Landmine Monitor 2018

Victim Assistance

Introduction

The 1997 Mine Ban Treaty was the first disarmament convention committing States Parties to provide assistance to the victims of a specific weapon. The components of victim assistance include, but are not restricted to: data collection and needs assessment with referral to emergency and continuing medical care; physical rehabilitation, including prosthetics and other assistive devices; psychological support; social and economic inclusion; and relevant laws and public policies.

The definition of “landmine victim” was agreed by States Parties in the Final Report of the First Review Conference(paragraph 64) formally adopted at the Nairobi Summit in 2004 as based on the then generally accepted understanding as“those who either individually or collectively have suffered physical or psychological injury, economic loss or substantial impairment of their fundamental rights through acts or omissions related to mine utilization.” Landmine victim, according to this widely accepted understanding of the term, includes survivors,[1] as well as affected families and communities.[2]

In the penultimate year for the Mine Ban Treaty’s Maputo Action Plan 2014–2019, this chapter principally takes stock of changes, progress, and challenges to the provision of assistance in States Parties with significant numbers of survivors and needs. It draws from reporting on the activities and challenges of hundreds of relevant programs implemented through government agencies, international and national organizations and NGOs, survivors networks and similar community-based organizations, as well as other service providers.

In most States Parties some efforts to improve the quality and quantity of health and physical rehabilitation programs for survivors were undertaken. However, after a trend of large reductions in services available in recent years due to decreases in resources, in 2017–2018 many countries saw near-stagnation in the remaining core assistance services for mine/explosive remnants of war (ERW) victims. Services remained largely centralized, preventing many mine/ERW survivors who live in remote and rural areas from accessing those services. The needs remain great, including in the newest States Parties, Palestine and Sri Lanka.

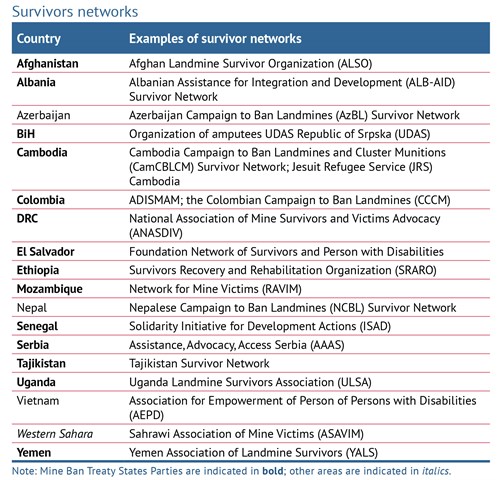

Many existing coordination mechanisms had some survivor participation, but States Parties were yet to fulfill their commitments to building the capacity of survivors through their representative organizations. Most survivor networks struggled to provide essential local support not available through larger NGOs or existing state services.

The Monitor website includes comprehensive country profiles detailing the human impact of mines, cluster munitions, and other ERW and examining progress in victim assistance in some 70 countries, including both States Parties and states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty and the Convention on Cluster Munitions.[3] A collection of thematic overviews, briefing papers, factsheets, and infographics related to victim assistance produced since 1999 is available through the Victim Assistance Resources portal on the Monitor website.[4]

Victim Assistance Under the Maputo Action Plan

At the Mine Ban Treaty Third Review Conference held in Maputo in 2014, States Parties formally declared that they remain very much aware of their “enduring obligations to mine victims.”[6] The actions of the Maputo Action Plan adopted at that conference can be summarized as follows:

- Assess the needs; evaluate the availability and gaps in services; and make referrals to existing services.

- Ensure the inclusion as well as the full and active participation of mine victims and their representative organizations in all matters that affect them; enhance their capacity.

- Increase the availability of and accessibility to services, opportunities, and social protection measures; strengthen local capacities and enhance coordination.

- Address needs and guarantee rights in an age- and gender-sensitive manner.

- Develop time-bound and measurable objectives and communicate progress annually.

- Enhance plans, policies, and legal frameworks.

- Report on measurable improvements in advance of the next review conference.

States Parties commit to addressing victim assistance objectives “with the same precision and intensity as for other aims of the Convention.”[7] The plan also affirms the need for States Parties to continue carrying out the actions of the previous Cartagena Action Plan in order to make assistance available, affordable, accessible, and sustainable.[8]

Assessing the needs

States Parties commit to assess the needs of mine victims. This commitment includes assessing the availability and gaps in services and support, and existing or new requirements activities needed to meet the needs of mine victims in the frameworks of disability, health, education, employment, development, and poverty reduction. They should also use this assessment activity as an opportunity to refer mine victims to existing services.[9]

In most States Parties no structured national needs assessments surveys were conducted in 2017 or into 2018. However, Mine Action Centers and service providers often collected information on mine victims in an ongoing manner in conjunction with other victim assistance and program activities.

Disability survey, including through national census questions, was discussed in many national victim assistance contexts. The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) (Article 31) calls on States Parties to collect information, including statistical and research data, and to disaggregate this information to identify barriers faced by persons with disabilities in exercising their rights. A common theme linking CRPD obligations and victim assistance data collections was the potential use of the Washington Group disability measurement tools.[10] These are believed to be able to improve disability statistics and monitor the 2030 Agenda against indicators.[11]

Plans and policies

At the national level and within the community of the Mine Ban Treaty, the Maputo Action Plan calls for activities addressing the specific needs of victims, while incorporating relevant actions into the appropriate sectors including disability, health, social welfare, education, employment, development, and poverty reduction.[12]

States Parties committed to have time-bound and measurable objectives to implement national policies and plans that will tangibly contribute to the main goals of victim assistance.[13] In 2017–2018, 13of the 33 States Parties with victims and needs had victim assistance plans or relevant disability plans in place.[14]

Sudan adopted a victim assistance plan in 2017 through an approval process that started in 2016. Through 2017 in Colombia, some 19 municipalities had adopted area official plans for assistance for mine/ERW victims, and 20 municipalities had mapped out specific referral “pathways,” guiding survivors to their rights, services, and benefits available. This almost already reached the planned target for 2014–2018 of 22 municipal pathways for assistance. In 2018, Albania was in the process of national plan review. In BiH, the Victim Assistance Sub-Strategy 2009–2019 of the Mine Action Strategy remains in place, but a mid-way review was not yet adopted. Iraq continued to report that it developed annual victim assistance planning. Guinea-Bissau had reported on objectives of a victim assistance strategy in 2013, but the objectives, including establishing a new victim assistance coordination mechanism, were not reported against.

In 2018, victim assistance dialogues focused on the development of tangible strategic planning were held in Iraq and Uganda, in September and October respectively, hosted by national authorities with Implementation Support Unit (ISU) support and European Union (EU) funding.[15]

Coordination

In 2017, 21 of the 33 States Parties had active victim assistance coordination mechanisms linked with disability coordination mechanisms that considered the issues relating to the needs of mine/ERW survivors.[16]

A coordination mechanism for victim assistance in BiH received an official mandate in 2018 for the first time, after having restarted informal coordination in 2017 after a long pause.

Chad renewed victim assistance coordination in 2017.

Inclusion and active participation of mine victims

In the Maputo Action Plan, each State Party has committed to do its “utmost to enhance the capacity and ensure the inclusion and full and active participation of mine victims. and their representative organisations in all matters that affect them.”[17] In 2017, survivors and their representative organizations, including survivor networks and disabled persons’ organizations (DPOs), participated in coordination activities in at least 18 of the 21 States Parties with active mechanisms.[18] However, states almost never report how survivor input is considered or acted upon. Survivors’ representative organizations and other service providers reported in some states that the contributions of survivors were not seriously taken into account.

Action plan commitments also include capacity-building, but as is the case with full and active participation, state initiatives for capacity-building for participation of mine victims were also almost never reported. One exception was the Quality of Life survey in Cambodia. Also, the need for improved education for survivor representation in Uganda was recognized.

In addition to examining the 33 States Parties, the Monitor identified many states and areas with mine victims where survivors networks reported developments in 2017 and into 2018. Unfortunately, in most countries, survivor networks struggled to maintain their operations with decreasing resources available. Networks in States Parties Croatia, Mozambique, and Somalia were largely unable to implement essential activities in much of 2017 and 2018. Activities of the national survivors’ network in Afghanistan were primarily advocacy and awareness-raising. Many others managed to maintain essential linkages at the community level and provide support, advice, and referrals as possible.

Availability of and Accessibility to Services

States Parties committed to “increase availability of and accessibility to appropriate comprehensive rehabilitation services, economic inclusion opportunities and social protection measures…including expanding quality services in rural and remote areas and paying particular attention to vulnerable groups.”[19] The following changes, progress, and challenges were reported for 2017 in the 33 States Parties with significant numbers of survivors and needs.

Medical care and physical rehabilitation, including prosthetics

Medical care services for mine/ERW survivors were strengthened in some countries in the Sub-Saharan Africa region, including in Ethiopia and Senegal. In many countries, however, survivors continued to have to travel long distances in order to access services. In Chad,health services in mine-contaminated areas were limited, with few qualified personnel. In Guinea-Bissau, large parts of the population do not have access to healthcare. In Mozambique, survivors reported a general lack of medication, especially anti-retroviral medications for persons living with HIV/AIDS. In Uganda, there were regular shortages of medicines during gaps in the scope of budget allocations and quality healthcare remained unaffordable and inaccessible to many survivors.

In Iraq and Yemen, increased training and resources were provided in response to the greater demand for services caused by conflict. In Iraq, healthcare services for persons with disabilities decreased over time. However, international organizations and NGOs provided specific interventions, including for surgical care to the war-injured persons of Mosul. In Yemen, there was no specific mechanism in place for managing the responses to new mine/ERW survivors. Only 50% of health facilities remained functional, while the half that remained faced severe shortages in medicines, equipment, and staff. The influx of Syrian refugees into Jordan put a strain on available public health services and resources.

In Afghanistan, the health sector was not reaching as many people as needed and the quality of the services provided by the governmental hospitals dropped.

In Croatia, improved emergency response time also benefited mine/ERW survivors. Medical staff and trauma doctors from hospitals located in mine/ERW-contaminated areas in Tajikistan received training on managing weapon wounds.

The World Health Organization (WHO) released recommendations on health-related rehabilitation linked to the Sustainable Development Goals in 2017. In January 2018, the WHO held a general consultation outlining its activities for the next three years. This includes integrating rehabilitation into universal health coverage (UHC) budgeting and planning, developing a package of priority rehabilitation interventions, and establishing tools and resources to strengthen the health workforce for rehabilitation.

Measures taken to increase availability of physical rehabilitation services were reported in several Sub-Saharan States Parties, including Burundi, Chad, Eritrea, Somalia, and Sudan. However, shortages of raw materials and financial resources were an obstacle to the development of the physical rehabilitation sector in most countries, even those where improvements were noted, including Angola, Somalia, and Zimbabwe. In the DRC, the decrease in available resources in recent years significantly impacts the capacities of NGOs to operate. An international NGO started a new physical rehabilitation pilot project in 2017 in the DRC. In Senegal, due to deteriorating equipment and a constant shortage of raw materials, the physical rehabilitation center in the mine-affected region did not deliver any new prosthetic devices in 2017. Access to rehabilitation for survivors from Senegal was available through an agreement with a center in Guinea-Bissau.

In Afghanistan, four new physical rehabilitation centers were established during the Maputo Action Plan period, however several more such centers were still needed. In Cambodia, some progress was reported in creating consistent reporting systems for the rehabilitation sector and the planning for handover of centers to government funding and management.

In Colombia, there was a significant increase in geographical coverage of rehabilitation due to the signing of agreements between the government and a non-state armed group that allowed access to areas that were previously labeled difficult access “red zones.” However, overall physical rehabilitation remained largely centralized in large cities. Survivors in rural areas faced challenges to access rehabilitation services due to transport and food costs. For the first time, a regional forum was held with representatives of rehabilitation centers from Ecuador, El Salvador, and Nicaragua. In Nicaragua, a central body for physical rehabilitation actors was under development. In El Salvador, planning for the construction of a new satellite prosthetics unit began.

In Albania, raw materials and components for the repair and production of prostheses were secured for the rehabilitation center in the area where most survivors live. In BiH and Serbia, while provision of orthopedic devices is mandated by law, access was sometimes impeded by excessive procedural demands. Staff from municipal centers for physical rehabilitation in BiH were introduced to the method of integrating peer support during the rehabilitation of mine survivors.

In Algeria, mine/ERW survivors and other persons with disabilities continued to have access to most prosthetic and assistive devices free-of-charge. In Iraq, a 30% decrease in the number of assistive devices between 2014 and 2017 was an indicator of the ongoing necessity to enhance support to existing rehabilitation services for survivors. A much-needed new rehabilitation center was launched in Mosul in 2018. In Palestine, the only prosthetic center in Gaza faced significant strain on its limited resources while addressing an increase in patients with amputations among protesters who had been shot in the legs. In Yemen, increased support to the physical rehabilitation centers sector was reported in response to the needs caused by ongoing conflict, but availability of assistance overall remained far from adequate for meeting those needs.

Economic inclusion, education, psychosocial support

Projects to encourage the economic inclusion of survivors were severely lacking in Angola, the DRC, Ethiopia, Senegal, Somalia, South Sudan, and Uganda. Some economic-inclusion programs were reported in Burundi, Chad, Guinea-Bissau, Ethiopia, Senegal, South Sudan, and Sudan.

In Albania, some vocational training was reported. However, the number of available economic-inclusion activities and beneficiaries has declined. A two-year socio-economic inclusion project for mine/ERW survivors in BiH was underway. In Croatia, regulations on the employment of persons with disabilities and professional rehabilitation needed to be amended to be aligned with existing legislation. Also in Croatia, a new center for professional rehabilitation was established.

In Iraq, DPOs reported that the number of persons with disabilities who received state-run vocational training seemed insignificant to the size of the population of persons with disabilities. Economic-inclusion activities were nearly nonexistent in Yemen, where livelihood activities by the survivors’ network stopped due to lack of funding.

Psychosocial services were deployed to four regions that had previously not been reached in Eritrea. Psychological support services in a mine/ERW victim assistance context were extremely limited, or near to non-existent, in Angola, the DRC, Mozambique, Senegal, Somalia, South Sudan, Uganda, and Zimbabwe. In South Sudan, where public mental health services are virtually non-existent,some 40% of the population show psychological effects of trauma from conflict and violence. South Sudan has one of the highest rates of suicides, and suicide rates in the refugee camps have spiked, while the lives of survivors and other persons with disabilities is increasingly precarious.[20] Ethiopia launched safety net programs intended to benefit persons with disabilities, including landmine survivors.

Afghanistan and Cambodiarequired planning and structures to make available psychosocial support.

Psychological support was among the most serious needs of survivors inAlbania, but no recent progress was reported. The provision of continuing psychosocial support remained weak in Croatia throughout 2017, despite there being 21 psychosocial centers.

The availability of psychological support and follow-up trauma care in Iraq, including for internally displaced persons, remained inadequate to meet needs. At least two new projects providing ongoing psychosocial support were reported in 2018. InYemen,international NGOs continued to provide some mental health and psychosocial support activities to the war-wounded and their families. However, the national survivors’ network was only able to provide psychological support to a very small number of survivors.

Since 2010, the WHO community-based rehabilitation (CBR) guidelines, and how they can be used to start or strengthen CBR programs for victims of landmines, have been promoted among victim assistance actors in States Parties.[21] Monitor reporting includes many examples of CBR programs that contribute to victim assistance implementation, including the following:

In Peru, a regional-targeted program continued to improve the quality of life of persons with disabilities and their families in the mine-affected Tumbes region in 2017.

In Angola, an NGO-run CBR program expanded to seven new provinces.In Ethiopia, an NGO provides CBR in three regional states.In Eritrea, the CBR program is the main provider of physical therapy and psychosocial support to landmine and ERW survivors and persons with disabilities. In Senegal, a national CBR program was on the verge of being approved.

In Afghanistan, NGO-led CBR activities are implemented in 12 of 34 provinces. In Cambodia, CBR services are available in 25 provinces.

Guaranteeing rights in an age- and gender-sensitive manner

The Maputo Action Plan speaks of “the imperative to address the needs and guarantee the rights of mine victims, in an age- and gender-sensitive manner.”[22]

Gender considerations

While men and boys are the majority of reported casualties, women and girls may be disproportionally disadvantaged as a result of mine/ERW incidents and suffer multiple forms of discrimination as survivors. To guide a rights-based approach to victim assistance for women and girls, States Parties can apply the principles of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW).[23] Implementation of CEDAWby States Parties to that convention should ensure the rights of women and girls and protect them from discrimination and exploitation.[24]

Gender was a key consideration in victim assistance programming, but reporting was often limited to statistical disaggregation of casualties and service beneficiaries. Some other details, however, were available. In Somalia women with disabilities continue to be vulnerable to sexual violence and forced marriage. The government of Somalia proposed to focus on women and girls in their efforts to support persons with disabilities to address the double stigma of gender and disability. In Iraq, gender sensitive services are provided to most females through the provision of specialized female staff in rehabilitation and medical centers. The same applies to males.In Yemen, women faced additional challenges accessing medical care due to the lack of gender-sensitive services, including a lack of female rehabilitation professionals.

Age considerations

Child survivors have specific and additional needs in all aspects of assistance. In 2017 and 2018, inclusive education and age-sensitive assistance were far from adequate in most countries. In this regard, the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) is particularly relevant to the implementation of victim assistance with a rights-based approach.[25]

The annually updated Monitorfactsheet on the Impact of Mines/ERW on Children contains more details on issues pertaining to children, youth, and adolescents.[26]

National legal frameworks

According to the Maputo Action Plan, States Parties collectively agree that victim assistance should be integrated into broader national policies, plans, and legal frameworks and that they will make “enhancements” to the legal frameworks in effect as a means of operationalizing the integration. Some new plans and policies were adopted in the reporting period, and several more had been drafted and were pending endorsement.

Ethiopia National Disability adopted the Mainstreaming Guideline with specific guidance for the health sector and vocational training providers. Mozambique is in the process of drafting a national law for the protection and promotion of the rights of persons with disabilities. In Somalia, a bill to establish a National Agency for Persons with Disabilities was approved in 2018. South Sudan has developed a National Disability and Inclusion Policy.

Jordan adopted a new comprehensive law on the rights of persons with disabilities.

The process of amending discriminatory national disability legislation in Afghanistan was completed.

Tajikistan, not party to the CRPD, introduced a National Program on Rehabilitation of Persons with Disabilities, covering physical rehabilitation services and social inclusion.

Broader Frameworks for Assistance

The Maputo Action Plan calls for activities addressing the specific needs of victims and also emphasizes the need to simultaneously integrate victim assistance into other frameworks, including disability, health, social welfare, education, employment, development, and poverty reduction.[27] It also recognizes that in addition to integrating victim assistance, States Parties need to, in actual fact, “ensure that broader frameworks are reaching mine victims.”

Many of these frameworks have their own representative international administrations, guidance documents, plans, and objectives that may also be reflected in national-level activities that can reach survivors, families, and communities.

Since the emergence of victim assistance through the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty, other weapons-related conventions have adopted this rapidly emerging norm. The 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions codified the expanded principles and commitments of victim assistance into binding international law; these were introduced into the planning of the Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW) Protocol V on ERW in 2008, and most recently included in the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of NuclearWeapons.

The CRPD is the international human rights legal instrument that has been most discussed in relation to the implementation of victim assistance. The linkages between rights-based victim assistance and the CRPD are particularly useful for implementation through integration and synergy. Only five States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty with significant numbers of survivors are not party to the CRPD. Three of those are signatories to the CRPD: Chad, Somalia, and Tajikistan. Tajikistan signed in March 2018 and Somalia in October 2018. Eritrea and South Sudan have not yet signed or acceded to the CRPD. Victim assistance is very often linked with, or included in, the national CRPD coordination mechanisms of countries that are party to both the Mine Ban Treaty and the CRPD. Furthermore, some states initial reports submitted under Article 35 of the CRPD have referred to victim assistance and landmine survivors. Although the CRPD does not establish new human rights, it does provide much greater clarity to the obligations of states to promote, protect, and ensure the rights of persons with disabilities and presents the concepts for those rights to become reality through implementation of the convention.

Adopted 70 years ago this year, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) established for the first time the fundamental human rights to be universally protected. The basis of many elements of the CRPD that inform understandings of the components, or pillars, of victim assistance are found in the UDHR, including healthcare (and rehabilitation), employment, education, and participation.[28]

The rights of peasants and other people working in rural areas

In September 2018, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas was adopted by the Human Rights Council. It includes several aspects relevant to survivors and indirect victims of mines.[29]

The declaration is compatible with the implementation of Maputo Action Plan Article 15, which “entails removing physical, social, cultural, economic, political and other barriers, including expanding quality services in rural and remote areas and paying particular attention to vulnerable groups.” State delegations that endorsed the declaration on the Rights of Peasants included Mine Ban Treaty States Parties with recorded mines/ERW victims: Algeria, Ecuador, El Salvador, Kenya, Nicaragua, Palestine, and the Philippines.

Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are highly complementary to the rights-based aims of victim assistance under the Mine Ban Treaty. They also offer opportunities for bridging between relevant frameworks. The SDGs, a set of 17 aspirational goals with corresponding targets and indicators that all UN member states are expected to use to frame policies and stimulate actionfor positive change in 2015–2030, are designed to address the economic, social, and environmental dimensions of sustainable development. Their emphasis is on reaching the most marginalized persons, commonly phrased as “leaving no-one behind.”[30]

Conflict and humanitarian emergencies

An Inter-Agency Standing Committee(IASC) Task Team on Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Action established in 2016 continued to develop and refine implementation guidelines related to the charter on the Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities into Humanitarian Action in 2018.[31]

Two States Parties with significant numbers of survivors and ongoing conflict, the DRC and Yemen, had a Level-3 IASC system-wide response activated in 2017–2018.[32] Syria, a state not party to the Mine Ban Treaty, was the only other country to have a Level-3 response active in the period.

In Yemen, the ongoing conflict dramatically increased demand for emergency and ongoing medical care beyond the capacity of the medical system. Additionally, the mine action center had to suspend victim assistance activities in 2018.

A UN strategic review for 2018 reclassified Afghanistan from a post-conflict country to one in active conflict.[33] Movement restrictions due to conflict in Afghanistan were among the persistent obstacles to victim assistance in some parts of the country. Conflict continued to cause damage and disruption to social healthcare services, while trauma, physical injuries, and mass displacement increased the need for those services.Security constraints prevented some rehabilitation outreach services from operating. Other States Parties where conflict and unstable security situations similarly impacted implementation of victim assistance included Iraq, Palestine, Somalia, and South Sudan. In Somalia, insecurity was widespread and the indistinct nature of conflict front lines hindered delivery of assistance by many international humanitarian agencies, particularly to areas under the control of non-state armed groups.

[1] A “survivor” is a person who was injured by mines/explosive remnants of war (ERW) and lived.

[2] See, “Final Report of the First Review Conference,” APLC/CONF/2004/5, 9 February 2005; and “Nairobi Action Plan 2005–2009,” www.icbl.org/media/933290/Nairobi-Action-Plan-2005.pdf.

[3] Country profiles are available on the Monitor website, www.the-monitor.org/cp. Findings specific to victim assistance in states and other areas with victims of cluster munitions are available through Landmine Monitor 2018’s companion publication, Cluster Munition Monitor 2018, www.the-monitor.org/CMM18

[4] See, the Monitor, “Victim Assistance Resources,” undated, www.the-monitor.org/en-gb/our-research/victim-assistance.aspx.

[5] In addition, States Parties Mali and Ukraine, both of which have had hundreds of mine/ERW casualties in the past two years, may be considered to have significant numbers of survivors with great needs for assistance that remain unreported.

[6] “MAPUTO +15: Declaration of the States Parties to the Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on Their Destruction,” adopted 27 June 2014, www.apminebanconvention.org/eu-council-decision/maputo-15.

[7] “Maputo Action Plan,” Maputo, 27 June 2014, p. 3, bit.ly/MaputoActionPlan.

[8] “Cartagena Action Plan 2010–2014: Ending the Suffering Caused by Anti-Personnel Mines,” Cartagena, 11 December 2009, bit.ly/MBTCartagenaPlan.

[9] Maputo Action Plan Action #12.

[10] The Washington Group on Disability Statistics was established under the United Nations Statistical Commission to develop internationally comparable population-based measures of disability. Washington Group on Disability Statistics, www.washingtongroup-disability.com.

[11] UN, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Demographic and Social Statistics, Statistics Division, United Nations Disability Statistics Programme, https://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic-social/sconcerns/disability/.

[12] Maputo Action Plan Actions #12 to #18.

[13] Maputo Action Plan Action #13.

[14] Albania, Angola, BiH, Cambodia, Colombia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Jordan, Mozambique, Peru, Sudan, Tajikistan, and Thailand. Algeria, Chad, Senegal, and Sri Lanka had plans pending approval or formal adoption.

[15] In August 2017, the Council of the EU adopted Decision (CFSP) 2017/1428 in support of the implementation of the Mine Ban Treaty through the treaty’s ISU as the technical implementer to support efforts on the part of States Parties, including towards the implementation of victim assistance.

[16] The states with coordination mechanisms in 2017–2018 were: Afghanistan, Albania, Angola, BiH, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, Croatia, DRC, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Iraq, Jordan, Mozambique, Peru, Serbia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, and Turkey. Angola had intermittent and infrequent coordination meetings that lacked disability sector integration, which is a key sustainability issue.

[17] Maputo Action Plan Action #16.

[18] Afghanistan, Albania, Angola, BiH, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, Croatia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Iraq, Jordan, Mozambique, Peru, South Sudan, Sudan, Tajikistan, and Thailand.

[19] Maputo Action Plan Action #15.

[20] South Sudan reported that landmine survivors and other persons with disabilities “now experience death as a result of poverty.” Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2017), p. 13.

[21] The WHO CBR Guidelines were the subject of focused training for government victim assistance focal points at the Mine Ban Treaty Tenth Meeting of States Parties in 2010; a victim assistance experts’ program was dedicated to their Geneva launch and training on their practical application, bit.ly/MBT10MSPVA.

[22] Maputo Action Plan Action #17.

[23] Of the 33 States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty, all except Somalia and Sudan are also States Parties to CEDAW.

[24] The Committee of CEDAW General Recommendation 30 on women in conflict prevention, conflict, and post-conflict situationsand General Recommendation 27 on older women and protection of their human rights are also particularly applicable.

[25] Some of the resources on children and victim assistance include:Sebastian Kasack, Assistance to Victims of Landmines and Explosive Remnants of War: Guidance on Child-focused Victim Assistance (UNICEF, November 2014); Austria and Colombia, “Strengthening the Assistance to Child Victims,” Maputo Review Conference Documents, June 2014, www.maputoreviewconference.org/fileadmin/APMBC-RC3/3RC-Austria-Colombia-Paper.pdf; and Colombia, “Guide for Comprehensive assistance to boys, girls and adolescent landmine victims – Guidelines for the constructions of plans, programmes, projects and protocols,” Bogota, 2014, bit.ly/ColombiaLandmineVA2014.

[26] These factsheets, produced since 2009, can be accessed at the Monitor, “Victim Assistance Resources,” www.the-monitor.org/en-gb/our-research/victim-assistance.aspx.

[27] Maputo Action Plan Actions #12 to #18.

[28] Drawn from Marianne Schulze, “Understanding the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities,” Handicap International, September 2009.

[29] United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas, Human Rights Council 39thSession, A/HRC/39/L.16, 26 September 2018.

[30] Persons with disabilities are referred to directly in the SDGs: education (Goal 4), employment (Goal 8), reducing inequality (Goal 10), and accessibility of human settlements (Goal 11), in addition to including persons with disabilities in data collection and monitoring (Goal 17). With an emphasis on poverty reduction, equality, and inclusion, the SDGs also recognize the need for the “achievement of durable peace and sustainable development in countries in conflict and post-conflict situations.”

[31] “Charter on Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Action,” undated but 2016, http://humanitariandisabilitycharter.org/.

[32] Such an activation occurs when a humanitarian situation suddenly and significantly changes, and it is clear that the existing capacity to coordinate and deliver humanitarian assistance and protection does not match the scale, complexity, and urgency of the crisis. Based on an analysis of five criteria: scale, complexity, urgency, capacity, and reputational risk. IASC, “L3 IASC System-wide response activations and deactivations,” 4 April, 2017, bit.ly/IASCL3.

[33] UNOCHA, “2018 Afghanistan Humanitarian Needs Overview,” 1 December 2017,bit.ly/2018AgfHumNeedsOCHA.