Cluster Munition Monitor 2015

Ban Policy Overview

Slovakia, a past producer and exporter of cluster munitions, submits its accession instrument to become the 93rd State Party to the Convention on Cluster Munitions.

©UN Treaty Collection, August 2015

Cluster Munition Ban Policy

Introduction | Universalization | Use | Production | Transfer | Stockpiles | Retention | Transparency Reporting | National Implemenation Legislation | Interpretive Issues

The Convention on Cluster Munitions provides a comprehensive framework to eradicate cluster munitions and thereby put an end to the suffering caused by these weapons.

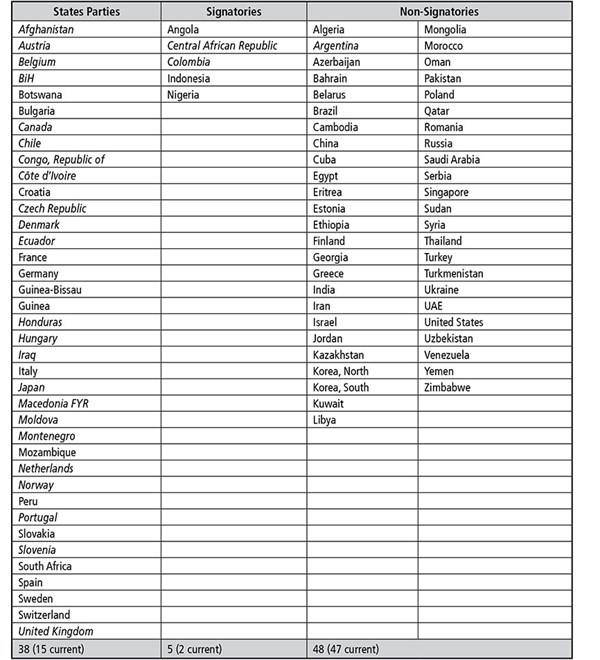

The 117 states that have signed, ratified, or acceded to the convention are its success story.[1] Spurred on by the United Nations (UN), International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), and the Cluster Munition Coalition (CMC), these states are adhering to the convention’s absolute prohibition on the use, production, transfer, and stockpiling of cluster munitions and are working to destroy their stocks, clear land contaminated by cluster munition remnants, and assist victims of the weapons.

When the Convention on Cluster Munitions entered into force on 1 August 2010, becoming binding international law, 108 states had signed, of which 38 were States Parties legally bound by its provisions. Over the past five years another 46 signatories have ratified and nine countries have acceded, bringing the number of countries that are part of the convention to 93 States Parties and 24 signatories.

Slovakia, a former producer and exporter of cluster munitions, acceded to the convention on 24 July 2015 after adopting an action plan that paved the way for its accession. In the past year, Belize, Guyana, and Palestine also acceded to the convention, while five signatories ratified it.

To date, 23 States Parties have destroyed their stocks of cluster munitions, all well in advance of the convention’s eight-year deadline. Collectively States Parties have destroyed more than 1.3 million stockpiled cluster munitions containing 160 million submunitions, representing the destruction of 88% of all cluster munitions and 90% of all submunitions declared stockpiled under the convention.

In 2014 alone, eight States Parties destroyed more than 121,000 cluster munitions and 16.4 million submunitions. Japan completed its stockpile destruction in February 2015, while Canada completed in 2014 before ratifying the convention in March 2015. Another 14 States Parties are in the process of destroying their stocks, of which Botswana, Germany, Italy, Mozambique, and Sweden are working to complete the task in 2015.

A total of 23 States Parties and one signatory have enacted specific legislation to enforce the convention’s provisions, while 28 others have indicated that existing laws will suffice to ensure their adherence. Some 80% of States Parties have provided initial transparency reports detailing the actions they have taken to implement and promote the convention.

There have been no reports or allegations of any States Parties engaging in activities banned by the Convention on Cluster Munitions since before 2008, when the convention was adopted in Dublin on 30 May and opened for signature in December.[2]

However, new use of cluster munitions in states outside the convention in 2015 is providing the greatest challenge for those working to end to suffering caused by the weapons. Cluster munitions have been used in seven states since August 2010, including in the first half of 2015 in Libya, Sudan, Syria, Ukraine, and Yemen.

This use of a banned weapon and the resulting civilian casualties has been met with swift public outcry and widespread media coverage. It has been condemned by more than 140 states, including resolutions by the European Parliament, UN General Assembly, and UN Security Council. These responses contribute to the stigma the convention is establishing against any use of cluster munitions. They also show how many non-signatories are disturbed by the use of cluster munitions even if they themselves have not yet relinquished the weapons.

Recent users of cluster munitions have denied using them or argued the weapon used was not a cluster munition, providing another indicator of the stigma attached to these weapons. Yet they have ignored multiple calls from States Parties and the CMC to accede to the Convention on Cluster Munitions.

Other past users of cluster munitions, such as Israel, Russia, and the United States (US), as well as states where the weapons have been used, such as Cambodia, Ethiopia, Serbia, Sudan, Tajikistan, and Vietnam, also have yet to heed calls to accede to the convention.

Several non-signatories such as Estonia, Greece, Latvia, and Romania committed to reassess their position on accession to the ban convention once Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW) deliberations on regulating cluster munitions concluded. Yet none of these states have reassessed their stance on the ban since the CCW’s Fourth Review Conference failed to conclude a new protocol on cluster munitions in 2011, effectively ending its deliberations on cluster munitions.[3]

The Convention on Cluster Munitions and its sister instrument, the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty, represent the best examples of the alternative humanitarian disarmament path, which places humanitarian considerations and the protection of civilians ahead of narrow, perceived national security interests.[4] Another hallmark of humanitarian disarmament is seen in the collaboration of the close-knit community of states, UN agencies, ICRC, and CMC that works to promote universalization of the convention and ensure that its norms are respected and implemented by all.

The advances made by this global movement under the Convention on Cluster Munitions over the past five years are impressive, but must continue after the convention’s First Review Conference in September 2015. New use and continued stockpiling by states outside the convention, as well as new victims from cluster munition remnants, underscore the need for all to redouble their efforts to encourage universalization and implementation of the convention in the coming period leading up to its Second Review Conference in 2020.

This ban overview covers activities during the second half of 2014 and the first half of 2015, and sometimes later when data was available. Where possible it provides five-year overviews of progress made since the convention’s 2010 entry into force. All findings are drawn from detailed country profiles available on the Monitor website.[5]

“Universalization” refers to the process of non-signatory countries joining the Convention on Cluster Munitions, usually through accession. It also refers to the ratifications required by countries that signed the convention prior to its entry into force on 1 August 2010. Both processes often involve some form of parliamentary approval, typically in the form of legislation.

Since the convention took effect in 2010, states can no longer sign, but instead join through a process known as accession, which is essentially a process that combines signature and ratification into a single step.[6] Mauritius appears to be closest to completing its accession to the convention.

Almost all of the convention’s 24 signatories have committed to ratify and most are in the process of either consulting on ratification or engaging in parliamentary approval of ratification, as the following regional summaries show.[7] Colombia, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Iceland, Madagascar, Rwanda, and Somalia appear to be the closest to completing their ratification of the convention.

Five-Year Review

Since the Convention on Cluster Munitions became binding international law in 2010, the number of countries that are part of the convention has risen from 108 to 117, following accessions by nine countries.[8] Belize, Guyana, Palestine, and Slovakia have acceded since the publication of Cluster Munition Monitor 2014 in September 2014.[9]

A total of 46 signatories have ratified the convention since August 2010 to become States Parties, including Canada, Republic of the Congo, Guinea, Paraguay, and South Africa since Cluster Munition Monitor 2014 was published.[10]

Regional universalization developments

Africa

Of the 49 states in sub-Saharan Africa, 24 have ratified the convention and Swaziland has acceded, making a total of 25 States Parties from the region.

Former cluster munition producer South Africa ratified on 28 May 2015, while Guinea, which is believed to have a stockpile of cluster munitions, ratified on 21 October 2014. The Republic of the Congo ratified on 2 September 2014 during the convention’s Fifth Meeting of States Parties, hosted by Costa Rica in San José.

Five African signatories have either completed or are undertaking parliamentary or executive approval processes to ratify the convention. Rwanda’s parliament adopted legislation approving ratification of the convention in 2011 and Rwanda’s president signed an executive order approving ratification in December 2014. Madagascar’s parliament enacted legislation approving its ratification of the convention on 12 May 2015 and the last remaining step is for it to deposit the ratification instrument. The DRC’s parliament adopted ratification legislation for the convention in November 2013 that was undergoing a judicial review in June 2015. Somalia’s Prime Minister Omar A. A. Sharmarke signed the country’s instrument of ratification for the convention on 31 July 2015 and gave it to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to deposit. Liberia’s government introduced draft legislation to ratify the convention in parliament on 22 July 2015.[11]

The other 11 signatories to the convention from sub-Saharan Africa have all expressed their intent to ratify, and some have undertaken consultations on the matter, but none are known to have introduced ratification measures for parliamentary consideration and approval.[12]

Most of the eight non-signatories from Sub-Saharan Africa have shown interest in the convention over the past five years, but only Mauritius appears to have taken any steps towards accession.[13]The Council of Ministers of Mauritius (the government’s executive body) approved accession to the convention on 26 June 2015.[14]

A Gabonese official attended a regional workshop on universalization of the convention in April 2015, indicating an interest in the convention, but Gabon has not provided a timeframe for accession.[15] Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Zimbabwe have participated in a number of meetings of the convention and expressed interest in joining, but have not taken any steps towards accession.

Sudan has steadfastly ignored calls to accede to the convention, which intensified after new cluster munition use was recorded in early 2015. In September 2014, South Sudan acknowledged that an “unfortunate incident” of cluster munition occurred earlier in the year near the town of Bor and pledged not to use cluster munitions, but did not indicate when it might accede to the convention.[16] Equatorial Guinea has never expressed its view on accession to the convention and last spoke on cluster munitions in 2007.

Americas

Of the 35 states from the Americas, 22 are States Parties to the convention, while three signatories still need to ratify.[17]

Belize acceded to the convention on 2 September 2014 during the convention’s Fifth Meeting of States Parties. This was the first accession to the convention since Saint Kitts and Nevis a year before in September 2013. Guyana followed with its accession on 31 October 2014. Paraguay ratified the convention on 12 March 2015, while Canada ratifed four days later on 16 March 2015, after adopting legislation to implement and ratify the convention in late 2014.

Colombia enacted legislation approving its ratification of the convention in December 2012, but stated in May 2015 that it is conducting stakeholder consultations.[18] During a 10 August 2015 meeting with CMC representatives, Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos committed to ensure that Colombia completes its ratification by the First Review Conference.[19] In September 2014, Jamaica stated it is preparing “applicable domestic legislation” with the goal of ratifying the convention “at its earliest opportunity.”[20] The status of Haiti’s ratification process is not known.

The 12 non-signatories from the Americas region include states with long-held objections to the convention—namely Argentina, Brazil, Cuba, the US, and Venezuela—as well as smaller states with less capacity to undertake the accession process: Bahamas, Barbados, Dominica, Saint Lucia, and Suriname. Argentina and Cuba were the only non-signatories from the region to participate in the convention’s Fifth Meeting of States Parties in September 2014.

Asia-Pacific

Just 12 of the 40 states from the Asia-Pacific region have signed the Convention on Cluster Munitions, of which nine are States Parties.[21] There have been no accessions from Asia-Pacific, while the region’s last ratification was the Pacific island state of Nauru in February 2013.[22]

Asia-Pacific signatories Indonesia, Palau, and the Philippines all state that they are pursuing ratification, but none are known to have introduced ratification legislation into their respective parliaments for consideration and approval. Indonesia and the Philippines still do not appear to have concluded their years-long stakeholder consultations on ratification of the convention.

Non-signatories China, Mongolia, and Thailand participated as observers in the convention’s the Fifth Meeting of States Parties in September 2014, while Cambodia and Vietnam were absent, unlike in previous years.

More than a dozen non-signatories from the Asia-Pacific region still have not made a public statement articulating their position on joining the convention.[23]

Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia

Of the 54 countries in Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia, 31 have signed and ratified the convention and two have acceded to make a total of 33 States Parties.[24]

Former producer and exporter Slovakia acceded to the convention on 24 July 2015, after adopting an action plan for accession in January 2014. With this accession, all but seven of the European Union’s (EU) 28 member states are now party to the convention.[25]

In Finland, a cabinet committee has conducted annual reviews of the convention and accession since 2009, but has yet to recommend the government amend its stance toward joining.[26] Latvia regularly informs the Monitor of its “firm support” for the convention’s objectives and states that it “de-facto complies” with the convention’s provisions, but has not taken any steps to accede.[27] Poland also communicates regularly with the Monitor, stating in April 2015 that despite its lack of accession it “takes precautions to limit the inhumane effects of [cluster] munitions.”[28]

Estonia, Greece, Latvia, and Romania committed to reevaluate their stance on joining the convention after the CCW concluded its work on cluster munitions. Yet none of these states have done so since the CCW ended its deliberations on cluster munitions in 2011. Nor have they made any concrete proposals for the CCW to address cluster munitions again.

Serbia’s Minister of Defense said in April 2015 that the government would consider accession to the convention after new weapons are acquired to replace the country’s stocks of cluster munitions.[29]

Russia and the eight states from the Caucasus and Central Asia that remain outside the Convention on Cluster Munitions have made even less progress toward joining.[30] Both Ukraine and Russia have ignored calls to accede to the convention since cluster munition rocket attacks were first documented in eastern Ukraine in mid-2014.

Tajikistan has participated in all of the convention’s Meetings of States Parties and states that it is studying the convention, but progress towards accession has stalled since 2011. Armenia informed States Parties in September 2014 of its hope to join the convention, but stated it cannot accede at this time due to the regional security situation.[31]

Iceland adopted ratification and implementation legislation for the convention on 30 June 2015, which was signed into law on 10 July 2015. The last remaining step is for it to deposit the ratification instrument. The parliament of Cyprus has been considering draft ratification legislation for the convention since 2011, where the convention is viewed positively, but there are concerns over Turkey’s absence from the convention.[32]

Middle East and North Africa

The four States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions from the Middle East and North Africa are Iraq, Lebanon, Palestine, and Tunisia.[33]

The State of Palestine acceded to the convention on 2 January 2015 after making several positive statements indicating its intent to join.

None of the 15 non-signatories from the Middle East and North Africa have indicated they are considering accession to the convention.[34] Saudi Arabia and the other states from the region that have been participating in a coalition operation against Ansar Allah forces (also known as the Houthis) in Yemen since March 2015 have ignored calls to cease using cluster munitions and join the convention.[35]

Meetings on cluster munitions

Several key meetings related to the Convention on Cluster Munitions took place in the second half 2014 and the first half of 2015, providing opportunities to promote universalization of the convention.[36]

Costa Rica hosted the Fifth Meeting of States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions in San José, Costa Rica from 2–5 September 2014. A total of 98 states (60 States Parties, 16 signatories, and 22 non-signatory observers) attended, in addition to representatives from UN agencies, the ICRC, and the CMC.[37] Costa Rica’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Manuel Gonzalez Sanz, was elected President of the meeting and was represented by Costa Rica’s Permanent Representative to the UN in Geneva, Ambassador Christian Guillermet Fernández. The meeting received significant media attention after Belize acceded to the convention on the opening day, making Central America the first sub-region to have universalized the convention and become a zone free of cluster munitions.

Several regional workshops aimed at encouraging universalization and implementation of the Convention on Cluster Munitions took place in the first half of 2015. Norway and Ecuador convened an informal workshop on the convention for Southeast Asia states in Geneva on 24 March 2015.[38] Costa Rica and Croatia together with CMC members Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA) and PAX held a workshop on the convention for states from sub-Saharan Africa in New York on 16 April 2015.[39] A workshop on cluster munitions was held during the seventh annual mine action symposium by the Regional Arms Control Verification and Implementation Assistance Centre (RACVIAC) at the Centre for Security Cooperation in Biograd, Croatia on 27–30 April 2015.[40] Norway, with the support of CMC members Uganda Landmine Survivors Association and NPA, convened a workshop on the convention for East African Community member states in Kampala, Uganda on 19 May 2015.[41] Zambia and the ICRC co-hosted a seminar on the convention for Southern African Development Community (SADC) member states in Lusaka on 17–18 June 2015.[42]

The fifth round of intersessional meetings of the Convention on Cluster Munitions took place in Geneva on 22–23 June 2015, with participation from representatives of 56 countries in addition to UN agencies, the ICRC, and the CMC.[43]

Croatia will host the convention’s First Review Conference in Dubrovnik from 7–11 September 2015.[44]

Global overview

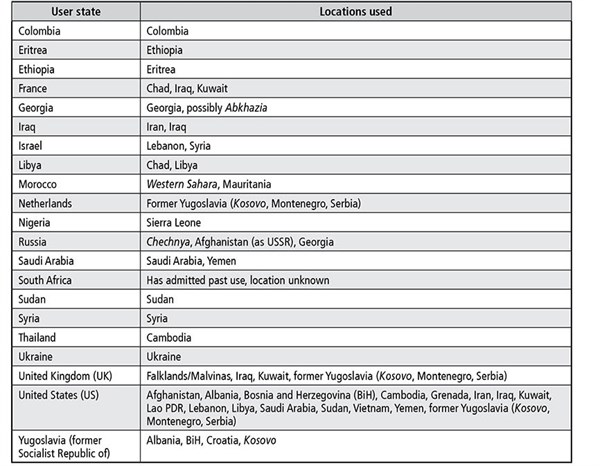

Cluster munitions have been used by at least 23 governments in 39 countries and four disputed territories since the end of World War II (as detailed in the following table and the Timeline of cluster munition use found at the end of this chapter). Almost every part of the world has experienced cluster munition use at some point over the past 70 years, including Southeast Asia, Southeast Europe, the Caucasus, the Middle East and North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America.

Summary of states using cluster munitions and locations used[45]

Note: Other areas are indicated in italics.

The US, Israel, and Syria—all non-signatories to the Convention on Cluster Munitions—have been among the most prolific users of cluster munitions, while the vast majority of states outside the convention have never used them.[46] Only three non-signatories are considered major users and producers of cluster munitions: Israel, Russia, and the US.[47]

Article 1 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions contains the convention’s core preventive measures designed to eliminate future humanitarian problems from cluster munitions, most crucially the absolute ban on the use of cluster munitions. Many countries that used cluster munitions in the past are now either States Parties (France, Iraq, the Netherlands, South Africa, and the UK) or have signed (Colombia and Nigeria) the Convention on Cluster Munitions, and have relinquished use of cluster munitions.

Article 4 of the convention addresses the clearance of cluster munition remnants and is not retroactive, but affirms that a State Party that previously used cluster munitions that became remnants on the territory of another State Party before the convention’s entry into force for both states is “strongly encouraged” to provide assistance to the affected State Party.

Five-year review of cluster munition use

There have been no confirmed reports or allegations of new use of cluster munitions by any State Parties to the convention. However, cluster munitions have been used in seven non-signatories to the convention since its August 2010 entry into force:

- Thailand fired cluster munition rockets into Cambodia during border clashes in February 2011;

- Cluster bombs were dropped on two locations in Libya in early 2015, but it was not possible to conclusively determine responsibility. Previously, in April 2011, Libyan government forces loyal to Muammar Gaddafi fired cluster munition mortar rounds into Misrata city;

- Syrian government forces began using air-dropped cluster bombs in mid-2012 and then cluster munition rockets in attacks that are believed to be continuing, while Islamic State (IS) forces used cluster munition rockets in the second half of 2014;

- Cluster bombs were dropped near the South Sudanese town of Bor in early 2014, but it’s unclear who was responsible for this use;

- Ukrainian government forces and Russian-backed anti-government forces used cluster munition rockets in Donetsk and Luhansk provinces of eastern Ukraine in attacks that started in 2014 and stopped after a February 2015 ceasefire;

- Sudan’s armed forces used air-dropped cluster bombs in Southern Kordofan province in the first half of 2015 and previously in 2012;

- One or more members of a Saudi Arabia-led coalition has used air-dropped cluster munitions in northern Yemen since 25 March 2015 in operations against Ansar Allah forces (the Houthis), while it is currently not clear who used ground-fired cluster munition rockets that have also been recorded.

Since 2010, there was also an allegation that a weapon that appears to meet the criteria of a cluster munition was used in non-signatory Myanmar in early 2013.[48]

In this reporting period—since 1 July 2014—cluster munitions have been used in Libya, Sudan, Ukraine, Syria, and Yemen, as summarized below (for a more detailed accounting, please see the relevant country profile).

Use in Syria

Syrian government forces have used cluster munitions in multiple locations across 10 of the country’s 14 governorates since mid-2012.[49] At least seven types of cluster munitions have been used, including air-dropped bombs, dispensers fixed to aircraft, and ground-launched rockets, and at least eight types of explosive submunitions.[50] IS forces have used at least one type of rocket-fired cluster munition and submunition (the “ZP-39”).

Initial reports of the use of RBK-series air-dropped cluster bombs containing AO-1SCh and PTAB-2.5M bomblets emerged in mid-2012, when the government began its air campaign on rebel-held areas.[51] It continued to use cluster bombs in 2013 and 2014, including RBK-500 cluster bombs containing ShOAB-0.5 submunitions and AO-2.5RT and PTAB-2.5KO submunitions.[52] There is some evidence of Syrian government use of air-dropped cluster bombs in 2015, but significantly less than previous years as government forces have intensified their use of other air-dropped munitions such as improvised “barrel bombs.”[53]

On 15 August 2014, the local authority of `Ayn al-`Arab or Kobani (in Kurdish) on Syria’s northern border with Turkey issued a warning for locals to avoid cluster munition remnants “fired by Daash [IS] mercenaries on villages” near the city. From photos and video, Human Rights Watch confirmed that IS forces used a Dual Purpose Improved Conventional Munition (DPICM)-like submunition in its advance on Kobani in July and August 2014.[54] Featuring a distinctive red nylon stabilizing ribbon, the country of origin and information about the “ZP-39” submunition is not known, but it may have been delivered by Sakr rocket.[55]

Several videos posted online from Syria, as recently as June 2015, show remnants of Sakr cluster munition rockets and/or unexploded DPICM submunitions including “ZP-39” submunitions, indicating continued use of the cluster munition rockets by government and/or IS forces.

As the conflict in Syria worsens, it is becoming much harder to determine with confidence if cluster munitions have been used by opposition groups other than IS. There is some evidence that opposition forces have utilized unexploded submunitions as improvised explosive devices (IEDs).[56] There is no evidence to indicate that the US is using cluster munitions in the “Operation Inherent Resolve” military action against IS forces that began last year in Syria and Iraq.

Responses to the use of cluster munitions

The Syrian military has denied possessing or using cluster munitions and the government usually does not respond to or comment on its use of cluster munitions.[57] IS has not responded to its reported use of cluster munitions.

The cluster munition use in Syria has attracted widespread media coverage, public outcry, and condemnations by more than 140 states since 2012.[58] At least 41 of these states have made national statements to condemn the use, including the foreign ministers of States Parties Austria, Belgium, Costa Rica, Denmark, France, Germany, Mexico, Norway, and the UK.[59]

Three UN General Assembly (UNGA) resolutions condemning the use of cluster munitions in Syria have been adopted since May 2013.[60] Four Human Rights Council resolutions have been adopted that condemn the use of cluster munitions in Syria, most recently on 2 July 2015.[61]

More than two dozen states condemned the use of cluster munitions in Syria at the Fifth Meeting of States Parties in September 2014, while in a statement to the meeting, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon described “the carnage caused by cluster munitions in Syria” as “a direct violation” of international humanitarian law.[62]

Use in Ukraine

Cluster Munition Monitor 2014 reported evidence that emerged in July 2014 strongly indicating the use of ground-launched cluster munition rockets in Donetsk province in eastern Ukraine as fighting began between Ukrainian government forces and armed opposition supported by Russia.[63] Field research conducted by Human Rights Watch in October 2014 and a follow-up investigation in January–February 2015 confirmed the use of cluster munitions by both Ukrainian government forces and Russian-backed anti-government forces in dozens of urban and rural locations of Donetsk and Luhansk provinces.[64] An Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) monitoring mission has also reported on the cluster munition rocket attacks since late 2014.

Both parties to the conflict have used two types of cluster munitions fired from dedicated launch tubes mounted on vehicles:

- The 300mm 9M55K-series Smerch (“Tornado”) cluster munition rocket, which has a minimum range of 20 kilometers and a maximum range of 70 kilometers, and delivers 72 9N235 submunitions.

- The 220mm 9M27K-series Uragan (“Hurricane”) cluster munition rocket, which has a range of 10–35 kilometers and delivers 30 9N235 submunitions or 30 9N210 submunitions.

The 9N210 and 9N235 are fragmentation submunitions designed to self-destruct a minute or two after being ejected from the rocket.[65] These rockets and submunitions appear to fall under the category of “inaccurate and unreliable” cluster munitions that Ukraine has expressed concern about in the past, as their remnants pose a long-term threat until cleared and destroyed.[66]

As of 1 August 2015, no cluster munition rocket attacks have been recorded in eastern Ukraine since the ceasefire went into effect on 16 February 2015. There has been no evidence to indicate that cluster munitions have been used elsewhere in Ukraine, for example, in Crimea.

Neither party to the conflict has taken responsibility for use of cluster munitions in eastern Ukraine. Ukraine has repeatedly denied the use of cluster munitions by its armed forces since October 2014, when it blamed the use on pro-Russian separatist groups.[67] Russia has repeatedly drawn attention to Ukraine’s use of cluster munitions, but has not itself acknowledged or taken any responsibility for cluster munition rocket attacks by the armed opposition fighters supported by Russia.[68]

The cluster munition rocket attacks in Ukraine have attracted widespread media coverage, public outcry, and condemnations by at least 32 states and the European Union.[69] At the convention’s Fifth Meeting of States Parties in September 2014, 21 states expressed concern at/or condemned the reported use of cluster munitions in Ukraine.[70] During a UN Security Council debate on Ukraine on 24 October 2014, 11 of the Council’s 15 member states expressed specific concern at the reported use of cluster munitions in Ukraine with most calling for an investigation.[71] At an OSCE meeting on 29 October 2014, the US and the European Union expressed concern at reports of cluster munition use and requested an investigation, while Ukraine denied the use, but agreed to investigate.[72]

Ukraine has stated several times that it is willing to conduct its own investigation and cooperate with other investigations into the cluster munition use.[73] In October 2014, Ukraine’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Pavlo Klimkin, denied the cluster munition use, but said the “serious accusations…deserve the deepest investigation.”[74] However, in December 2014, high-level Ukraine government officials informed Human Rights Watch representatives that an internal review of stocks had found no evidence of cluster munition use by Ukrainian armed forces.[75]

Use in Libya

In February and March 2015, remnants of air-dropped cluster bombs were recorded at Bin Jawad and Sirte respectively. The Libyan Air Force admitted to bombing both locations in early 2015 during attacks against Libya Dawn forces, but denied using cluster munitions.[76]

Human Rights Watch identifed the munitions used as air-dropped RBK-250 PTAB 2.5M cluster bombs, but found it was not possible to conclusively determine responsibility for the use on the basis of available evidence.[77]

At the convention’s intersessional meetings in June 2015, seven states expressed concern at and/or condemned the new use of cluster munitions in Libya in addition to the UN, the ICRC, and the CMC.[78] In March 2015, Sweden’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs described evidence of new use of cluster munitions in Libya as a “worrisome development” and called on Libya to accede to the ban convention.[79]

Use in Sudan

Sudan used air-dropped cluster bombs in Southern Kordofan state several times in the first half of 2015, most recently on 27 May 2015. Cluster munition use was previously recorded in 2012 in the state, which borders South Sudan and has experienced fighting between the Sudan Armed Forces and the Sudan People’s Liberation Army North (SPLM-N) since mid-2011, when South Sudan became independent.

In May 2015, Human Rights Watch reported that government aircraft dropped two cluster bombs on Tongoli village in Delami county on 6 March 2015 and four bombs on Rajeefi village in Um Durein county in late February 2015.[80] Human Rights Watch identified the weapons used as RBK-500 cluster bombs containing AO-2.5 RT submunitions. In June 2015, Nuba Reports—a network of local journalists in the Nuba Mountains where Southern Kordofan is located—published video showing the remnants of RBK-500 cluster bombs containing AO-2.5 RT submunitions that it said was filmed in Kauda, a town in the region, after a government air attack on 27 May 2015. In almost all of these documented incidents the cluster munitions failed to function as designed, leaving failed munitions and unexploded submunitions. Two days after the Kauda attack, SPLM-N soldiers removed and “rolled the bomblets into a hole, covered them with dirt, and marked them with thorn bushes.”[81]

Sudan has repeatedly denied using cluster munitions.[82] In various media comments, Sudanese Army spokesperson, Col. Alswarmy Khalid, denied responsibility for the use detailed in the May 2015 Human Rights Watch report.[83] Sudan’s Geneva-based representatives denied the cluster munition use in a May 2015 meeting with CMC representatives.[84]

The cluster munition attacks in Sudan in the first half of 2015 have been met with strong media coverage, public outcry, and condemnations by at least 23 states.[85] On 29 June 2015, the UN Security Council unanimously adopted a UK-led resolution that—for the first time on Sudan—contained specific language on cluster munitions “expressing concern at evidence, collected by AU-UN Hybrid Operation in Darfur (UNAMID), of two air-delivered cluster bombs near Kirigiyati, North Darfur, taking note that UNAMID disposed of them safely, and reiterating the Secretary-General’s call on the Government of Sudan to immediately investigate the use of cluster munitions.”[86] Sudan’s representative at the UN Security Council session objected “strenuously” to the paragraph.[87]

Use in Yemen

Saudi Arabia is leading a coalition of states that began attacking Ansar Allah forces (the Houthis) in Yemen on 25 March 2015, in a conflict that is continuing as of 1 August 2015.[88] The coalition has used two types of air-dropped cluster munitions in Yemen’s northern Saada governorate, while a cluster munition rocket has also been used, but it is not clear who was responsible.

Human Rights Watch has documented at least two instances of use of US-made and supplied CBU-105 Sensor Fuzed Weapons, which deploy 10 BLU-108 canisters that each subsequently release four submunitions called “skeets” by the manufacturer: at al-Shaaf in Saqeen in the western part of Sadaa governorate on 17 April and near al-Amar area in al-Safraa, 30 kilometers south of Saada City on 27 April.[89] A subsequent Human Rights Watch research visit to al-Amar confirmed the cluster munition use, reviewing physical evidence of the remnants of BLU-108 canisters.

A Saudi military spokesman acknowledged use of the CBU-105 (see below), although the United Arab Emirates also possesses them and could be responsible.

The Saudi coalition also used US-made BLU-97 submunitions, 202 of which are contained in each CBU-87 bomb, in the al-Maqash and al-Nushoor districts of Saada City on 23 May 2015.

Ground-launched cluster munitions containing “ZP-39” submunitions were found near Baqim in Saada province on 29 April 2015, but it was not possible to determine who was responsible.[90] Neither Saudi Arabia nor Houthi forces are known to possess this type of weapon, but both sides have rocket launchers and tube artillery capable of delivering them.[91]

Evidence of the use of a fourth type of cluster munition emerged on social media in June and July 2015, but had not been confirmed as Cluster Munition Monitor 2015 went to print.[92]

As of 1 August 2015, the government of Saudi Arabia has not issued a formal statement to confirm or deny the Saudi-led coalition’s use of cluster munitions in Yemen.[93] In numerous media interviews, Saudi Arabia’s military spokesperson Brig. Gen. Ahmed Asiri acknowledged use of CBU-105 cluster munitions in Yemen, but argued they have not been used in civilian areas or against civilians, and are not prohibited weapons.[94] Saudi Arabia has not commented on the BLU-97 submunitions used by Saudi-led coalition forces.

CBU-105 Sensor Fuzed Weapons are banned by the Convention on Cluster Munitions as they fall under the convention’s definition of a cluster munition specified in Article 2. The US government acknowledges that the CBU-105 version of the Sensor Fuzed Weapon is the only cluster munition in the active US inventory “that meet[s] our stringent requirements for unexploded ordnance rates, which may not exceed 1 percent.”[95] Human Rights Watch found evidence that CBU-105 Sensor Fuzed Weapons fell within 600 meters of villages in one attack, in possible violation of US law. It also found that some of the cluster munitions malfunctioned as their submunitions failed to disperse from the canister or dispersed but did not explode.[96]

Saudi Arabia and other members of the coalition possess attack aircraft of US and Western/NATO origin capable of dropping US-made cluster bombs, while Yemen’s Soviet supplied aircraft are not capable of delivering US-made cluster bombs. Houthi forces are not known to operate aircraft capable of using cluster munitions, but may have access to ground-fired cluster munitions.

The use of cluster munitions in Yemen has received worldwide media coverage, public outcry, and condemnations by a dozen states, including Costa Rica as president of the convention’s Fifth Meeting of States Parties.[97] On 9 July 2015, the European Parliament adopted a resolution condemning the Saudi-led coalition airstrikes in Yemen, including the use of cluster bombs.[98] During a European Parliament debate on 13 July 2015, European Parliament member Marietje Schaake requested that reports of cluster munition use by the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen “be investigated thoroughly by the United Nations” as they “have serious consequences.”[99]

Unilateral restrictions on use

Several states that have not joined the Convention on Cluster Munitions have imposed restrictions on the possible future use of cluster munitions.

The US confirmed in November 2011 that its policy on cluster munitions is still guided by a June 2008 US Department of Defense directive requiring that any US use of cluster munitions before 2018 that results in a 1% or higher unexploded ordnance (UXO) rate—which includes all but a tiny fraction of the US arsenal—must be approved by a “Combatant Commander,” a very high-ranking military official. After 2018, the US will no longer use cluster munitions that result in more than 1% UXO.

Romania has stated it restricts the use of cluster munitions to exclusively on its own territory. Poland has stated it would use cluster munitions for defensive purposes only, and does not intend to use them outside its own territory. Estonia and Finland have made similar declarations.

In December 2013, a Greek defense blog reported on “intense debate” by the General Staff of the Greek Armed Forces over procurement efforts to modernize the country’s stocks of ammunition for the M270 Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS) due to the apparent requirement that it “select and implement a solution within a global binding environment that is required by international treaty to ban cluster munitions.”[100]

During the failed CCW negotiations on cluster munitions, several states that have not signed or ratified the Convention on Cluster Munitions publicly stated that they were prepared to accept a ban on the use of cluster munitions produced before 1980 as part of the proposed CCW protocol, including China, India, South Korea, and Russia. The CMC has called on these states to institute the commitments they made at the CCW as national policy as an interim measure towards joining the Convention on Cluster Munitions.

Non-State Armed Groups

Due to the relative sophistication of cluster munitions and their delivery systems, very few non-state armed groups (NSAGs) have used them.

In the past, NSAG use of cluster munitions has been recorded in Afghanistan (by the Northern Alliance), BiH (by a Serb militia), Croatia (by a Serb militia), and Israel (by Hezbollah). For the first time since 2006, cluster munitions were used by NSAGs in two countries in the second half of 2014: by IS in Syria and by Russian-backed opposition forces in Ukraine.[101]

Government forces used cluster munitions against NSAGs in Libya, Sudan, Syria, Ukraine, and Yemen in 2014 and/or early 2015, while in the past, cluster munitions were used against NSAGs in several countries, including Lebanon, Libya, South Sudan, and Syria, as well as in Abkhazia, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Western Sahara.[102]

Production of Cluster Munitions

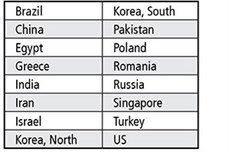

A total of 34 states have developed or produced[103] more than 200 types of cluster munitions.[104] Half of these producers ceased manufacturing cluster munitions prior to or as a result of joining the Convention on Cluster Munitions.

Producers

Sixteen countries are believed to produce cluster munitions or reserve the right to do so.[105] None of these states have joined the Convention on Cluster Munitions. Asia and Europe account for the majority of producer states, with six and five producers respectively, while the Middle East and North Africa has three producer states and two producers are from the Americas.

Cluster munition producers

It is not known if cluster munitions were produced in all these countries in 2014 or the first half of 2015 due to lack of transparency and available data.

In early 2015, state-owned company Israel Military Industries (IMI) was put up for sale as part of a privatization measure and the government apparently intends to sell it to the highest qualified bidder by the end of the year.[106] IMI has produced, license-produced, and exported cluster munitions.[107]

Previously, Greece informed the Monitor that its last production of cluster munitions was in 2001.[108] India stated that it did not produce any cluster munitions in 2011.[109]

At least three cluster munition producers have established specific standards aimed at addressing the weapon’s failure rate and resulting unexploded ordnance (UXO):

- Poland stated in 2005, “The Ministry of Defense requires during acceptance tests less than 2.5% failure rate for the purchased submunitions.”[110]

- South Korea in 2008 issued a directive requiring that in the future it would only acquire cluster munitions with self-destruct mechanisms and a 1% or lower failure rate.[111]

- The US in 2001 instituted a policy that all submunitions reaching a production decision in fiscal year 2005 and beyond must have a UXO rate of less than 1%.[112]

Former producers

Under Article 1(b) of the Convention on Cluster Munitions, States Parties undertake to never develop or produce cluster munitions. Since the convention entered into force on 1 August 2010, there have been no confirmed instances of new production of cluster munitions by any of the convention’s States Parties or signatories.

Eighteen states have ceased the production of cluster munitions, as shown by the following table. All are States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions except non-signatory Argentina, which has indicated that it does not intend to produce cluster munitions in future.

Former producers of cluster munitions

Several States Parties have provided information on the conversion or decommissioning of production facilities in their Article 7 transparency reports, including France, Japan, Sweden, and Switzerland.[113]

The true scope of the global trade in cluster munitions is difficult to ascertain due to the overall lack of transparency on arms transfers. Despite this challenge, the Monitor has identified at least 15 countries that have in the past transferred more than 50 types of cluster munitions to at least 60 other countries.[114]

Exporters and recent transfers

Since joining the Convention on Cluster Munitions, no State Party is known to have transferred cluster munitions other than for the purposes of stockpile destruction or for research and training purposes. States Parties Chile, France, Germany, Moldova, Slovakia, Spain, and the UK exported cluster munitions before they adopted the Convention on Cluster Munitions in May 2008.

While the historical record is incomplete and there are large variations in publicly available information, the US has probably been the world leader in exports, having transferred hundreds of thousands of cluster munitions containing tens of millions of submunitions to at least 30 countries and other areas.[115] Cluster munitions of Russian/Soviet origin are reported to be in the stockpiles of at least 36 states, including countries that inherited stocks after the dissolution of the USSR.[116] The full extent of China’s exports of cluster munitions is not known, but unexploded submunitions of Chinese origin have been found in Iraq, Israel, Lebanon, and Sudan.

Non-signatories Brazil, Israel, South Korea, Turkey, Ukraine, and the US are known to have exported cluster munitions since 2000. The use of US-manufactured and supplied CBU-105 cluster munitions by a Saudi Arabia-led coalition in Yemen in 2015 is raising questions about whether US transfer requirements are being met.[117]

Non-signatories Georgia, India, Pakistan, Slovakia, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) are among the recipients of cluster munitions exports since 2005.

At least two states that have not joined the Convention on Cluster Munitions have enacted an export moratorium: Singapore and the US.[118] In a March 2015 response to a Monitor request for information, South Korea declared it would not release information on its exports of cluster munitions and stated, “the ROK has not established moratorium policy” on future exports. [119]

Stockpiles of Cluster Munitions and their Destruction

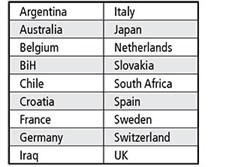

Global stockpiles

The Monitor estimates that prior to the start of the global effort to ban cluster munitions, 91 countries stockpiled millions of cluster munitions containing more than one billion submunitions, as shown in the following table.[120] At least 26 of these states have destroyed their stockpiled cluster munitions, while 15 States Parties to the convention are in the process of destroying their stocks.

Countries that have stockpiled cluster munitions

Note: Countries in italics report no longer possessing stockpiles.

Stockpiles possessed by non-signatories

It is not possible to provide a global estimate of the quantity of cluster munitions currently stockpiled by non-signatories to the Convention on Cluster Munitions as so few have disclosed information on the types and quantities possessed.[121]

The US stated in 2011 that its stockpile comprised of “more than 6 million cluster munitions.”[122] However, it appears to have made significant progress since 2008 in removing the cluster munitions from the active inventory and destroying them through demilitarization, despite a lack of detailed information on the process, including the number and types destroyed. In February 2015, the Army disclosed that there are currently “approximately 221,502 tons of cluster munitions in the demil[itarization] stockpile” and “an additional 250,224 tons are expected to be added into the [demilitarization account] no later than FY [fiscal year] 2018 to ensure compliance with the Cluster Munitions Policy.”[123]

Georgia completed the destruction of a significant stockpile of 844 RBK-series cluster bombs containing 320,375 submunitions in 2013, but it is unclear if it holds additional stocks of cluster munitions.[124] Greece and the Ukraine have disclosed partial figures on their respective stockpiles of cluster munitions.[125]

Stockpiles possessed by States Parties

A total of 38 States Parties have stockpiled cluster munitions at some point in time, of which 23 have completely destroyed their stockpiles.

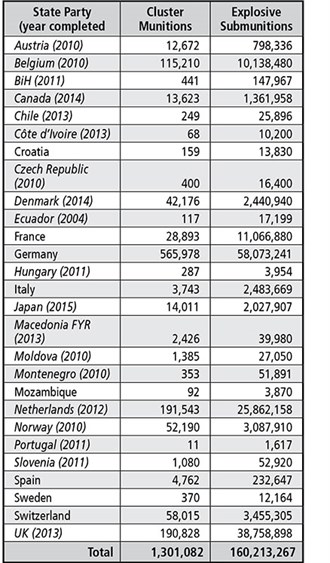

According to available information, at one point 30 States Parties stockpiled nearly 1.5 million cluster munitions containing more than 178 million submunitions, as shown in the following table.

Cluster munitions and explosive submunitions declared by States Parties[126]

Note:Italics indicate states that no longer possess stockpiles.

Another four States Parties are not listed in the table above and currently stockpile cluster munitions that must be formally declared in their initial Article 7 transparency reports:

- Guinea-Bissau acknowledges that it stockpiles cluster munitions, but is nearly four years late in delivering its initial transparency report for the convention.[127]

- Guinea’s stockpile status and plans for its destruction are not known, but its initial transparency report is due by September 2015.

- Slovakia disclosed information on a stockpile of 899 cluster munitions in its January 2014 action accession plan for the convention.[128]

- South Africa has stated that its relatively small stockpile of cluster munitions has been earmarked for destruction.

Stockpiles possessed by signatories

Two signatories have completed stockpile destruction and state that they no longer possess cluster munitions:

- Colombia destroyed a stockpile of 72 cluster munitions and 10,832 submunitions in 2009.[129]

- The Central African Republic stated in 2011 that it had destroyed a “considerable” stockpile of cluster munitions and no longer had stocks on its territory.[130]

Three other signatories acknowledge stockpiling cluster munitions, but have yet to disclose information on the quantities and types or destruction plan:

- Angola stated in 2010 that its entire stockpile had been destroyed and its armed forces no longer possessed cluster munitions.[131] It has yet to make an official declaration that all stocks of cluster munitions were destroyed.

- Indonesia has acknowledged stockpiling cluster munitions, but has not disclosed information on the types and quantities possessed.

- A Nigerian official confirmed in April 2012 that Nigeria has a stockpile of BL-755 cluster bombs.[132]

No stockpiles

A total of 37 States Parties have confirmed never stockpiling cluster munitions, most through a direct statement in their transparency report for the convention.[133] Since September 2014, El Salvador and Trinidad and Tobago have turned in initial transparency reports confirming they do not possess any stocks.

Stockpile destruction

Under Article 3 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions, each State Party is required to declare and destroy all stockpiled cluster munitions under its jurisdiction or control as soon as possible, but no later than eight years after entry into force for that State Party.

States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions have destroyed a total of 1.3 million cluster munitions containing more than 160 million submunitions, as shown in the following table.[134] This represents the destruction of 88% of the total stockpiles of cluster munitions and 90% of the total number of submunitions declared by States Parties.

Cluster munitions destroyed by States Parties

Note: Italics indicate States Parties that have completed stockpile destruction

Prior to the convention’s entry into force for States Parties, a total of 712,977 cluster munitions containing more than 78 million submunitions were destroyed by Belgium, Germany, Netherlands, Switzerland, and the UK.[135]

Five-year review of stockpile destruction under the convention

States Parties have destroyed a total of 532,938 cluster munitions and 85 million submunitions since the convention took effect in 2010:

- In 2011, 10 States Parties destroyed 107,000 cluster munitions and 17.6 million submunitions. BiH, Hungary, Portugal, and Slovenia completed destruction of their stockpiles;

- In 2012, nine States Parties destroyed 173,973 cluster munitions and 27 million submunitions. The Netherlands completed destruction;

- In 2013, 10 States Parties destroyed 130,380 cluster munitions and 24 million submunitions. Chile, Côte d’Ivoire, Macedonia FYR, and the UK completed destruction;

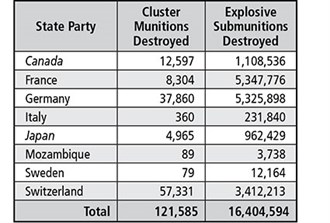

- In 2014, eight States Parties destroyed 121,585 cluster munitions and 16.4 million submunitions. Canada and Denmark completed destruction.

Destruction completed

Seven States Parties completed their stockpile destruction before the convention’s entry into force on 1 August 2010, while 12 States Parties have completed destruction in the period since.

Japan announced the completion of its stockpile destruction on 9 February 2015, more than three years in advance of its August 2018 deadline. Canada destroyed its stockpile of 13,623 cluster munitions and 1.36 million submunitions in 2014, prior to ratifying the convention in March 2015.

Four States Parties that once stockpiled are not listed in the table above due to lack of available information on the total number of cluster munitions destroyed. The Republic of the Congo informed States Parties in 2011 that it had no stocks of cluster munitions; its transparency report is due on 28 August 2015.[136] Honduras stated in 2007 that it no longer possessed a stockpile of cluster munitions, but has yet to deliver its initial transparency report, originally due in February 2013. There has been a lack of clarity in Afghanistan and Iraq’s transparency reports with respect to their reporting of destroyed stocks of cluster munitions.[137]

Destruction underway

In 2014, eight States Parties destroyed 121,585 cluster munitions and 16.4 million submunitions, as shown in the following table.

Cluster munitions destroyed by States Parties in 2014

Note:Italics indicate States Parties that have completed stockpile destruction.

Guinea is the only State Party that has not articulated a stockpile destruction plan. Fourteen States Parties are preparing to begin, or are in the process of, stockpile destruction: Botswana, Bulgaria, Croatia, France, Germany, Guinea-Bissau, Italy, Mozambique, Peru, Slovakia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland.

Five States Parties are working to complete their stockpile destruction this year. Germany had destroyed 99% of its original stockpile of cluster munitions and 92% of its submunitions by the end of 2014 and was on track to complete destruction in 2015.[138] Italy stated in September 2014 that its stockpile destruction process was “on track for completion by 2015.”[139] Mozambique stated in May 2015 that it is working to complete its stockpile destruction by the end of 2015.[140] Sweden informed the Monitor in May 2015 that the stockpile should be completely destroyed by the end of 2015 at the latest.[141] In April 2014, Botswana reported that it plans to destroy its stockpile by the end of 2015.[142]

France reported in April 2015 that “all cluster munitions will be destroyed before 1 August 2018.”[143] Croatia reported in 2014 that it has the necessary capabilities and facilities in place to destroy its stockpile ahead of its August 2018 deadline.[144] Spain enacted implementing legislation for the convention in July 2015 that specifies its obligation to destroy its remaining cluster munition stocks by its August 2018 treaty deadline.[145] Switzerland confirmed in April 2015 that it plans to complete destruction in 2018.[146]

Guinea-Bissau stated in September 2014 that it will require financial and technical assistance to destroy its stockpile by its May 2019 deadline.[147] In 2014, Bulgaria affirmed its determination to meet its October 2019 deadline.[148] In October 2014, Peru confirmed it is preparing to destroy its stockpile by the March 2021 deadline.[149] In April 2015, Slovakia affirmed its commitment to destroy the stockpile “within the given timeframe.”[150] Slovakia's stockpile destruction deadline is 1 January 2024.

Destruction costs

More than US$112 million has been spent on cluster munition stockpile destruction by States Parties BiH, Croatia, Denmark, Japan, Moldova, Norway, Spain, Sweden, and the UK.

At least $133 million has been allocated or estimated as necessary for the destruction of stockpiled cluster munitions by States Parties France (€20.2 or $26.9 million), Germany (€41.4 million or $55.0 million), Slovakia (€5.5 million or $7.3 million), and Switzerland (CHF40 million or $43.7 million).[151]

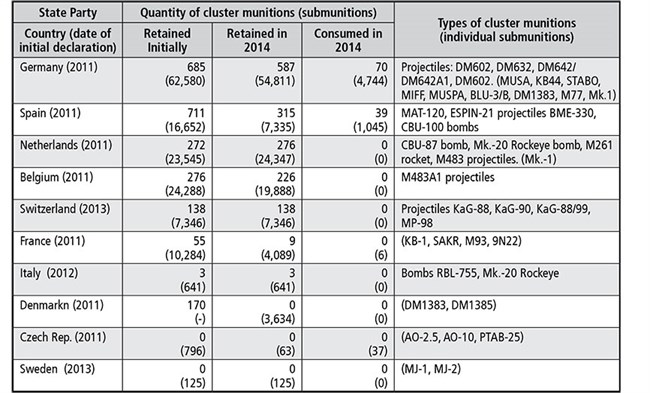

Article 3 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions permits the retention of cluster munitions and submunitions for the development of training in detection, clearance, and destruction techniques, and for the development of counter-measures such as armor to protect troops and equipment from the weapons.

The CMC questioned the need for this provision when the convention was negotiated, as it saw no compelling reason to retain live cluster munitions and explosive submunitions for research and training purposes. In their transparency reports, statements and letters, and implementation legislation, most States Parties have expressed the view that there is no need to retain any live cluster munitions or explosive submunitions for training in detection, clearance, and destruction techniques, or for the development of counter-measures. This includes 18 States Parties that stockpiled cluster munitions in the past.[152]

Some States Parties that have stockpiled cluster munitions—Chile, Croatia, and Moldova—have declared the retention of inert items that have been rendered free from explosives and no longer qualify as cluster munitions or submunitions under the convention.

Despite this, 10 States Parties—all from Europe—are retaining cluster munitions for training and research purposes, as shown in the following table. The initial quantity of cluster munitions (and submunitions) retained, the quantity retained at the end of calendar year 2014, and the quantity and types used or “consumed” for permitted purposes are listed in the following table.

Cluster munitions retained for training (as of 31 December 2014)[153]

Note: The quantity totals may include individual submunitions retained, which are not contained in a delivery container.

Germany has reduced the number of cluster munitions retained by almost a quarter since 2011 by consuming them in explosive ordinance disposal (EOD) training, but remains the State Party with the highest number of retained cluster munitions.[154]

Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, and Spain have also lowered—in most cases significantly—the number of cluster munitions retained for training since their initial declarations were made. This would indicate that the initial amounts retained were likely too high, but it is still not clear if current holdings constitute the “minimum number absolutely necessary” as required by the convention for the permitted purposes.

Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland have yet to consume any of their retained cluster munitions.

States Parties Australia and the UK initially retained cluster munitions, but have since destroyed and not replaced them as of July 2015.

Czech Republic, Denmark, and Sweden are retaining individual submunitions only.

Under Article 7 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions, States Parties are obliged to submit an initial transparency measures report no later than 180 days after the convention’s entry into force for that State Party. An updated report is due by 30 April each year thereafter. The CMC encourages states to submit their Article 7 transparency reports by the deadline and provide complete information, including definitive statements.[155]

Initial reports

According to the UN Office of Disarmament Affairs website as of 1 August 2015, a total of 67 States Parties have submitted an initial transparency report as required by Article 7 of the convention, representing 80% of States Parties for which the obligation applied at that time. This compliance rate represents a slight increase from previous years.[156]

Seventeen States Parties missed the deadline to submit their initial Article 7 transparency reports, as listed in the table below. Of these states, eight had submission deadlines in 2011, two were due in 2012, three were due in 2013, four were due in 2014, and two were due in 2015.

State Parties with overdue initial Article 7 reports

Nine new States Parties have deadlines pending: Belize (28 August 2015), Canada (27 February 2016), Republic of the Congo (28 August 2015), Guinea (in September 2015), Guyana (27 September 2015), Palestine (27 December 2015), Paraguay (28 February 2016), South Africa (29 April 2016), and Slovakia (29 June 2016).[157]

El Salvador and Trinidad and Tobago have provided their initial transparency reports since the convention’s Fifth Meeting of States Parties in September 2014.

Annual reports for 2014

As of 1 August 2015, a total of 43 States Parties have submitted their annual updated transparency report covering activities in 2014: Afghanistan, Albania, Andorra, Australia, Austria, Belgium, BiH, Bulgaria, Costa Rica, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, El Salvador, France, Germany, Holy See, Iraq, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Lao PDR, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Macedonia FYR, Mauritania, Mexico, Moldova, Montenegro, Mozambique, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Peru, Portugal, San Marino, Senegal, Slovenia, Spain, Swaziland, Sweden, Switzerland, Trinidad and Tobago, and the UK.

Two dozen States Parties have yet to submit their annual updated reports for 2014, which were due by 30 April 2015: Antigua and Barbuda, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Chile, Côte d’Ivoire, Ecuador, Ghana, Grenada, Guatemala, Hungary, Lebanon, Lesotho, Lithuania, Malawi, Malta, Monaco, Nicaragua, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Samoa, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Uruguay, and Zambia.

Voluntary reporting

Voluntary transparency reports have been provided by Canada (submitted every year between 2011 and 2014), DRC (submitted in 2011, 2012, and 2014), and Palau (submitted in 2011).

Only a small number of states have used voluntary Form J to report on actions to promote universalization and discourage use of cluster munitions, list cooperation and assistance support, or report on other important matters such as their position on interpretive issues.[158]

National Implementation Legislation

According to Article 9 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions, States Parties are required to take “all appropriate legal, administrative and other measures to implement this Convention, including the imposition of penal sanctions.”[159] The CMC urges all States Parties to enact comprehensive national legislation to enforce the convention’s provisions and provide binding, enduring, and unequivocal rules.

National implementation laws

A total of 23 States Parties and signatory Iceland have enacted specific legislative measures to implement the convention’s provisions as listed in the table below. Most enacted legislation prior to ratifying the convention, often by combining the legislative process for approval of implementation and ratification.

States with implementation laws for the Convention on Cluster Munitions

A total of 11 states enacted implementing legislation prior to the convention’s August 2010 entry into force, while 13 states have enacted implementation legislation in the period since.[160]

Since Cluster Munition Monitor 2014 was published in September 2014:

- Canada’s Prohibiting Cluster Munitions Act received its royal assent on 6 November 2014 and took effect on 16 March 2015.[161]

- Iceland enacted Law 83 in July 2015, which approves its ratification of the convention and imposes penal sanctions of between six months and four years imprisonment as well as fines for violations of its ban on the use, production, transfer, and stockpiling of cluster munitions.[162]

- Spain enacted amendments that took effect on 30 July 2015, incorporating the provisions of the Convention on Cluster Munitions into its 1998 implementing legislation for the Mine Ban Treaty.[163] Previously, in 2010, Spain amended its penal code to provide penal sanctions for violations of the Convention on Cluster Munitions.

Legislation under consideration

At least 20 States Parties have stated that they are planning or are in the process of drafting, reviewing, or adopting specific legislative measures to implement the convention: Afghanistan, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Republic of the Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Croatia, Ghana, Grenada, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Lesotho, Malawi, Mali, Niger, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Sierra Leone, Swaziland, Togo, and Zambia.

Existing law deemed sufficient

At least 28 States Parties have indicated that their existing laws will suffice to enforce their adherence to the convention: Albania, Andorra, BiH, Bulgaria, Chile, Costa Rica, Denmark, El Salvador, Guinea-Bissau, Holy See, Iraq, Lithuania, FYR Macedonia, Malta, Mauritania, Mexico, Moldova, Montenegro, Netherlands, Nicaragua, Peru, Portugal, San Marino, Senegal, Slovenia, Tunisia, Trinidad and Tobago, and Uruguay.

During the reporting period, El Salvador listed its ratification decree under national implementation measures in its transparency report.[164] Trinidad and Tobago also reported existing legislation under national implementation measures.

Status unknown

The status of national implementation measures is unknown or unclear in another 17 States Parties, including many that have not submitted their initial Article 7 transparency report.[165]

During the Oslo Process and the final negotiations in Dublin where the Convention on Cluster Munitions was adopted on 30 May 2008, it appeared that there was not a uniform view on some important issues related to interpretation and implementation of the convention. The CMC encourages States Parties and signatories that have not yet done so to express their views on the following issues of concern so that common understandings can be reached:

- The prohibition on assistance during joint military operations with states not party that may use cluster munitions (“interoperability”);

- The prohibitions on transit and foreign stockpiling of cluster munitions; and

- The prohibition on investment in production of cluster munitions.

A number of States Parties and signatories to the convention have elaborated their views on these issues, including through Article 7 transparency reports, statements at meetings, parliamentary debates, and direct communications with the CMC and the Monitor. Several strong implementation laws provide useful models for how to implement certain provisions of the convention. Yet, as of 31 July 2015, 38 States Parties had not articulated their views on even one of these interpretive issues.[166]

More than 400 US Department of State cables made public by Wikileaks in 2010–2011 demonstrate how the US—despite not participating in the Oslo Process—made numerous attempts to influence its allies, partners, and other states on the content of the draft Convention on Cluster Munitions, especially with respect to interoperability.[167] The cables also show that the US has stockpiled and may continue to be storing cluster munitions in a number of States Parties.

Interoperability and the prohibition on assistance

Article 1 of the convention obliges States Parties “never under any circumstances to…assist, encourage or induce anyone to engage in any activity prohibited to a State Party under this Convention.” Yet during the Oslo Process, some states expressed concern about the application of the prohibition on assistance during joint military operations with countries that have not joined the convention. In response to these “interoperability” concerns, Article 21 on “Relations with States not Party to this Convention” was included in the convention. The CMC has strongly criticized Article 21 for being politically motivated and for leaving a degree of ambiguity about how the prohibition on assistance would be applied in joint military operations.

Article 21 states that States Parties “may engage in military cooperation and operations with States not party to this Convention that might engage in activities prohibited to a State Party.” It does not, however, negate a State Party’s obligations under Article 1 to “never under any circumstances” assist with prohibited acts. The article also requires States Parties to discourage use of cluster munitions by those not party and to encourage them to join the convention. Together, Article 1 and Article 21 should have a unified and coherent purpose, as the convention cannot both require states parties to discourage the use of cluster munitions and, by implication, allow them to encourage it. Furthermore, to interpret Article 21 as qualifying Article 1 would run counter to the object and purpose of the convention, which is to eliminate cluster munitions and the harm they cause to civilians.

The CMC’s position is therefore, that States Parties must not intentionally or deliberately assist, induce, or encourage any activity prohibited under the Convention on Cluster Munitions, even when engaging in joint operations with states not party.

At least 34 States Parties and signatories have agreed that the convention’s Article 21 provision on interoperability should not be read as allowing states to avoid their specific obligation under Article 1 to prohibit assistance with prohibited acts.[168]

States Parties Australia, Canada, Japan, and the UK have indicated their support for the contrary view that the convention’s Article 1 prohibition on assistance with prohibited acts may be overridden by the interoperability provisions contained in Article 21:

- Australia’s Criminal Code Amendment (Cluster Munitions Prohibition) Act 2012 has been heavily criticized for allowing Australian military personnel to assist with cluster munition use by states not party. Section 72.41 of Australia’s implementing legislation “provides a defence to the offence provisions where prohibited conduct takes place in the course of military cooperation or operations with a foreign country that is not a party to the Convention.”[169] During joint or coalition military operations, Australian Defence Force personnel could help plan operations or provide intelligence for, and/or contribute logistical support to coalition members during which a state not party uses cluster munitions.[170]

- Canada’s Prohibiting Cluster Munitions Act 2014 has elicited similar criticism for its provisions allowing Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) and public officials to “direct or authorize” an act that “may involve” a state not party performing activities prohibited under the convention during joint military operations.[171] In March 2015, the Chief of Defense Staff issued a directive it said “reflects the requirements of the Act” to “provide direction on prohibited and permitted activities to [Canadian Armed Forces] personnel who might become involved in cluster munition related activities.”[172]

- Japan has been reluctant to publicly discuss its interpretation of Article 21.[173] However, in a June 2008 State Department cable, a senior Japanese official apparently told the US that Japan interprets the convention as enabling the US and Japan to continue to engage in military cooperation and conduct operations that involve US-owned cluster munitions.[174]

- The UK’s 2010 implementation law permits assistance with a number of acts prohibited under the convention if the assistance occurs during joint military operations.[175] In addition, the UK stated in 2011 that its interpretation of the Article 21 is that “notwithstanding the provisions of Article 1 [prohibition on assistance], Article 21(3) allows States Parties to participate in military operations and cooperation with non-States Parties who may use cluster munitions. UK law and operational practice reflect this.”[176]

States Parties France, the Netherlands, and Spain have provided the view that Article 21 allows for military cooperation in joint operations, but have not indicated the forms of assistance allowed. Spain’s 2015 implementation law establishes that military cooperation and participation in military operations by Spain, its military personnel, or its nationals with states that are not party to the Convention on Cluster Munitions and that use of cluster munitions is not prohibited.[177] After Spain’s opposition parties called for the draft legislation to prohibit Spain’s involvement at all times in military operations with other states that use cluster munitions, the draft legislation was adjusted to incorporate the positive obligations of Article 21(2) of the convention, requiring Spain to work for universalization and to discourage the use of cluster munitions.

In addition, while there is no evidence to indicate that the US has used cluster munitions in the “Operation Inherent Resolve” military action against IS forces that began last year in Syria and Iraq, the CMC has warned the US against using any cluster munitions in the operation.[178] The Monitor requested information from the UK on how it is engaging in the Iraq portion of the joint operation with the US and other states that have not banned cluster munitions. In May 2015, the Foreign and Commonwealth Offfice (FCO) responded:

The prohibition on the UK’s use of cluster munitions is reflected in our operational targeting policy documents which outline how UK armed forces will operate, including with coalition partners. Restrictions on the use of weapons and national caveats imposed during coalition operations are a normal part of coalition operations. These directives include the national, operationally-specific, rules of engagement profiles and national caveats which will ensure that any action is within the parameters of UK law.[179]

Transit and foreign stockpiling

The CMC has stated that the injunction to not provide any form of direct or indirect assistance with prohibited acts contained in Article 1 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions should be seen as banning the transit of cluster munitions across or through the national territory, airspace, or waters of a State Party. The convention should be seen as banning the stockpiling of cluster munitions by a state not party on the territory of a State Party.

At least 32 States Parties and signatories have declared that transit and foreign stockpiling are prohibited by the convention.[180]

States Parties that have indicated support for the opposite view—that transit and foreign stockpiling are not prohibited by the convention—include Australia, Canada, Japan, the Netherlands, Portugal, Sweden, and the UK.

US stockpiling and transit

States Parties Norway and the UK have confirmed that the US has removed its stockpiled cluster munitions from their respective territories. The UK announced in 2010 that there were now “no foreign stockpiles of cluster munitions in the UK or on any UK territory.”[181] According to a Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs official, the US removed its stockpiled cluster munitions from Norway in 2010.[182]

The US Department of State cables released by Wikileaks show that the US has stockpiled and may still store cluster munitions in States Parties Afghanistan, Germany, Italy, Japan, and Spain, as well as in non-signatories Israel, Qatar, and perhaps Kuwait:

- A US cable dated December 2008 states, “The United States currently has a very small stockpile of cluster munitions in Afghanistan.”[183]

- Germany has not expressed clear views on the convention’s prohibition on foreign stockpiling of cluster munitions, but according to a December 2008 cable, it has engaged with the US on the matter of cluster munitions that may be stockpiled by the US in Germany.[184]

- Italy, Spain, and Qatar were identified by the US in a November 2008 cable as “states in which the US stores cluster munitions,” even though apparently Qatar “may be unaware of US cluster munitions stockpiles in the country.”[185] Spain reported in 2011 that it is in the process of informing the states not party with which it cooperates in joint military operations of its international obligations with respect to the prohibition of storage of prohibited weapons on territory under its jurisdiction or control.[186]

- Japan maintains that US military bases in Japan are under US jurisdiction and control, so the possession of cluster munitions by US forces does not violate the national law or the convention. A December 2008 cable states that Japan “recognizes U.S. forces in Japan are not under Japan’s control and hence the GOJ [government of Japan] cannot compel them to take action or to penalize them.”[187]

- According to a cable detailing the inaugural meeting on 1 May 2008 of the “U.S.-Israeli Cluster Munitions Working Group (CMWG),” until US cluster munitions are transferred from the War Reserve Stockpiles for use by Israel in wartime, “they are considered to be under U.S. title, and U.S. legislation now prevents such a transfer of any cluster munitions with less than a one percent failure rate.”[188]

- According to a May 2007 cable, the US may store cluster munitions in Kuwait.[189]

Disinvestment

A number of States Parties and the CMC view the convention’s Article 1 ban on assistance with prohibited acts as constituting a prohibition on investment in the production of cluster munitions.

A total of 10 States Parties have enacted legislation that explicitly prohibits investment in cluster munitions, as shown in the table.[190]

Disinvestment laws on cluster munitions

Four States Parties enacted legislation on cluster munitions containing provisions on disinvestment prior to the convention’s 1 August 2010 entry into force, while six have have adopted disinvestment laws in the period since.

In this reporting period: