, and Western Sahara. In addition to other types of ERW, casualties of unexploded submunitions were identified in Afghanistan, Cambodia, Chad, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Syria, Ukraine, and Yemen, and two other areas, Nagorno-Karabakh and Western Sahara. For more information on casualties caused by unexploded submunitions and the annual increase in those casualties recorded for the year 2015, see ICBL-CMC, Cluster Munition Monitor 2016, the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2016/cluster-munition-monitor-2016/casualties-and-victim-assistance.aspx.

[41] Of the total ERW casualties in 2015, 326 were adults and 970 were without a reported age group.

[42] Mine Ban Treaty, Article 6.3, www.apminebanconvention.org/overview-and-convention-text/.

[43] A “survivor” is a person who was injured by mines/ERW and lived.

[44] See, “Nairobi Action Plan 2005–2009,” www.icbl.org/media/933290/Nairobi-Action-Plan-2005.pdf.

[45] “Maputo Action Plan,” Maputo, 27 June 2014, www.maputoreviewconference.org/fileadmin/APMBC-RC3/3RC-Maputo-action-plan-adopted-27Jun2014.pdf.

[46] MAPUTO +15, Declaration of Mine Ban Treaty States Parties, adopted 27 June 2014.

[47] Convention on Cluster Munitions Coordinators of the Working Group on Victim Assistance and the Coordinators of the Working Group on Cooperation and Assistance, “Guidance on an integrated approach to victim assistance,” (CCM/MSP/2016/WP.2) 11 July 2016, bit.ly/IntegratedApproachGuidance2016.

[48] Such as national laws, policies, and plans on issues such as health, disability, education, labor, transportation, social welfare, rural development, poverty reduction, and overseas development assistance.

[49] Convention on Cluster Munitions Coordinators of the Working Group on Victim Assistance and the Coordinators of the Working Group on Cooperation and Assistance, “Guidance on an integrated approach to victim assistance,” (CCM/MSP/2016/WP.2) 11 July 2016, bit.ly/IntegratedApproachGuidance2016. See also, statement of Thailand, Convention on Cluster Munitions Sixth Meeting of States Parties, Geneva, 6 September 2016, in which Thailand welcomes the Workshop on an Integrated Approach to Victim Assistance; and Convention on Cluster Munitions Implementation Support Unit (ISU), “Workshop on an Integrated Approach to Victim Assistance,” (including workshop documents) 27 May 2016, www.clusterconvention.org/2016/05/27/workshop-on-an-integrated-approach-to-victim-assistance.

[50] See, “Assisting the Victims: Recommendations on Implementing the Cartagena Action Plan 2010–2014,” Presented to the Mine Ban Treaty Second Review Conference by Co-Chairs of the Standing Committee on Victim Assistance and Socio-Economic Reintegration, Belgium and Thailand, Cartagena, Colombia, 30 November 2009, bit.ly/CartegenaPlanVA; and “Parallel Programme – Victim Assistance,” which contains links to information from such programm between 2007 and 2012, victim-assistance.org/about/victim-assistance-resources/pp.

[51] This corresponds with Actions #12 to #18 of the Maputo Action Plan. The Monitor reports on the following 31 Mine Ban Treaty States Parties in which there are significant numbers of survivors: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, BiH, Burundi, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, DRC, Croatia, El Salvador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau, Iraq, Jordan, Mozambique, Nicaragua, Peru, Senegal, Serbia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda, Yemen, and Zimbabwe. This list includes 29 States Parties that have indicated that they have significant numbers of survivors for which they must provide care, as well as Algeria and Turkey, which have both reported hundreds or thousands of survivors in their official landmine clearance deadline (Mine Ban Treaty Article 5) extension request submissions. Algeria, Mine Ban Treaty Revised Article 5 Extension Request, 31 March 2011, bit.ly/AlgeriaExtension2011; and Turkey, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 Extension Request, 28 March 2013, bit.ly/TurkeyExtension2013.

[52] Statement of Thailand, Convention on Cluster Munitions Sixth Meeting of States Parties, Geneva, 6 September 2016.

[53] In addition, States Parties Mali and Ukraine, both of which have had hundreds of mine/ERW casualties in the past two years, may be considered to have significant numbers of survivors with great needs for assistance that remain unreported.

[54] “Decisions on the Convention’s Machinery and Meetings,” Maputo, 27 June 2014, p. 5, www.maputoreviewconference.org/fileadmin/APMBC-RC3/3RC-Decisions-Machinery-27Jun2014.pdf.

[55] Statement of Thailand, Convention on Cluster Munitions Sixth Meeting of States Parties, Geneva, 6 September 2016.

[56] Statement of Australia (Speaking as Coordinator on Victim Assistance for the Convention on Cluster Munitions), Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Meetings, Geneva, 19 May 2016.

[57] ICRC, “Special Appeal 2016: Disability and Mine Action,” Geneva, December 2015, www.icrc.org/sites/default/files/topic/file_plus_list/disability_mine2016_rex2015_651_final.pdf.

[58] “The United Nations Policy on Victim Assistance in Mine Action (2016 Update),” bit.ly/UNMineActionVA2016.

[59] UNMAS, “Issues: Victim Assistance,” www.mineaction.org/issues/victimassistance.

[60] Statement by Catalina Devandas Aguilar, Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Mine Ban Treaty Fourteenth Meeting of States Parties, 30 November 2015.

[61] Actions #12 to #18 of the Maputo Action Plan.

[62] “Maputo Action Plan,” Maputo, 27 June 2014, p. 3.

[63] “Cartagena Action Plan 2010–2014: Ending the Suffering Caused by Anti-Personnel Mines,” Cartagena, 11 December 2009 (hereafter referred to as the “Cartagena Action Plan”), www.cartagenasummit.org/fileadmin/APMBC-RC2/2RC-ActionPlanFINAL-UNOFFICIAL-11Dec2009.pdf.

[64] According to Action #12 of the Maputo Action Plan.

[65] According to the ongoing Cartagena Action Plan victim assistance commitments and supported by Action#15 of the Maputo Action Plan.

[66] The states with coordination mechanisms were: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, BiH, Burundi, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, Croatia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Jordan, Mozambique, Peru, Serbia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, and Yemen (largely inactive due to conflict).

[67] Including coordination bodies for war victims more broadly.

[68] Albania, Angola, BiH, Burundi, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau, Jordan, Mozambique, Peru, Tajikistan, Thailand, and Yemen. States with no plan or expired plans: Afghanistan, DRC, Croatia, Eritrea, Iraq, Nicaragua, Senegal, Serbia, Somalia, Sudan, Turkey, Uganda, and Zimbabwe. No plans were reported for the remaining States Parties.

[69] In Colombia and El Salvador, planning of mine/ERW victim assistance was also integrated into efforts to address the needs of armed conflict victims more generally.

[70] See also, ICBL-CMC, “Equal Basis 2015: Inclusion and Rights in 33 Countries,” 2 December 2015, www.the-monitor.org/media/2155496/Equal-Basis-2015.pdf; and ICBL-CMC, “Equal Basis 2014: Access and Rights in 33 Countries,” 3 December 2014, www.icbl.org/en-gb/news-and-events/news/2014/equal-basis-2014-access-and-rights-in-33-countries.aspx.

[71] A core principle of the CRPD, the term “on equal basis with others” is used 31 times throughout the CRPD text. However, no definition of the term is included.

[72] The 31 Mine Ban Treaty States Parties detailed here, plus Lao PDR and Lebanon that are States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions.

[73] Country profiles are available on the Monitor website, www.the-monitor.org/cp. Findings specific to victim assistance in states and other areas with victims of cluster munitions are available through Landmine Monitor 2016’s companion publication; ICBL-CMC, Cluster Munition Monitor 2016, the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2016/cluster-munition-monitor-2016/casualties-and-victim-assistance.aspx.

[74] See, the Monitor, “Victim Assistance Resources,” the-monitor.org/en-gb/our-research/victim-assistance.aspx

[75] Ambassador Beatriz Londoño Soto, Mine Ban Treaty Committee on Victim Assistance, “Creating understanding and awareness of victim assistance actions in accordance with the Maputo Action Plan at all levels,” side event panel, Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Meetings, Geneva, 19 May 2016.

[76] The States Parties that provided some updates on victim assistance were: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, BiH, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, Croatia, El Salvador, Iraq, Jordan, Nicaragua, Peru, Senegal, South Sudan, Sudan, Thailand, Turkey, and Zimbabwe. As of 15 October 2016, 12 of the most affected 31 States Parties had not submitted Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 reports for calendar year 2015: Angola, Burundi, DRC, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, Serbia, Somalia, Tajikistan, Uganda, and Yemen.

[77] Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report, Form J, Reporting Format.

[78] See, ICBL Working Group on Victim Assistance (Prepared for the Standing Committee on Victim Assistance, Socio-economic Reintegration and Mine Awareness), “Draft Suggestion for Use of Form J to Report on Victim Assistance,” December 2000, bit.ly/FormJSuggestions2000; and see the more recent Mine Ban Treaty, “Guide To Reporting,” October 2015, bit.ly/2MBTReportingGuide2015.

[79] Mine Ban Treaty, “Guide to Reporting,” para. G.38, October 2015 (adopted in December 2015 at the Fourteenth Meeting of States Parties), bit.ly/2MBTReportingGuide2015.

[80] UNGA, Report of the Secretary-General, “Status of the human rights treaty body system,” A/71/118, 18 July 2016, para. 35.

[81] Participation in service and program implementation was reported in at least the following 25 States Parties: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, BiH, Burundi, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, DRC, Croatia, El Salvador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Iraq, Jordan, Mozambique, Peru, Senegal, Serbia, South Sudan, Sudan, Thailand, Uganda, and Yemen.

[82] Maputo Action Plan Action #17.

[83] Of the 31 States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty, all except Somalia and Sudan are also States Parties to CEDAW.

[84] The Committee of CEDAW General Recommendation 30 on women in conflict prevention, conflict, and post-conflict situations, and General Recommendation 27 on older women and protection of their human rights are also particularly applicable.

[85] As well as Mine Ban Treaty states not party Lao PDR and Vietnam. Email from Calza Bini Arianna, GMAP, 12 October 2016.

[86] These fact sheets can be accessed at the Monitor, “Victim Assistance Resources,” the-monitor.org/en-gb/our-research/victim-assistance.aspx.

[87] See, Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, “Victim assistance and CRPD Article 11: Situations of risk and humanitarian emergencies,” 25 June 2015, staging.monitor.lastexitlondon.com/media/2034853/MonitorBriefingPaper_VAandArticle11_25June2015.pdf.

[88] Afghanistan, BiH, Burundi, Chad, DRC, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau, Iraq, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Uganda, Yemen, and Zimbabwe.

[89] World Health Organization and World Bank, World report on disability, Geneva, 2011, p. 37, www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/en.

[90] “Charter on Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Action,” humanitariandisabilitycharter.org.