Landmine Monitor 2021

The Impact

Jump to a specific section of the chapter:

Assessing the Impact: Contamination | Casualties

Coordination: Clearance | Risk Education | Victim Assistance

Addressing the Impact: Clearance | Risk Education | Victim Assistance

This chapter highlights developments and challenges in assessing and addressing the impact of antipersonnel mines. The first part of this overview covers contamination and casualties, while the second part focuses on addressing the impact through clearance, risk education, and victim assistance. These make up three of the five core components or “pillars” of mine action.

This overview documents progress under the Oslo Action Plan—the five-year action plan of the Mine Ban Treaty, adopted in November 2019. The plan is consistent with the fulfillment of the objectives of the treaty, whereby States Parties declare that they are:

“Determined to put an end to the suffering and casualties caused by anti-personnel mines, that kill or maim hundreds of people every week, mostly innocent and defenseless civilians and especially children, obstruct economic development and reconstruction, inhibit the repatriation of refugees and internally displaced persons, and have other severe consequences for years after emplacement.”

As of October 2021, there were 33 States Parties that had declared obligations under Article 5 of the Mine Ban Treaty to clear contaminated land. In 2020, despite the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, most States Parties reported undertaking clearance in areas under their jurisdiction and control. A total of 146km² of contaminated land was cleared, while approximately 135,583 antipersonnel mines were cleared and destroyed. In 2020, Chile and the United Kingdom (UK) both declared completion of their Article 5 clearance obligations.

However, States Parties Guinea-Bissau, Mauritania, and Nigeria were added back on to the list of States Parties with clearance obligations due to having either newly discovered or, in the case of Nigeria, new mine contamination. Progress towards the aspirational goal “to clear all mined areas as soon as possible, to the fullest extent by 2025,” as agreed by States Parties at the Third Review Conference of the Mine Ban Treaty in Maputo in June 2014 and reaffirmed at the Fourth Review Conference in Oslo in 2019, has stalled, with few States Parties on target to meet their deadlines.

Exceptionally high numbers of casualties resulting from landmines and explosive remnants of war (ERW) continued to be recorded during 2020, following a sharp rise in casualties caused by increased conflict and contamination since 2015. The total of 7,073 mine/ERW casualties in 2020 represents more than double the number of casualties in 2013, which saw the fewest annual casualties on record. Casualties were recorded in 51 countries and three other areas in 2020. For the first time, Syria recorded the highest number of annual causalities, followed by Afghanistan. The majority of casualties in 2020 were reported in countries experiencing armed conflict and which suffered contamination with mines of an improvised nature.

Mine/ERW risk education was conducted in at least 26 States Parties during 2020, albeit under unprecedented and challenging conditions. Delivery was adversely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic as physical distancing, movement restrictions, and school closures prevented many of the usual risk education activities from being conducted. However, in line with Action #31 of the Oslo Action Plan, States Parties and operators responded and adapted to these changing circumstances by devising new ways to deliver the life-saving messages through mass media, mobile phone apps, social media platforms, and local networks of community volunteers.

At least 34 States Parties have responsibility for significant numbers of mine victims—these states have “the greatest responsibility to act, but also the greatest needs and expectations for assistance.”[1] The Oslo Action Plan includes commitments to enhance the core victim assistance components of emergency medical response, ongoing healthcare, rehabilitation, psychosocial support, and socio-economic inclusion. It also includes a commitment on protection of victims in situations of risk, including armed conflict, humanitarian emergencies, and natural disasters. This action has become particularly important in the context of states meeting victim assistance objectives during the COVID-19 pandemic, while at the same time addressing the changes and challenges brought about by pandemic-related restrictions.

Antipersonnel mine contamination

Antipersonnel mine contamination in States Parties

States Parties with Article 5 obligations

As of October 2021, a total of 33 States Parties had declared an identified threat of antipersonnel mine contamination on territory under their jurisdiction or control, and therefore have obligations under Article 5 of the Mine Ban Treaty.

States Parties that have declared Article 5 obligations as of October 2021

|

Afghanistan |

Eritrea |

Serbia |

|

Angola |

Ethiopia |

Somalia |

|

Argentina* |

Guinea-Bissau |

South Sudan |

|

BiH |

Iraq |

Sri Lanka |

|

Cambodia |

Mauritania |

Sudan |

|

Chad |

Niger |

Tajikistan |

|

Colombia |

Nigeria |

Thailand |

|

Croatia |

Oman |

Turkey |

|

Cyprus** |

Palestine |

Ukraine |

|

Dem. Rep. Congo |

Peru |

Yemen |

|

Ecuador |

Senegal |

Zimbabwe |

*Argentina was mine-affected by virtue of its assertion of sovereignty over the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas. The United Kingdom (UK) also claims sovereignty and exercises control over the territory, and completed mine clearance of the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas in 2020. Argentina has not yet acknowledged completion.

**Cyprus states that no areas contaminated by antipersonnel mines remain under Cypriot control.

States Parties that have completed clearance

Under Article 5 of the Mine Ban Treaty, States Parties are required to clear all antipersonnel mines as soon as possible, but not later than 10 years after becoming party to the treaty.

At the Eighteenth Meeting of States Parties in November 2020, Chile formally announced having completed clearance of all known mined areas within its territory on 27 February 2020.[2] The United Kingdom (UK) also announced completion of its Article 5 obligations in November 2020, following the clearance of the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas ahead of its deadline of 1 March 2024.[3]

Since the Mine Ban Treaty came into force in 1999, 33 States Parties have reported clearance of all antipersonnel mines from their territory. State Party El Salvador completed clearance in 1994, before the treaty came into force.

States Parties that have declared fulfilment of clearance obligations since 1999

|

1999 |

Bulgaria |

2010 |

Nicaragua* |

|

2003 |

Costa Rica |

2011 |

Nigeria** |

|

2004 |

Djibouti, Honduras, Suriname |

2012 |

Republic of the Congo, Denmark, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau,* Uganda |

|

2005 |

Guatemala |

2013 |

Bhutan, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Venezuela*** |

|

2006 |

North Macedonia |

2014 |

Burundi |

|

2007 |

Eswatini (formerly Swaziland) |

2017 |

Algeria,* Mozambique* |

|

2008 |

France, Malawi |

2018 |

Jordan, Mauritania** |

|

2009 |

Albania, Rwanda, Tunisia,*** Zambia |

2020 |

Chile, UK |

*Algeria, Nicaragua, and Mozambique have reported, or are suspected to have, residual contamination.

**Guinea-Bissau, Mauritania, and Nigeria have reported finding new contamination.

***Tunisia and Venezuela are suspected to have improvised mine contamination.

Several States Parties to have declared themselves free of antipersonnel mines later discovered previously unknown mine contamination, or were required to verify that areas had been cleared to humanitarian standards.[4] Burundi, Germany, Greece, Hungary, and Jordan each declared the fulfilment of their Article 5 obligations several years after their initial declarations.

States Parties that have reported new contamination

If a State Party discovers a mined area under its jurisdiction or control after its original or extended Article 5 deadline has expired, it has an obligation to inform all States Parties of the discovery and to undertake to clear and destroy all antipersonnel mines in the area as soon as possible, and before the next Meeting of States Parties or Review Conference.[5]

Three States Parties that previously declared themselves free of antipersonnel mines have since reported further contamination, and submitted extension requests in 2020 and 2021.

Guinea-Bissau declared fulfilment of its clearance obligations under Article 5 of the Mine Ban Treaty on 5 December 2012. Yet in June 2021, Guinea-Bissau reported residual contamination from mines/ERW and submitted an extension request until 31 December 2022.[6]

Mauritania, which declared itself free of mines in 2018, reported finding new contamination in 2019 and was granted a one-year extension in 2020 to conduct survey to gain a more accurate estimate of contamination.[7] Following this initial one-year extension, Mauritania submitted a fourth request to extend its clearance deadline in June 2021.[8]

Nigeria announced that it had fulfilled its Article 5 obligations in 2011, but indicated newly-mined areas in 2019.[9] Nigeria submitted an extension request in November 2020, and received an interim extension until 31 December 2021 “to present [a] detailed report on contamination, progress made and work plan for implementation.”[10] Nigeria submitted a second request in May 2021, to be considered at the Nineteenth Meeting of States Parties in November 2021.[11]

States Parties with residual contamination

Four States Parties were known or suspected to have residual contamination in 2020.

Algeria declared fulfilment of its Article 5 obligations in 2017, but continues to find and destroy antipersonnel mines on its southwestern borders. In 2020, Algeria reported that 8,813 antipersonnel mines were found and destroyed, an increase from the 4,499 found in 2019.[12] Algeria reported that the mined areas are under its jurisdiction and control, and that the mines are immediately reported and destroyed, in accordance with the treaty.[13]

There have been several mine/ERW casualties reported in Kuwait since 1990. In 2018, there were reports of torrential rain having unearthed landmines, presumed to be remnants of the 1991 Gulf War.[14] The mines are believed to be present mainly on its borders with Iraq and Saudi Arabia; in areas used by shepherds for grazing animals. Kuwait has not made a formal declaration of contamination in line with its Article 5 obligations.

In Mozambique, four small suspected mined areas totaling 1,881m² were reported to be submerged underwater in Inhambane province.[15] At the Mine Ban Treaty intersessional meetings in June 2018, Mozambique reiterated its commitment to address these areas once the water level had receded and access could be gained, and said the National Demining Institute conducted regular monitoring. Mozambique noted that it believed there was little probability that mines would be detected in the submerged areas.[16] Mozambique has provided no further updates since 2018 on the status of these mined areas.

Nicaragua declared completion of clearance under Article 5 in April 2010, but has since found residual mine/ERW contamination. In 2018, Nicaragua reported that its contingency operations answered 13 reports made by the public, resulting in the clearance of 2,849m² and removal and destruction of 29 items of ERW. Nicaragua confirmed these operations would continue through 2019.[17] In May 2020, two mines exploded in El Bayuncun, San Fernando, near the border with Honduras. The first mine injured one person and the second injured four people from a rescue party.[18]

Extent of contamination in States Parties

States Parties Afghanistan, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Cambodia, Croatia, Ethiopia, Iraq, Turkey, Ukraine, and Yemen have all reported massive antipersonnel landmine contamination (more than 100km²). However, the extent of contamination in at least two of these countries— Ethiopia and Ukraine—is likely to be considerably less once survey is conducted.

Large contamination by antipersonnel landmines (20–99km²) is reported in five States Parties: Angola, Chad, Eritrea, Thailand, and Zimbabwe.

Medium contamination (5–19km²) is reported in seven States Parties: Colombia, Mauritania, Somalia, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Sudan, and Tajikistan.

Ten States Parties reported less than 5km² of contamination: Cyprus, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Ecuador, Guinea-Bissau, Niger, Oman, Palestine, Peru, Senegal, and Serbia.

Nigeria, which submitted a Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 extension request in 2021, reported that due to insecurity, the extent of contamination had not been determined. Nigeria is impacted by improvised mines, other improvised explosive devices (IEDs), and ERW, mainly in the states of Adamawa, Borno, and Yobe in the northeast.[19]

Estimated antipersonnel mine contamination in States Parties[20]

|

Region |

Massive (more than 100km²) |

Large (20–99km²) |

Medium (5–19km²) |

Small (less than 5km²) |

|

Americas |

Colombia |

Ecuador Peru |

||

|

East and South Asia and the Pacific |

Afghanistan Cambodia |

Thailand |

Sri Lanka |

|

|

Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia |

BiH Croatia Turkey Ukraine* |

Tajikistan |

Cyprus** Serbia

|

|

|

Middle East and North Africa |

Iraq Yemen |

Oman Palestine |

||

|

Sub-Saharan Africa |

Ethiopia* |

Angola Chad Eritrea Zimbabwe |

Mauritania Somalia South Sudan Sudan |

DRC Guinea-Bissau Niger Senegal |

*Both Ethiopia and Ukraine have reported massive contamination, although this cannot be reliably verified until survey has been conducted. It is expected that the estimates will be significantly reduced after survey. In Ukraine the estimate includes all contamination, including antipersonnel mines, antivehicle mines, and other ERW.

**Cyprus has stated that no areas contaminated by antipersonnel mines remain under its control.

- Americas

In December 2020, Colombia reported a total of 260 municipalities suspected or known to be contaminated, including 138 municipalities that were inaccessible or only partly accessible.[21] Contamination in accessible areas comprised 7.73km², with 1.85km² classified as confirmed hazardous areas (CHA) and 5.88km² as suspected hazardous areas (SHA).[22] Colombia also reported in December 2020 that 253 municipalities were free of contamination.[23]

Ecuador and Peru each have a very small amount of remaining contaminated area, of 0.04km² and 0.37km² respectively.[24]

- East and South Asia and the Pacific

As of the end of December 2020, Cambodia reported contamination of 801.64km², following the completion of a national baseline survey in 73 districts.[25] Thailand has a total of 62.95km² of contamination, of which 23.27km² are CHA (183 areas), and 39.68km² are SHA (43 areas). Much of the remaining contamination in Cambodia and Thailand is along their shared border, where access has been problematic due to a lack of border demarcation.[26]

Afghanistan reported contamination of 187.31km² as of the end of 2020, of which 148.46km² is classified as CHA, and 38.85km² is classified as SHA.[27] Prior to the Taliban taking control of Afghanistan in August 2021, new contamination resulting from fighting between the government and non-state armed groups (NSAGs) continued to add to the extent of contamination in the country.[28]

Mine contamination in Sri Lanka is mainly in Northern province, the scene of intense fighting during the civil war; and to a lesser extent in Eastern and North Central provinces. As of March 2021, Sri Lanka reported a total of 12.79km² contamination, with 304 CHA (11.44km²) and nine SHA (1.35km²).[29]

- Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia

BiH reported extensive contamination of 956.36km² as of the end of 2020.[30] The majority of hazardous areas in BiH are suspected rather than confirmed (95km² CHA and 861.36km2 SHA), meaning actual contamination may be less than reported.

As of March 2021, Croatia reported contamination of 279.55km² (196.89km² CHA, including 30.14km² under military control, and 82.66km² SHA) across eight of its 21 counties.[31] The majority of contaminated land in Croatia is reported to be in forested areas.[32] Newly discovered contamination was identified in four counties in 2020–2021.[33]

Turkey reported contamination of 145km² across 3,834 areas. The majority of contaminated areas are found along its borders with Armenia, Iran, Iraq, and Syria, while 920 areas are not in border regions.[34] Turkey plans to conduct non-technical survey during 2021–2023 of all of the contaminated areas, to provide a more accurate picture of contamination.[35]

Ukraine reported 7,000km² of contamination (undifferentiated, including antipersonnel mines) in government-controlled areas in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, as of the end of 2020.[36] Ukraine has provided the same estimate of contamination since 2018, and survey to provide a more accurate baseline has not yet been conducted.[37] In addition, an estimated 14,000km2 of undifferentiated contamination was reported in areas not controlled by the government.[38]

Cyprus, Serbia, and Tajikistan all have much smaller amounts of contamination.

Cyprus is believed to have 1.24km² of antipersonnel and antivehicle landmine contamination. However, the contamination is reported to be only in Turkish-controlled Northern Cyprus and in the buffer zone, and not in territory under the effective control of Cyprus.[39] Serbia reported 1.15km² of contamination across five areas, in Bujanovac municipality.[40] Tajikistan reported a total of 8.55km² of antipersonnel mine contamination (7.02km² CHA and 1.53km² SHA).[41]

- Middle East and North Africa

Iraq is dealing with contamination by improvised landmines in areas liberated from the Islamic State. As of the end of 2020, Iraq reported 1,199.95km² of antipersonnel mine contamination, and an additional 596.27km² of IED contamination, including improvised mines. The majority of contamination was in Federal Iraq.[42]

Yemen does not currently have a clear understanding of the level of contamination, as ongoing armed conflict continues to add to the extent and complexity of contamination, which includes improvised mines.[43] The scale of the conflict and its extensive impact has continued to prevent implementation of effective nationwide survey.[44] The most recent estimate of contamination, from March 2017, was 323km².[45]

Oman reported that all of its hazardous areas had been cleared before the signature of the Mine Ban Treaty, but were in the process of being “re-inspected” to deal with residual risk.[46]

Palestine reported 0.18km² of landmine contamination, of which 85,000m² was antipersonnel mines and 99,000m² was antivehicle mines.[47]

- Sub-Saharan Africa

Ethiopia reported in April 2020 that remaining contamination totaled 726.06km2, across 152 areas in six provinces.[48] Of this, 29 areas (3.52km²) were CHA, while 123 areas (722.54km²) were SHA.[49] Most SHAs are located in the Somali region. It believed that the baseline figure is an overestimate and that only 2% of these areas are actually likely to contain mines.[50]

As of December 2020, Angola reported total landmine contamination of 85.42km² across 17 provinces, of which 84.41km² was antipersonnel mines and 1.01km² was antivehicle mines. Of the antipersonnel mine contamination, 81.58km² was classified as CHA and 2.83km² as SHA.[51]

Chad has identified 147 hazardous areas across three provinces,[52] covering an estimated total of 80.33km² of mixed contamination (57.59km² CHAand 22.74km² SHA).[53] Over half of the mine contamination is located in Tibesti.[54] Lake province is contaminated with improvised mines.[55]

Eritrea has not reported on the extent of its contamination since 2014, when it was estimated at 33.5km².[56]

As of 31 December 2020, remaining mine contamination in Zimbabwe was 34.12km2. All of this contamination is classified as CHA, and is located in five provinces along the border with Mozambique and an inland minefield in Matabeleland North province.[57]

Mauritania declared clearance of all known contamination in 2018, but later identified further contamination.[58] A survey conducted in February and March 2021 identified 19 mined areas, covering 16.18km².[59] Local authorities have reported an additional mined area in Ouadane, in the Adrar region, the size of which is still to be determined.[60]

Somalia reported 6.1km² of antipersonnel mine contamination, out of a total of 161.8km² of mixed contamination which includes antivehicle mines.[61] Somalia also reported an increase in the use of improvised mines.[62] Since 2017, the Somali Explosives Management Authority (SEMA) reported it was in the process of synchronizing and verifying data in the national database, which may lead to adjustments to the figures.[63] This process was ongoing in 2021.

South Sudan reported 7.28km² of contamination as of 31 December 2020, with 63 areas classified as CHA (2.83km²) and 55 as SHA (4.45km²).[64] The largest SHA, in Jonglei, totaled 1.98km², but it is thought its size would be reduced through survey.

As of the end of 2020, Sudan reported 13.09km2 of antipersonnel mine contamination, with 56 CHA (up from 43 in 2019) and 41 SHA (down from 52 in 2019) across the states of Blue Nile, South Kordofan, and West Kordofan.[65] New contamination totaling 6.22km² was found in Blue Nile and South Kordofan in 2020, with 11 new hazardous areas registered.[66]

Contamination in the DRC totals 0.13km², but is partly located in the provinces of Ituri and North-Kivu, which are difficult to access due to the presence of NSAGs and the Ebola epidemic.[67]

In 2021, Guinea-Bissau reported that residual contamination covers 1.09km² and is classified as CHA, with antipersonnel mines accounting for 0.49km² and antivehicle mines accounting for 0.6km². In addition, 43 areas were suspected to contain both mines and ERW.[68]

Niger and Senegal both have small amounts of contamination. Senegal reported that following non-technical survey in 2020, 37 hazardous areas had been identified, covering 0.49km².[69] In 2020, Niger reported 0.18km² of CHA, adjacent to a military post in Madama, in the Agadez region.[70]

Suspected improvised antipersonnel mine contamination in States Parties with reported improvised mine hazards and casualties

Improvised devices designed to detonate—or which due to their design, can be detonated—by the presence, proximity, or contact of a person are prohibited under the Mine Ban Treaty.[71] Available information indicates that the fusing of most improvised landmines allows them to be activated by a person, but there may be exceptions.

Improvised mines are noted as a concern in the Oslo Action Plan, which says “the States Parties are also facing new challenges including increased use of anti-personnel mines of an improvised nature and rising number of victims.”

Action #21 of the Oslo Action Plan lays out the commitments of States Parties affected by improvised mines whereby all provisions and obligations of the treaty apply to such contamination. This includes the obligations to clear these devices in accordance with Article 5 and to provide regular information on the extent of contamination, disaggregated by type of mines, in their annual transparency reporting under Article 7.

Several States Parties suspected to be contaminated with improvised mines, which may be antipersonnel mines by their nature, have not declared clearance obligations under Article 5 or have not provided regular Article 7 transparency reports.

Improvised landmines causing casualties in Burkina Faso and Cameroon were believed to have primarily acted as de facto “antivehicle mines.” According to Monitor data for 2019, only vehicles were involved in mine incidents in both countries, and no casualties occurred while individuals were on foot. However, in 2020, a few incidents in Burkina Faso and Cameroon appear to have involved people walking.

In the following States Parties, casualties from improvised mines have been documented. These States Parties must clarify their status with regards to their Article 5 obligations and may need to request new clearance deadlines.

In Burkina Faso, IED use by NSAGs has been recorded since 2016. Pressure-plate improvised antivehicle mines have been increasingly used since 2018, due to the introduction of measures which block signals to command-detonated IEDs. In 2020, 107 casualties of improvised mines were recorded—although most incidents involved vehicles, including cars, carts, and bicycles. Yet in August 2020, eight children were killed by an improvised mine in Bembela. One report said the children were watching over animal herds when they stepped on an IED, while another said that the device exploded as some of the children were walking and some were on a cart.[72]

Cameroon originally declared that there were no mined areas under its jurisdiction and control, and its Article 5 deadline expired in 2013. However, since 2014, improvised mines have caused casualties, particularly in the north on the border with Nigeria, as Boko Haram’s activities have escalated.[73] The extent of contamination is unknown but is thought to be small. Most casualties in past years were traveling by vehicle; yet in 2020, of 12 improvised mine casualties, two were incidents that were reported to have occurred while the casualty was walking.[74]

Mali has confirmed antivehicle mine contamination, and since 2017 has experienced a significant increase in incidents caused by IEDs, including improvised mines, in the center of the country.[75] All casualties to date were traveling by vehicle. The Monitor recorded 242 improvised mine casualties in Mali in 2020. UNMAS reported to the Monitor that improvised mines in Mali are victim-activated by pressure tray or wire trap.[76]

Tunisia declared completion of clearance in 2009, but there have been reports of both civilian and military casualties from mines—including improvised mines—in the last five years.[77] The improvised mines causing casualties—particularly shepherds walking with their herds—often result in lower limb amputation, consistent with antipersonnel mine explosions.

Venezuela reported clearing all of its remaining mined areas under Article 5 in 2013.[78] Yet in August 2018, media reports said that Venezuelan military personnel suffered an antipersonnel mine incident in Catatumbo municipality, Zulia state, along the border with Colombia,[79] where Colombian NSAGs were believed to be using improvised mines to protect strategic positions.[80] In March 2021, the Venezuelan military engaged the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, FARC) in Victoria, in Apure state,[81] and a Venezuelan non-governmental organization (NGO) stated that mines “similar to those used in Colombia” were found in the area.[82] This indicates they were improvised antipersonnel mines. Contamination was later confirmed by a member of parliament and the Ministry of Defense.[83] Venezuela requested UN support to clear mines from the border in April 2021, and announced that the military would be using a mine sweeper prototype to clear the area.[84]

Antipersonnel mine contamination in states not party and other areas

Twenty-two states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty and five other areas have, or are believed to have, land contaminated by antipersonnel mines on their territories.

States not party and other areas with antipersonnel mine contamination

|

Abkhazia |

Israel |

Myanmar |

|

Armenia |

Korea (North) |

Nagorno-Karabakh |

|

Azerbaijan |

Korea (South) |

Pakistan |

|

China |

Kosovo |

Russia |

|

Cuba |

Kyrgyzstan |

Somaliland |

|

Egypt |

Lao PDR |

Syria |

|

Georgia |

Lebanon |

Uzbekistan |

|

India |

Libya |

Vietnam |

|

Iran |

Morocco |

Western Sahara |

Note: other areas are indicated in italics.

State not party Nepal and other area Taiwan have completed clearance of known mined areas since 1999.

States not party

The extent of contamination is unknown in most states not party: Armenia, China, Cuba, Egypt, India, Iran, Kyrgyzstan, Lao PDR, Libya, Morocco, Mynamar, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, South Korea, Syria, Uzbekistan, and Vietnam.

Landmines are known or suspected to be located along the borders of several states not party, including Armenia, China, Kyrgyzstan, Morocco, North Korea, South Korea, and Uzebkistan.

Ongoing conflict, insecurity, and the impact of improvised mines affect states not party Egypt, India, Libya, Myanmar, Pakistan, and Syria.

The level of contamination is known to some extent in Azerbaijan, Georgia, Israel, and Lebanon.

In Azerbaijan, contamination comprised 5km² of antipersonnel mine contamination (1.5km² CHA and 3.5km² SHA) and 8.71km² of antivehicle mine contamination (1.79km² CHA and 6.92km² SHA). Survey is needed to assess the extent of contamination, due to changes in control of parts of Nagorno-Karabakh after the conflict in 2020.[85]

In Georgia, contamination totaled 2.79km² across four mined areas, including 0.05km² contaminated with antipersonnel mines, and 2.74km² contaminated with antipersonnel mines and antivehicle mines. The size of two additional areas contaminated with antipersonnel mines, in the villages of Osiauri and Khojali, was unknown.[86]

Just over 90km² of contamination was reported in Israel in 2017, comprising 41.58km² CHA and 48.51km² SHA (including areas in the West Bank).[87] This did not include mined areas “deemed essential to Israel’s security.” No updates on contamination have been provided since 2017, although Israel reported progress in re-surveying mine affected areas and the clearance of 0.18km² in 2020.[88]

At the end of 2020, Lebanon reported 18.23km² of landmine contamination, all CHA. There was also 0.41km² of IED contamination, which included improvised mines.[89]

Other areas

Five other areas unable to accede to the Mine Ban Treaty due to their political status are known to have mine contamination: Abkhazia, Kosovo, Nagorno-Karabakh, Somaliland, and Western Sahara.

The extent of contamination in Abkhazia and Kosovo is small, at 0.01km² in Abkhazia and 1.2km² in Kosovo.[90]

Nagorno-Karabakh was reported to have 6.75km² of contaminated land including 5.62km² of antipersonnel mine contamination, 0.23km² of antivehicle mine contamination, and 0.9km² of mixed antipersonnel and antivehicle mine contamination.[91] The total extent of contamination may be subject to adjustment, due to changes in territorial control during the 2020 conflict and the possibility that new mines may have been laid.

Somaliland was reported to have 3.86km² of contaminated land in total, including 0.52km² of antipersonnel mine contamination, 2km² of antivehicle mine contamination, 0.17km² of ERW contamination, and 1.17km² of mixed contamination.[92]

Western Sahara has minefields east of the Berm,[93] covering an area of 215.96km² (90km² CHA and 125.96km² SHA).[94] According to the United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS), the minefields are contaminated with antivehicle mines, although small numbers of antipersonnel mines have been found in these areas.[95]

Landmines of all types—including antipersonnel mines, antivehicle mines, and improvised mines—as well as cluster munition remnants[96] and ERW remain a significant threat and continue to cause indiscriminate harm globally.

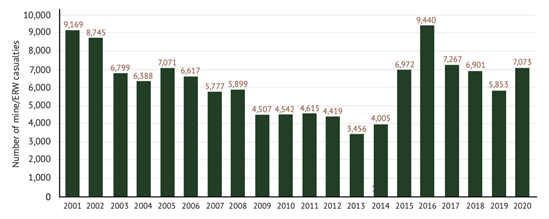

Following a sharp rise in casualties amid increased conflict and contamination since 2015, high numbers of casualties continued to be recorded in 2020, when at least 7,073 people were killed or injured by mines/ERW. Of that total, at least 2,492 were killed while 4,561 were injured. In the case of 20 casualties, it was not known if the person survived.[97]

Mine/ERW casualties were recorded in 51 countries and three other areas in 2020. The annual total represents an increase from 5,853 casualties in 2019, and an upward turn from three years of declining casualties (2017–2019) since the annual total reached a peak of 9,440 in 2016, due to increased conflict and the resulting contamination.[98]

States/areas with mine/ERW casualties in 2020

|

Region |

States and other areas |

||

|

Americas

|

Colombia |

||

|

East and South Asia and the Pacific

|

Afghanistan Bangladesh Cambodia India |

Lao PDR Myanmar Pakistan Philippines |

Solomon Islands Sri Lanka Thailand Vietnam |

|

Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia

|

Armenia Azerbaijan Croatia |

Nagorno-Karabakh Tajikistan Turkey |

Ukraine |

|

Middle East and North Africa

|

Algeria Egypt Iran Iraq Jordan |

Kuwait Lebanon Libya Morocco Palestine |

Syria Tunisia Yemen |

|

Sub-Saharan Africa

|

Angola Burkina Faso Cameroon Cent. African Rep. Chad Dem. Rep. Congo Ethiopia |

Kenya Mali Mauritania Mozambique Niger Nigeria Senegal |

Somalia Somaliland South Sudan Sudan Uganda Western Sahara Zimbabwe |

Note: States Parties are indicated in bold. Other areas are indicated in italics.

The casualty total for 2020 represents more than twice the number of casualties in 2013 (3,456), the year with the fewest mine/ERW casualties on record. The significant rise in casualties since that time is primarily due to intensive armed conflicts involving the use of improvised mines.

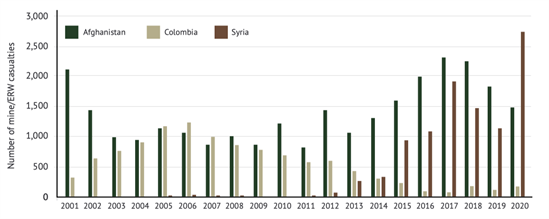

Mine/ERW casualties: 2001–2020[99]

Between 1999 and 2019, Afghanistan and Colombia alternated in having the highest number of annual recorded casualties. In 2020, Syria, a state not party to the Mine Ban Treaty, recorded the most casualties (2,729), followed by State Party Afghanistan (1,474). This marked the first year that Syria had the highest recorded number of annual casualties since Monitor reporting began in 1999. Afghanistan had recorded the most annual casualties each year from 2008–2019, while casualty rates in Colombia spiked from 2005–2007.

Mine/ERW casualties over 20 years in Afghanistan, Colombia, and Syria

The Monitor notes that since the Syrian Civil War began in 2011, casualty totals for Syria have fluctuated, due to inconsistent availability of data and sources and a lack of access to affected areas. Annual totals of recorded mine/ERW casualties in Syria are thought to be a considerable undercount, while ambiguity in the way that casualties and explosive incidents are reported in the media often leaves it unclear if mines involved in incidents were of an improvised nature. Casualty data for Syria is routinely adjusted in light of new surveys and historical data.

It is certain that many casualties go unrecorded each year globally, meaning not all casualties are captured in the Monitor’s data. Some countries do not have functional casualty surveillance systems in place, while other forms of reporting are often inadequate. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic posed an additional challenge to data collection efforts in mine/ERW affected countries.

InAfghanistan, data collection was limited amid ongoing conflict. The existing system records only civilian casualties. Reporting on military casualties is rare, with no data available for 2019 or 2020. Since May 2017, the Afghan military has stopped releasing conflict casualty figures.

The number of casualties in Azerbaijan in 2020 has not yet been adequately determined, in part due to the complexity of data collection following the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, but also due to changes in territorial control of affected areas. This risks duplication or under-reporting.[100]

Yemen reported that there was no nationwide casualty surveillance system, and that casualties were recorded in an ad hoc manner by local authorities, medical institutions, and the Yemen Executive Mine Action Center (YEMAC). The issue is compounded by the scale of the ongoing armed conflict in Yemen and the COVID-19 pandemic.[101] The Monitor recorded 350 casualties for Yemen in 2020. In its Article 7 report for 2020, Yemen reported 532 victims surveyed in 2020.[102] The UN Humanitarian Needs Overview for Yemen reported 1,300 civilians “affected in landmine or ERW related incidents” in 2020, with no reference to persons killed or injured.[103]

Casualty demographics[104]

Civilians accounted for the vast majority of mine/ERW casualties in 2020 compared to military and security forces.[105] In 2020, 80% of casualties were civilians, where their status was known, evidencing the long-recognized trend of civilian harm that motivated the adoption of the Mine Ban Treaty. The Monitor identified 27 casualties among deminers in nine countries during 2020 while the remaining 20% of casualties were military or combatants. The country with the most military casualties was Syria (390), followed by Mali (165), Ukraine (120), and Nigeria (113).

Civilian status of casualties in 2020

|

Civilian |

4,437 |

|

Deminer |

27 |

|

Military |

1,105 |

|

Unknown |

1,504 |

There were at least 1,872 child casualties in 2020. Children made up half of civilian casualties where the age group was known (3,733), and accounted for 30% of all casualties for whom the age group was known (6,272).[106] Children were killed (645) or injured (1,218) by mines/ERW in 34 states and one other area in 2020.[107]

In 2020, as in previous years, the vast majority of child casualties—where the sex was known—were boys (81%).[108] ERW was the device type that caused most child casualties (870, or 46%), followed by improvised mines (434, or 23%).

In 2020, as in past years, men and boys made up the majority of casualties, accounting for 85% of all casualties where the sex was known (4,583 of 5,388). Women and girls made up 15% of all casualties where the sex was known (807).

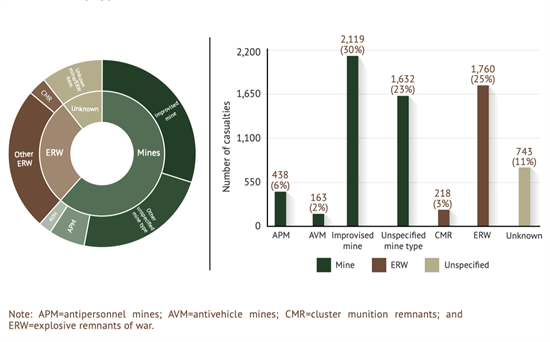

Casualties by device type

Countries with high and increasing numbers of casualties are mostly those with improvised mine casualties. In 2020, improvised mines accounted for the highest number of casualties (2,119) for the fifth year in a row. Although the number of casualties attributed to improvised mines declined from 2019, this is attributable to variants in casualty recording terminology. Most casualties attributed to unspecified mine types in 2020 were reported in countries with improvised mine casualties (1,550 of 1,632 unspecified mine casualties in 2020, or 95%).[109]

Casualties by type of mine/ERW in 2020

In 2020, landmines caused at least 4,352 casualties, including those reported as factory-made antipersonnel mines, improvised mines, antivehicle mines, and unspecified mines.[110]

Cluster munition remnants caused 218 casualties,[111] while other ERW caused 1,760 casualties.[112]

A total of 743 casualties were the result of mine/ERW items that were not disaggregated in data or reporting.[113]

Casualties and Mine Ban Treaty status in 2020

Mine/ERW casualties occurred in 38 States Parties in 2020.[114] States Parties accounted for half (52%, or 3,642) of annual casualties. Eight States Parties recorded more than 100 casualties in 2020: Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Colombia, Iraq, Mali, Nigeria, Ukraine, and Yemen.

States Parties with over 100 casualties in 2020

|

State Party |

Casualties |

|

Afghanistan |

1,474 |

|

Mali |

368 |

|

Yemen |

350 |

|

Ukraine |

277 |

|

Nigeria |

226 |

|

Colombia |

167 |

|

Iraq |

167 |

|

Burkina Faso |

111 |

There is a clear trend of declining annual casualties in most States Parties since the Mine Ban Treaty came into existence more than 20 years ago, with the exception of those experiencing conflict and substantial improvised mine use.

In 2020, the Monitor identified 3,391 mine/ERW casualties in 12 states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty.[115] More than 80% of those casualties were recorded in Syria (2,729).[116] Myanmar accounted for the next highest total among countries yet to join the treaty, with 280 casualties.

In three other areas—Nagorno-Karabakh, Somaliland, and Western Sahara—a combined total of 37 casualties were reported in 2020.[117]

The Oslo Action Plan, agreed in November 2019 at the Fourth Review Conference of the Mine Ban Treaty, highlights best practices that contribute to the effective implementation of mine action programs. These include high levels of national ownership; developing evidence-based, costed, and time-bound national strategies and workplans; and keeping national mine action standards up to date with the latest International Mine Action Standards (IMAS).

Click here to see a summary table of mine action management and coordination

In 2020, clearance in most States Parties with contamination was managed and coordinated through national mine action centers. This was the case in Afghanistan, Angola, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Cambodia, Chad, Chile, Colombia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Ecuador, Iraq, Mauritania, Niger, Palestine, Peru, Senegal, Serbia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkey, Ukraine, Yemen, and Zimbabwe.

Guinea-Bissau’s National Mine Action Coordination Center (Centro Nacional de Coordenação da Acção Anti-Minas, CAAMI), formed in 2001, and under the responsibility of the Ministry of Defense since 2009, had been inactive since 2012.[118] Having submitted a Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline extension request in 2021, CAAMI reported that a new director had been appointed and that it had resumed activities.[119]

Nigeria formed an Inter-Ministerial Committee in 2019 to develop a mine action strategy and a workplan for survey and clearance.[120] In its 2021 Article 5 deadline extension request, Nigeria reported that it hoped to establish a national mine action center during the extension period.[121]

In Ukraine, a new structure comprising a National Mine Action Authority (NMAA) chaired by the Minister of Defense, and two mine action centers—one under the Ministry of Defense and one under the Ministry of Internal Affairs’ State Emergency Service of Ukraine (SESU)—were approved in September 2020 via an amendment to the 2018 Mine Action law.[122] The two mine action centers were established and undergoing accreditation and staffing as of August 2021.[123]

National mine action strategies

National mine action strategies and workplans are crucial for strengthening national ownership of mine action programs, and to enable greater transparency and accountability via monitoring and reporting of progress on clearance under Article 5. Developing a national strategy and workplans can also help states align their mine action activities with broader humanitarian and development aims, and boost their ability to secure international funding.

In 2020, 23 States Parties reported having national mine action strategies and/or workplans in place. Afghanistan, Croatia, Iraq, Sudan, and Tajikistan were in the process of updating their national strategies in 2020, with the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) supporting the process in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Sudan.[124]

Sri Lanka planned to update its national strategy in 2021, based on the results of ongoing re-survey in Northern, Eastern, and North Central provinces.[125] The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) planned to assist Yemen in updating its outdated national strategy in 2021, to better reflect mine action needs and priorities amid the ongoing conflict.[126]

In 2020, States Parties Cyprus, the DRC, Eritrea, Guinea-Bissau, Niger, Nigeria, Oman, Serbia, and Ukraine did not have national mine action strategies in place. The DRC’s strategy expired in 2019, though it reported in August 2020 and again in February 2021 that it was in the process of developing a new strategy.[127] The GICHD planned to work with Ukraine to develop a national mine action strategy, with a workshop due to be held in 2022.[128]

Information management

States Parties that did not use the Information Management System for Mine Action (IMSMA) in 2020 included BiH, Croatia, Eritrea, Niger, Oman, Thailand, and Serbia. Serbia was in contact with GICHD to discuss the possibility of installing IMSMA.[129]

As part of the UNDP Mine Action Governance and Management Project, which began in 2017 and is funded by the European Union (EU), the BiH Mine Action Centre (BHMAC) planned to create a new online database to increase the availability and transparency of its mine action data.[130] Colombia also enhanced its reporting and monitoring via interactive digital dashboards on demining, risk education, and victim assistance. These dashboards and mine action datasets have been made publicly accessible through the Comprehensive Action against Antipersonnel Mines (Acción Integral Contra Minas Antipersonales, AICMA) online “geoportal”.[131]

Ukraine had two functioning IMSMA databases in 2020, one managed by SESU and the other by the Ministry of Defense. Consolidation of both databases into a central national IMSMA database is planned once the NMAA has been established.[132]

Transparency reporting

As of 1 October 2021, seven States Parties with clearance obligations had not yet submitted Article 7 transparency reports for calendar year 2020: the DRC, Eritrea, Guinea-Bissau, Niger, Nigeria, Palestine, and Somalia.

Four of them have not submitted their report for many years: Niger since 2018, Eritrea since 2014, Nigeria since 2012, and Guinea-Bissau since 2011.[133] In line with Action #49 of the Oslo Action Plan, States Parties that have provided no update on implementation of their clearance obligations under Article 5 for two consecutive years should be assisted by the president of the Mine Ban Treaty, in close cooperation with the Article 5 Committee.

National mine action standards

Several States Parties reported updating national mine action standards in 2020:

- Afghanistan updated standards on improvised mines, planning and prioritization, and quality management;[134]

- Angola updated standards on land release, accreditation, training, technical and non-technical survey, post-clearance documentation, and quality and information management;[135]

- Cambodia updated standards on land release, accreditation, and quality and information management;[136] and

- Colombia updated standards on land release and information management.[137]

In 2020, Iraq, Thailand, Yemen, and Zimbabwe all reported that their national standards were in the process of being reviewed and updated.[138] A national standards workshop in Yemen, set to take place in April 2020, was postponed amid the COVID-19 pandemic, but work began in September 2020 to update survey standards. Yemen reported that the Arabic version was 95% complete as of the end of 2020.[139]

Ukraine’s national mine action standards, first published in April 2019, were being revised in 2021 and will become binding after the establishment of the NMAA.[140]

Some States Parties need to update their national standards, or are still waiting for standards to be approved. Mauritania is required to update its national mine action standards, which date to 2007, and is planning to review them during its fourth extension period.[141] Somalia completed revision of its national standards in 2019, and prepared them for approval by the Ministry of Internal Security in 2020 after receiving feedback from stakeholders.[142] As of September 2021, the National Technical Standards and Guidelines in Somalia were still pending approval.[143]

In 2020, the Mine Action Programme of Afghanistan (MAPA) and the Directorate of Mine Action (DMA) in Iraq reported developing guidelines for the conduct of mine action operations in the context of COVID-19 prevention measures.[144]

In 2020, 15 States Parties had mechanisms for coordinating risk education, either through specific risk education technical working group meetings, or through inclusion in meetings of the United Nations (UN) Mine Action Sub-Cluster. Seventeen States Parties reported no specific mechanisms for risk education coordination.

In Croatia, risk education is coordinated at the regional level, through five large area offices and 15 smaller branch offices of the National Education Center for Civil Protection.[145] The Somali Explosives Management Authority (SEMA) coordinates risk education in Somalia via consortiums of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in each state.[146]

In Sri Lanka, there is no official coordination mechanism, but the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) works with the national mine action center to support risk education activities conducted in schools through the Ministry of Education, and at community level through local NGOs.[147]

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic limited risk education coordination meetings in some States Parties. In Cambodia, the Risk Education Technical Reference Group, which usually meets on a quarterly basis, met once in 2020.[148] In Iraq, the risk education working group held only one face-to-face meeting.[149] In South Sudan, risk education meetings were conducted online, but due to limited internet connection some agencies were unable to attend.[150]

Risk education delivery amid COVID-19 restrictions was a key topic of meetings in 2020.

Strategies and national standards

In 2020, risk education was included within the national mine action strategies of States Parties Afghanistan, Angola, BiH, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, Croatia, Iraq, Senegal, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, and Thailand. In addition, Ethiopia and Turkey reported including risk education in their national mine action workplans.

Cambodia and Somalia updated their national standards on risk education in line with IMAS 12.10 on Explosive Ordnance Risk Education (EORE), revised in November 2020.[151] Risk education standards in Somalia were still pending approval as of September 2021. Colombia updated Standard Operating Procedures for risk education to align with the updated IMAS.[152]

Iraq and Thailand were also in the process of updating national risk education standards in line with the revised IMAS 12.10.[153]

Several States Parties had no risk education standards, or had standards that required updating. Angola had no risk education standards, but Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA) planned to support the National Intersectoral Commission for Demining and Humanitarian Assistance (Comissão Nacional Intersectorial de Desminagem e Assistência Humanitária, CNIDAH) to develop these as part of its capacity development support.[154] Chad had reported that it would review its risk education standards at the end of 2020,[155] but in 2021 said this would take place in 2022.[156] In Yemen, national standards were reported to be in the early stages of development.[157]

Transparency reporting

Action #29 of the Oslo Action Plan requires States Parties to report on risk education and other risk reduction programs in their Article 7 reports, including on methodologies used, challenges faced, and the results achieved; with information disaggregated by gender, age, and disability.

As of 1 October 2021, 20 of the 26 mine-affected States Parties that had submitted their Article 7 reports for calendar year 2020 reported on risk education. However, the level of detail varied. Afghanistan, Cambodia, Colombia, Iraq, South Sudan, Sudan, and Thailand all provided risk education beneficiary data disaggregated by age and sex, and also provided details of their risk education programs, including on activities, methodologies, and challenges amid COVID-19.

Eleven States Parties provided a description of risk education activities but no beneficiary data: BiH, Croatia, Ecuador, Ethiopia, Mauritania, Peru, Senegal, Serbia, Sri Lanka, Turkey, and Zimbabwe. In some cases—such as Peru, Senegal, and Turkey—no activities were conducted, due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

States parties Angola and Yemen provided only beneficiary data, although it was disaggregated by age and sex. States Parties Chad, Cyprus, Oman, Tajikistan, and Ukraine did not report on risk education activities in their Article 7 reports.

No States Parties reported reaching persons with disabilities through risk education in 2020.

Risk education in Article 5 deadline extension requests

Action #24 of the Oslo Action Plan states that extension requests under Article 5 should include detailed, costed, and multiyear plans for context-specific mine risk education and reduction in affected communities. This will help ensure that risk education programs are planned, budgeted, and integrated within the overall obligations of States Parties.

In 2020, BiH, Colombia, the DRC, Mauritania, and Senegal described risk education activities within their Article 5 extension requests, though did not provide costed and detailed multiyear plans. Only South Sudan provided a clear explanation of risk education plans and a budget in its extension request. Niger and Ukraine did not include risk education in their requests.

In 2021, the DRC, Mauritania, Nigeria, Somalia, and Turkey all included some mention of risk education within their extension requests, though none provided costed and detailed multiyear plans. Cyprus, Guinea-Bissau, and Nigeria did not include risk education in their requests.

Victim assistance coordination

States Parties with significant numbers of victims and needs[158]

|

Afghanistan |

El Salvador |

Serbia |

|

Albania |

Eritrea |

Somalia |

|

Algeria |

Ethiopia |

South Sudan |

|

Angola |

Guinea-Bissau |

Sri Lanka |

|

BiH |

Iraq |

Sudan |

|

Burundi |

Jordan |

Tajikistan |

|

Cambodia |

Mozambique |

Thailand |

|

Chad |

Nicaragua |

Turkey |

|

Colombia |

Palestine |

Uganda |

|

Croatia |

Peru |

Ukraine |

|

Dem. Rep. Congo |

Senegal |

Yemen |

States Parties which have a responsibility for victims

The Oslo Action Plan reaffirms the commitment of States Parties to “ensuring the full, equal and effective participation of mine victims in society, based on respect for human rights, gender equality and non-discrimination.”

At the First Review Conference of the Mine Ban Treaty, held in Nairobi in 2004, States Parties “indicated there likely are hundreds, thousands or tens-of-thousands of landmine survivors,” and that states with victims had the greatest responsibility to act, but also the greatest need and expectations for assistance. The Monitor’s reporting on victim assistance focuses primarily on the States Parties in which there are significant numbers of victims and needs for assistance.

A definition of “landmine victim” was agreed by States Parties at the First Review Conference, as “those who either individually or collectively have suffered physical or psychological injury, economic loss or substantial impairment of their fundamental rights through acts or omissions related to mine utilization.”[159] Landmine victim, according to this widely accepted understanding of the term, includes survivors, as well as affected families and communities. [160]

Participation of victims and their representative organizations

Participation of victims is an overarching principle in the Oslo Action Plan.[161] In 2020, victims were reported to be represented in coordination in Afghanistan, Angola, BiH, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Iraq, Jordan, Mozambique, Peru, South Sudan, Sudan, Tajikistan, and Thailand. Victim participation in coordination activities was lower than in past years, partly due to COVID-19 restrictions.

There were few indications that input from victims was acted upon in 2020. Reporting by states lacked detail on processes for including inputs from victims in decision-making. However, in February 2021, Colombia hosted a three-day meeting in Bogota, aimed at ensuring inclusion of victims from different backgrounds and regions.[162]

Victim assistance standards

The process to adopt a first specific IMAS on victim assistance began in 2018. Following a review of an initial draft that was made available in 2020, the new standard was fully adopted in October 2021.[163] According to the IMAS 13.10 on Victim Assistance, national mine action authorities and centers can, and should, play a role in monitoring and facilitating the ongoing, multi-sector efforts to address the needs of survivors, and help in ensuring the inclusion of survivors and indirect victims, and their views in the development of relevant national legislation and policy decisions. The standard notes that national mine action authorities are well placed to gather data on victims and needs, provide information on services, and refer victims for support.[164]

Afghanistan and Cambodia reported on their participation in the development of the IMAS on victim assistance. In 2020, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and Humanity & Inclusion (HI) held meetings with DMA in Iraq, on preparing a national standard for victim assistance and developing a mechanism for the collection of standardized victim data.[165]

A relevant government agency to coordinate victim assistance[166]

Twenty-one States Parties were reported to have victim assistance coordination linked to disability coordination mechanisms that considered issues related to the needs of mine/ERW victims.

Due to COVID-19 restrictions, no victim assistance coordination meetings were held in BiH, Chad, or the DRC in 2020.

Multi-sectoral efforts in line with the CRPD[167]

Adopting, and implementing, a comprehensive plan of action that identifies gaps and aims to fulfill the rights and needs of victims—and, or among, persons with disabilities—is a key step toward ensuring a coordinated response to the needs of mine victims in each State Party.

The Oslo Action plan confirms that States Parties “recognize the need to integrate assistance to victims and survivors into broader national policies, plans and legal frameworks relating to the rights of persons with disabilities, health, education, employment, development and poverty reduction.”[168]

In Afghanistan, the National Disability Strategy 2030 had been deposited with the president in 2020 for adoption, and some 15 action plans for its implementation were developed. The draft strategy was last discussed at the Ministry of Martyrs and Disabled in June 2021.[169]

Centralized database with needs and challenges[170]

The Oslo Action Plan calls for States Parties to use a centralized database including information on persons killed and injured, and the needs and challenges of mine survivors—disaggregated by gender, age, and disability to ensure a comprehensive response. Progress in the development of centralized databases since the adoption of the Oslo Action Plan in 2019 has been unsteady.

Afghanistan’s National Disability Database was under development in 2020, in which 370,000 martyrs and persons with disabilities will be registered through a biometric system.[171] People with a disability acquired due to conflict are prioritized and will make up most beneficiaries.[172] Initial registration took place in Kabul and four other provinces in 2019.[173] In September 2021, concerns were raised that biometric data collected by the deposed Afghan government, and inherited by the Taliban, could be used to identify people linked to previous regimes or international forces, or members of persecuted groups who have received aid.[174]

In Iraq, DMA worked with the Ministry of Health and Environment and the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs in 2020, to develop a database for persons with disabilities and mine/ERW victims.[175] Discussions were held between DMA, ICRC, and HI regarding the mechanism for collecting victim data.[176]

Data collection on the needs of mine/ERW victims in Cambodia, Colombia, and Thailand was ongoing in 2020.

Croatia’s development of a unified database on mine/ERW victim needs has stalled since 2017. In 2020, data on mine victims and their family members was collected for inclusion in a central mine/ERW victim database, as part of a mine action project funded by Switzerland.[177]

Somalia, Ukraine, and Yemen needed to significantly improve the collection of victim data and each establish a unified and coordinated system.

National referral mechanisms[178]

States Parties can improve accessibility for victims by ensuring that service providers have the capacity to make referrals to appropriate health and rehabilitation facilities. Some victims may need to be referred to specialized services,from one health facility to another, or for travel and treatment abroad. Referral mechanisms can involve national systems as well as local networks, including referral via community-based rehabilitation systems.

National mine action centers that reported referring survivors to access services included those in BiH, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, Iraq, Tajikistan, Thailand, and Yemen.

National government ministries and bodies provided referrals as victim assistance focal points in Algeria, Angola, Colombia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Nicaragua, and Peru.

Many NGOs provided referrals at the national or local level in the States Parties with victims. These groups included survivor networks, disabled persons’ organizations (DPOs, also referred to as organizations of persons with disabilities, OPDs), national NGOs, and international NGOs such as HI, ICRC, and national Red Cross and Red Crescent movements.

The list of States Parties with significant numbers of victims and needs does not encompass all States Parties with responsibility for mine survivors. The actions contained in the Oslo Action Plan are specifically aimed at States Parties with a significant number of victims, yet the victim assistance section also notes more broadly that “States Parties with victims in areas under their jurisdiction or control will endeavour to do their utmost to provide appropriate, affordable and accessible services to mine victims, on an equal basis with others.”

States Parties where the number of survivors reported or estimated is more than 100 (including those recognized as having a significant number of victims) can be found in the table below.

States Parties with more than 100 mine/ERW survivors

|

More than 20,000 survivors |

Between 5,000 and 20,000 survivors |

Between 1,000 and 4,999 survivors |

Between 100–999 survivors |

|

Afghanistan Cambodia Iraq |

Angola BiH Colombia Ethiopia Mozambique Sri Lanka Turkey

|

Algeria Belarus Burundi Chad Croatia Dem. Rep. Congo El Salvador Eritrea Guinea-Bissau Kenya Kuwait Nicaragua Palestine Serbia Somalia South Sudan Sudan Thailand Uganda Ukraine Yemen Zimbabwe |

Albania Bangladesh Chile Honduras Jordan Mali Montenegro Namibia Niger Nigeria Peru Philippines Rwanda Senegal Tajikistan Zambia |

Mine clearance in 2020

The Mine Ban Treaty obligates each State Party to destroy or ensure the destruction of all anti-personnel landmines in mined areas under their jurisdiction or control, as soon as possible, but not later than 10 years after the entry into force of the treaty for that State Party.

Among States Parties, total reported clearance in 2020 was at least 146km².[179] This represents a decrease from the reported 156km² cleared in 2019. At least 135,583 landmines were cleared and destroyed in 2020.

Monitor data on mine clearance in States Parties is based on analysis of information provided by multiple sources, including reporting by national mine action programs, Article 7 reports, and Article 5 extension requests. In cases where varying annual figures are reported by States Parties, details are provided in footnotes and more information can be found in country profiles on the Monitor website.

Antipersonnel mine clearance in 2019–2020[180]

|

State Party |

2019 |

2020 |

||

|

Clearance (km²) |

APM destroyed |

Clearance (km²) |

APM destroyed |

|

|

Afghanistan |

28.01 |

7,801 |

24.24 |

5,379 |

|

Angola |

1.92 |

1,943 |

1.77 |

452 |

|

Argentina* |

See clearance figures under UK |

|||

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) |

0.53 |

963 |

0.29 |

1,357 |

|

Cambodia |

20.93 |

15,425 |

46.42 |

10,085 |

|

Chad |

0.47 |

0 |

0.21 |

39 |

|

Chile |

0.55 |

4,093 |

0.60 |

12,526 |

|

Colombia |

0.79 |

311 |

1.08 |

166 |

|

Croatia |

39.16 |

2,530 |

49.66 |

4,953 |

|

Cyprus** |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Dem. Rep. Congo |

0.21 |

26 |

0.02 |

23 |

|

Ecuador |

0.002 |

62 |

0 |

0 |

|

Eritrea |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

|

Ethiopia |

1.75 |

128 |

0 |

0 |

|

Guinea-Bissau |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

|

Iraq |

46.56 |

12,378 |

7.66 |

4,043 |

|

Mali |

N/R |

8 |

N/R |

5 |

|

Mauritania |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Niger |

0.01 |

208 |

0.01 |

115 |

|

Nigeria |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

|

Oman |

0.13 |

0 |

0.23 |

0 |

|

Palestine |

0.01 |

106 |

0.01 |

16 |

|

Peru |

0.08 |

1,113 |

0 |

0 |

|

Senegal |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Serbia |

0.60 |

22 |

0.27 |

0 |

|

Somalia |

0.12 |

6 |

0.77*** |

1 |

|

South Sudan |

1 |

405 |

0.71 |

246 |

|

Sri Lanka |

N/R |

N/R |

4.59 |

43,157 |

|

Sudan |

0.87 |

1 |

0.35 |

42 |

|

Tajikistan |

0.53 |

5,219 |

0.65 |

5,106 |

|

Thailand |

0.09 |

2,677 |

0.92 |

9,355 |

|

Turkey |

0.67 |

25,959 |

0.14 |

9,781 |

|

Ukraine |

1.70 |

N/R |

N/R |

5 |

|

United Kingdom (UK)* |

3.61 |

319 |

0.23 |

432 |

|

Yemen |

3.10 |

1,536 |

2.80*** |

1,388 |

|

Zimbabwe |

2.75 |

39,031 |

2.41 |

26,911 |

|

Total |

156.15 |

122,270 |

146.04 |

135,583 |

Note: N/R=not reported; APM=antipersonnel mines.

*Argentina and the UK both claim sovereignty over the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas.

**Cyprus states that no areas contaminated by antipersonnel mines remain under Cypriot control.

***Clearance of mixed, undifferentiated contamination that included antipersonnel mines.

Several States Parties reported that the COVID-19 pandemic presented challenges to demining operations in 2020. Angola, Chad, Senegal, Serbia, South Sudan, and Zimbabwe all suspended demining operations for a period to comply with national measures to counter the pandemic.[181] Angola reported that movement restrictions impacted the supply chain, and Tajikistan reported that border closures delayed the delivery of demining equipment and supplies.[182] In other states, including Afghanistan, Cambodia, Sudan, and Thailand, clearance operations continued, albeit with precautionary measures in place.[183] However, in States Parties Ecuador, Ethiopia, Peru, and Senegal, demining operations were largely suspended during 2020.

Despite the restrictions and challenges created by the COVID-19 pandemic, some States Parties maintained a steady clearance output in 2020. Based on reported data, Croatia cleared the most land during 2020 (49.66km²), closely followed by Cambodia (46.42km²). Cambodia cleared and destroyed 10,085 antipersonnel mines, compared to 4,953 in Croatia. Sri Lanka cleared and destroyed the most landmines in 2020, reporting 43,157 mines cleared from 4.59km².

Afghanistan cleared 24.24km², down from 28.01km² cleared in 2019. The Directorate of Mine Action Coordination (DMAC) in Afghanistan told the Monitor that while it had met its original baseline land release target—set in its 2013 extension request—annual land release targets had increased each year, due to both legacy and new contamination being added to the database. In 2020, Afghanistan reported that it had reached only about 34% of the annual target.[184]

Mine action in Yemen continued to operate under emergency response conditions in 2020, with a fire brigade approach to clearance focused on small, high-threat areas, with significant impact for communities.[185] In 2020, non-technical survey was being planned and is expected to start in 2021. It aims to establish a baseline to enable the planning of future clearance.[186]

Afghanistan, BiH, Colombia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Iraq, and Yemen reported clearing improvised mines as well as antipersonnel mines in 2020. In its Article 7 transparency report, Iraq provided better disaggregated data for land cleared of improvised mines as opposed to all improvised explosive devices (IED), hence reducing the amount of land reported cleared in 2020 compared to 2019. The United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS) reported the clearance of improvised mines in Mali.[187]

Chile and the United Kingdom (UK) met their Article 5 clearance obligations in 2020. Chile completed clearance on 27 February 2020 after releasing 2.69km² in the first two months of the year, of which 0.6km² was cleared. Chile reported that 12,526 antipersonnel mines and 10,170 antivehicle mines were cleared during this two-month period.[188] The UK reported completing clearance of antipersonnel landmines in the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas in November 2020, having cleared four remaining contaminated areas in the Yorke Bay area, totaling 0.23km².[189] The UK reported clearing and destroying 432 mines in 2020.[190]

Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Chad, the DRC, Niger, Oman, Palestine, Serbia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, and Turkey all cleared under 1km² in 2020.[191] Five of these States Parties—the DRC, Niger, Oman, Palestine, and Serbia—have small amounts of contamination while four—Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, and Tajikistan—have contamination classified as medium, and therefore should be able to complete clearance within the next few years if clearance and land release outputs are increased. Niger also reported no clearance since the beginning of March 2020. Oman reported “re-clearance” of 0.23km² in 2020 and 0.13km² in 2019, but no landmines were found and destroyed.[192] Serbia cleared no antipersonnel mines during 2020, but reported clearing one antivehicle mine and 1,586 ERW.[193]

Ukraine did not report mine clearance in its Article 7 report for 2020. The State Emergency Service of Ukraine (SESU) reported clearing 49.39km² and destroying 73,375 ERW, although it did not specify clearance of antipersonnel mines.[194] International operators cleared just over 2km² of undifferentiated contaminated land in Ukraine, destroying five antipersonnel mines.[195]

Five States Parties reported no clearance during 2020: Cyprus, Ecuador, Mauritania, Peru, and Senegal. Cyprus did not undertake clearance, as no areas contaminated by antipersonnel mines remained under its control.[196] Ecuador and Peru both reported that clearance operations were suspended amid the COVID-19 pandemic.[197] Mauritania reported conducting survey to confirm newly identified contaminated areas.[198] Senegal reported that an action plan for resource mobilization had been developed and that non-technical survey had begun, but no suspicious areas had been identified. Implementation in Senegal was suspended due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[199] Senegal has not reported any clearance since 2017.

Ethiopia reported in its Article 7 report for 2020 that it had cleared 1.75km² of land, and cleared and destroyed 128 mines.[200] These were the same figures provided in its Article 7 report for 2019 which covered the period January 2019–April 2020.[201] It is likely that Ethiopia did not conduct further clearance after April 2020.

Article 5 deadlines and extension requests

If a State Party believes that it will be unable to clear and destroy all antipersonnel landmines contaminating its territory within 10 years after entry into force of the Mine Ban Treaty for the country, it is able to request an extension for a period of up to 10 years.

Progress to 2025

At the Third Review Conference of the Mine Ban Treaty in Maputo, in June 2014, States Parties agreed to “intensify their efforts to complete their respective time-bound obligations with the urgency that the completion work requires.” This included a commitment “to clear all mined areas as soon as possible, to the fullest extent by 2025.”

As of 30 September 2021, 24 States Parties had deadlines to meet their Article 5 obligations before and no later than 2025.

Seven States Parties have Article 5 deadlines later than 2025: BiH (2027), Croatia (2026), Iraq (2028), Palestine (2028), Senegal (2026), South Sudan (2026), and Sri Lanka (2028).

Of the seven Article 5 extension requests submitted in 2021, five States Parties have requested extensions up to 2025, while two States Parties have requested extensions beyond 2025.

Despite the majority of States Parties having deadlines in 2025 or earlier, it appears that few of these States Parties will meet their deadlines.

In several States Parties, land release projections are behind target, which they reported was due to a lack of funding and demining capacity.

In 2019 and 2020, Angola failed to meet its projection for land release of 17km² per year, and has not provided an updated workplan or adjusted milestones.[202] Cambodia reported requiring additional financial support and demining capacity to meet its 2025 deadline.[203] Tajikistan also reported that its current capacity would need to be increased to meet its extension deadline.[204] Chad indicated to the Monitor that it is uncertain whether it will meet its deadline, due to funding uncertainties beyond September 2021.[205] Serbia also reported a lack of funding for field operations, which prevented survey of suspected contaminated areas in 2020.[206] Serbia’s annual clearance figure of 0.27km² was just below its projected clearance target of 0.3km².

Several States Parties reported that the COVID-19 pandemic had compromised progress.

Demining operations in Ecuador were suspended in 2020. The pandemic was reported to have delayed planning and affected Ecuador’s ability to complete clearance by 2022.[207] Ecuador has cleared 0.55km² of antipersonnel mine contaminated land since demining operations began in 2000.[208] Ethiopia reported that most field activities in 2020 were suspended amid the pandemic, affecting land release in the Somali region. Ethiopia did not meet its annual clearance target.[209] Peru’s land release output had increased significantly in 2019. However, in 2020, the pandemic prevented clearance operations.[210] Sudan reported that it was not on target to meet its deadline of April 2023, claiming that two years of progress were lost due to political instability and the pandemic.[211]

Thailand—which was on target in terms of its survey and clearance plan—reported that it was uncertain whether its deadline would be met, as COVID-19 restrictions had prevented face-to-face meetings with Cambodia to negotiate border clearance. The Thailand Mine Action Center (TMAC) was concerned that the national mine clearance budget may also be reduced as a result of the pandemic.[212] Zimbabwe, also on target to meet its deadline, noted that the pandemic and the national economic situation could impact its ability to meet its 2025 deadline.[213]

Afghanistan, Ukraine, and Yemen are each unlikely to meet their deadlines before 2025 due to insecurity, conflict, and the extent of contamination.

Afghanistan reported that it will not meet its 2023 deadline due to decreased funding, the need for survey of legacy contamination, and new contamination by improvised mines. Afghanistan anticipated submitting an extension request for at least five additional years until 2028.[214] The Taliban takeover in August 2021 has created uncertainty about the continued progress of mine clearance in Afghanistan.

In Ukraine, ongoing conflict means it is unlikely to meet its Article 5 deadline.[215] In June 2020, Ukraine stated that it did not have control over territories in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, impeding its ability to clear contaminated areas in these territories, and that the hostilities were causing further contamination along the contact line.[216]