Landmine Monitor 2023

The Impact

Jump to a specific section of the chapter:

Contamination | Casualties | Clearance | Risk Education | Victim Assistance

This chapter highlights developments and challenges in assessing and addressing the negative impact caused by the use of antipersonnel landmines. It reflects on the progress of States Parties toward meeting their Mine Ban Treaty obligations and the objectives contained in the five-year Oslo Action Plan, adopted at the treaty’s Fourth Review Conference in November 2019.

The first part of this overview covers landmine contamination and casualties, while the second part focuses on efforts to address the impact of mine use through clearance, risk education, and victim assistance. These make up three of the five core components or “pillars” of mine action.

In 2022, at least 4,710 people were killed or injured by mines and explosive remnants of war (ERW) globally. This represents a fall from 5,544 casualties recorded in 2021, and is primarily due to a significant decline in the number of reported casualties in Afghanistan, where the data collection system was under-resourced. Syria recorded the most mine/ERW casualties of any state in 2022, followed by Ukraine.

New casualties were recorded in 49 states in 2022, including 38 States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty. States Parties accounted for almost two-thirds of all annual casualties. Most casualties in 2022 occurred in conflict-affected countries that are contaminated by improvised mines.

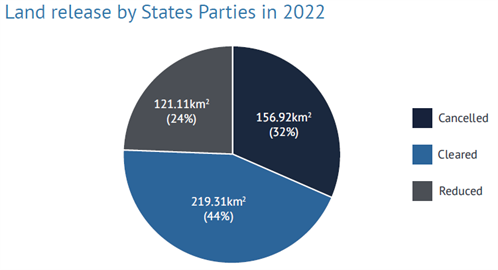

Positive progress was reported, as 497.34km² of land known or suspected to be contaminated by antipersonnel landmines was released by States Parties with clearance obligations in 2022—almost double the area released in 2021, which totaled 276km2. Of the land released in 2022, 219.31km² was cleared, while 121.11km² was reduced via technical survey and 156.92km² was canceled through non-technical survey. In total, 169,276 antipersonnel mines were cleared and destroyed during clearance activities in 2022.

Despite this progress, the outlook for meeting the aspirational goal set by States Parties in 2014 “to clear all mined areas as soon as possible, to the fullest extent by 2025,” looks unlikely to be met.[1] No State Party reported completing clearance of contaminated areas during 2022, as required by Article 5 of the Mine Ban Treaty. Four States Parties with clearance obligations did not undertake any clearance activities in 2022, while another six did not formally report on their Article 5 obligations. Twenty States Parties have deadlines to meet their obligations under Article 5 either before or during 2025, but very few appear on track to meet their deadline.

Ongoing armed conflict in some States Parties and the use of improvised mines is compounding the complexity of the challenge of survey and clearance. As of October 2023, at least 24 States Parties are believed or known to have improvised mine contamination.[2]

Risk education on the threat from mines and ERW is a crucial intervention, as people continue to live and work in contaminated areas. Of the 33 States Parties with clearance obligations, 28 reported or are known to have provided risk education during 2022. These activities focused predominantly on rural communities in contaminated areas, as well as on internally displaced persons (IDPs) and returnees. Children and men remained the primary at-risk groups. National capacity-building, often via training-of-trainers programs, and the integration of risk education into other humanitarian, development, and protection initiatives, took place in the majority of States Parties that reported carrying out risk education in 2022.

Victim assistance is an enduring obligation that requires sustained efforts, including by States Parties that have been declared mine-free as well as those that remain contaminated. At least 37 States Parties are recognized to have responsibility for significant numbers of mine victims. Broader disability rights frameworks, and a newly-updated International Mine Action Standard (IMAS) on victim assistance, aid victim assistance efforts in these states. Yet a lack of funding remained a major impediment to addressing victims’ needs, while health systems suffered from economic crises, armed conflict, and natural disasters in several countries. The work of States Parties, and their implementing partners, to meet the commitments made in the Oslo Action Plan to improve victim assistance—including emergency medical response, ongoing healthcare and rehabilitation, psychosocial support, and socio-economic inclusion—remains vital.

Assessing The Impact

The use of antipersonnel mines has caused widespread contamination globally over the past 80 years. A total of 85 countries—63 States Parties and 22 states not party—and five other areas have or are believed to have land contaminated by antipersonnel landmines on their territory.

Antipersonnel mine contamination

Antipersonnel mine contamination in States Parties

States Parties with Article 5 obligations

Under Article 5 of the Mine Ban Treaty, States Parties with contamination are required to clear all antipersonnel mines as soon as possible, but not later than 10 years after the entry into force of the treaty for that country.

As of October 2023, a total of 63 States Parties had reported mined areas under their jurisdiction or control. This includes 33 States Parties with current Article 5 clearance obligations.

States Parties with declared Article 5 obligations as of October 2023

|

State Party |

Deadline |

State Party |

Deadline |

|

Afghanistan |

1 March 2025 |

Nigeria |

31 December 2025 |

|

Angola |

31 December 2025 |

Oman |

1 February 2025 |

|

Argentina* |

1 March 2026 |

Palestine |

1 June 2028 |

|

BiH |

1 March 2027 |

Peru |

31 December 2024 |

|

Cambodia |

31 December 2025 |

Senegal |

1 March 2026 |

|

Chad |

1 January 2025 |

Serbia |

31 December 2024 |

|

Colombia |

31 December 2025 |

Somalia |

1 October 2027 |

|

Croatia |

1 March 2026 |

South Sudan |

9 July 2026 |

|

Cyprus** |

1 July 2025 |

Sri Lanka |

1 June 2028 |

|

DRC |

31 December 2025 |

Sudan |

1 April 2027 |

|

Ecuador |

31 December 2025 |

Tajikistan |

31 December 2025 |

|

Eritrea*** |

31 December 2020 |

Thailand |

31 December 2026 |

|

Ethiopia |

31 December 2025 |

Türkiye |

31 December 2025 |

|

Guinea-Bissau |

31 December 2024 |

Ukraine |

1 December 2023 |

|

Iraq |

1 February 2028 |

Yemen |

1 March 2028 |

|

Mauritania |

31 December 2026 |

Zimbabwe |

31 December 2025 |

|

Niger |

31 December 2024 |

|

|

*Argentina was mine-affected by virtue of its assertion of sovereignty over the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas. The United Kingdom (UK) also claims sovereignty and exercises control over the territory and completed mine clearance in 2020. Argentina has not yet acknowledged completion.

**Cyprus has stated that no areas contaminated by antipersonnel mines remain under its control.

***Eritrea has been in non-compliance with the treaty since missing its Article 5 deadline in 2020.

Another ten States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty—Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Mali, Mexico, Mozambique, the Philippines, Togo, Tunisia, and Venezuela—may be contaminated by improvised landmines. These States Parties should provide information on whether the devices are victim-activated and, if so, clear them under Article 5. The Mine Ban Treaty comprehensively prohibits all types of victim-activated explosive devices, regardless of how they were manufactured (improvised or factory-made).

States Parties that have completed clearance

No States Parties reported completing clearance of antipersonnel mines in 2022. The last States Parties to do so were Chile and the United Kingdom (UK), in 2020. Since the treaty came into force on 1 March 1999, a total of 30 States Parties have reported clearance of all antipersonnel mines from their territory.[3] State Party El Salvador completed mine clearance in 1994, before the treaty came into force.

States Parties that have declared fulfillment of clearance obligations since 1999[4]

|

1999 |

Bulgaria |

2010 |

Nicaragua* |

|

2002 |

Costa Rica |

2012 |

Republic of the Congo, Denmark, Gambia, Jordan, Uganda |

|

2004 |

Djibouti, Honduras |

2013 |

Bhutan, Germany, Hungary, Venezuela* |

|

2005 |

Guatemala, Suriname |

2014 |

Burundi |

|

2006 |

North Macedonia |

2015 |

Mozambique* |

|

2007 |

Eswatini |

2017 |

Algeria* |

|

2008 |

France, Malawi |

2020 |

Chile, UK |

|

2009 |

Albania, Greece, Rwanda, Tunisia,* Zambia |

|

|

*Algeria, Mozambique, Nicaragua, and Tunisia have reported, or are suspected to have, residual contamination. Mozambique, Tunisia, and Venezuela are suspected to have improvised mine contamination.

Several States Parties that had declared themselves free of antipersonnel mines later discovered previously unknown contamination or had to verify that areas had been cleared to humanitarian standards.[5] Burundi, Germany, Greece, Hungary, and Jordan each declared fulfillment of their Article 5 obligations several years after their initial declaration of completion.

Guinea-Bissau, Mauritania, and Nigeria each reported discovering further contamination after declaring completion under Article 5, and submitted extension requests in 2020–2021.

Extent of contamination in States Parties

Eight States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty—Afghanistan, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Cambodia, Croatia, Ethiopia, Iraq, Türkiye, and Ukraine—have reported massive antipersonnel landmine contamination (more than 100km²). The extent of contamination in Ethiopia and Ukraine cannot be reliably determined until survey has been conducted.[6] In Ukraine, the ongoing conflict is adding to the contamination.

Large contamination by antipersonnel landmines (20–99km²) is reported in five States Parties: Angola, Chad, Eritrea, Thailand, and Yemen.

Medium contamination (5–19km²) is reported in six States Parties: Mauritania, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Tajikistan, and Zimbabwe.

Twelve States Parties have reported less than 5km² of contamination: Colombia, Cyprus, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Ecuador, Guinea-Bissau, Niger, Oman, Palestine, Peru, Senegal, Serbia, and Somalia.

The extent of contamination in Nigeria is not known.

Estimated antipersonnel mine contamination in States Parties

|

Massive (more than 100km²) |

Large (20–99km²) |

Medium (5–19km²) |

Small (less than 5km²) |

Unknown

|

|

Afghanistan BiH Cambodia Croatia Ethiopia* Iraq Türkiye Ukraine*

|

Angola Chad Eritrea Thailand Yemen

|

Mauritania South Sudan Sri Lanka Sudan Tajikistan Zimbabwe |

Colombia Cyprus** DRC Ecuador Guinea-Bissau Niger Oman Palestine Peru Senegal Serbia Somalia |

Nigeria

|

*Ethiopia and Ukraine have reported massive contamination, though this cannot be reliably verified until survey has been conducted.

**Cyprus has stated that no areas contaminated by antipersonnel mines remain under its control.

Americas

As of the end of 2022, Colombia reported 3.8km² of antipersonnel mine contamination, across 76 municipalities and 16 departments. The contamination, mostly from improvised landmines, covered 261 confirmed hazardous areas (CHAs) totaling 1.95km² and 312 suspected hazardous areas (SHAs) totaling 1.86km².[7] Colombia reported that 80 new SHAs totaling 0.74km² and 93 CHAs totaling 0.61km² were identified in 2022.[8] Eighteen municipalities were declared mine-free in 2022. A further 157 municipalities in Colombia were known or suspected to be affected by antipersonnel landmines, though the extent of their contamination remained unknown. This includes 122 municipalities that were not accessible for security reasons.[9]

Ecuador and Peru each have a very small amount of remaining mine contamination. As of the end of 2022, Ecuador had 0.04km² of contaminated land (0.03km² CHA and 0.01km² SHA), containing approximately 2,941 mines.[10] Mine contamination in Peru totaled 0.34km² across 87 SHAs.[11] Peru reported to have completed clearance in Tiwinza sector during 2022, with is remaining mine contamination located in the sectors of Achuime, Cenepa, and Santiago.[12]

East and South Asia and the Pacific

Afghanistan reported antipersonnel mine contamination totaling 144.93km² (119.94km² CHA and 24.99km² SHA) as of the end of 2022. This included 51.14km² of improvised landmine contamination. In addition, Afghanistan reported 35.89km2 of mixed contamination from antipersonnel mines, antivehicle mines, and ERW.[13]

As of the end of 2022, Cambodia reported 7,392 SHAs with landmine contamination totaling 681.28km².[14] The northwest region bordering Thailand is heavily affected, while other parts of the country in the east and northeast are primarily affected by ERW, including cluster munition remnants. Much of the remaining mine contamination in Cambodia and Thailand is along their shared border; where despite improved cross-border cooperation between the two states, access remains a challenge due to a lack of border demarcation.[15]

Contamination in Sri Lanka remains in the Northern, Eastern, and North Central provinces, and has increased due to newly-identified, previously unknown mined areas.[16] As of the end of 2022, Sri Lanka reported 15.43km² of contaminated land covering 534 CHAs (13.52km²) and 87 SHAs (1.91km²).[17] The most significant mine contamination (14.58km²) is found in five districts of Northern province, which were the site of intense fighting during the civil war.[18]

Thailand reported 29.69km² of contamination across six provinces, with 18.13km² classified as CHA and 11.56km² as SHA.[19] Some of this contamination is on the border with Cambodia, affecting land yet to be demarcated, though efforts were made in 2022 to strengthen bilateral cooperation on demining.[20] Thailand has also experienced the use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) by insurgents in the south. Yet the extent of this contamination is unknown and has not been recorded by the Thailand Mine Action Center (TMAC).[21]

Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia

BiH reported extensive antipersonnel mine contamination totaling 869.61km2 (18.17km2 CHA and 851.44km2 SHA) as of the end of 2022.[22] This represented a decrease from the 922.37km² reported as of the end of 2021, primarily due to cancelation of SHA.[23]

As of the end of 2022, Croatia reported mine contamination totaling 149.7km² (99.4km² CHA and 50.3km² SHA) across six of its 21 counties, down from 204.4km2 reported as of the end of 2021. An additional 19.8km² of contaminated land in Croatia is under military control.[24] Most of the remaining contamination is reported to be in forested areas, where clearance projects are aligned with conservation and nature protection regulations.[25]

Cyprus is believed to have 1.24km² of antipersonnel and antivehicle landmine contamination (0.43km² CHA and 0.81km² SHA) across 29 areas. Yet the contamination is reported to be only in Turkish-controlled Northern Cyprus and in the buffer zone, and not in territory under the effective control of Cyprus.[26]

Serbia reported 0.39km² of mine contamination across three areas in Bujanovac municipality, all classified as SHA.[27] Areas suspected to be contaminated after explosions caused by forest fires in Bujanovac in 2019 and 2021 have not yet been surveyed.[28]

Tajikistan reported 11.45km² of antipersonnel mine contamination (6.95km² CHA and 4.5km² SHA) as of the end of 2022. The majority of the SHA is located on the Tajikistan-Uzbekistan border, covering 3.25km² across 54 areas.[29]

Türkiye reported 133.39km² CHA, across 3,701 areas. Most contaminated areas are along its borders with Iran, Iraq, and Syria, whilst 918 of the areas are not in border regions.[30] Türkiye began conducting non-technical survey in June 2021, and intends to complete survey of all contaminated areas by the end of 2023.[31] In addition to mines laid by Turkish security forces, there is contamination from improvised mines and other explosive devices laid by non-state armed groups (NSAGs).[32]

Ukraine has experienced significant new contamination since Russia’s full-scale invasion of the country in February 2022.[33] This has prevented Ukraine from progressing clearance to meet its Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline. As of March 2023, only 50km2 had been identified as contaminated by mines/ERW via non-technical survey, with clearance efforts mainly focused on critical infrastructure and population centers.[34] In June 2023, the country’s National Mine Action Authority (NMAA) reported that 160,000km² of Ukrainian territory had been exposed to conflict and would require survey.[35] In contrast, in 2018, Ukraine provided an estimate of 7,000km² of undifferentiated contamination, including by antipersonnel mines, in government-controlled areas within the eastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk, and another 14,000km² in areas not controlled by the government.[36]

Middle East and North Africa

Iraq is dealing with contamination by improvised landmines in areas liberated from the Islamic State—in addition to legacy mine contamination from the 1980–1988 war with Iran, the 1991 Gulf War, and the 2003 invasion by a United States (US)-led coalition. As of the end of 2022, Iraq reported 1,189.09km² of antipersonnel mine contamination, and an additional 530.8km² of contamination from IEDs, including improvised mines. Most of the contamination is located in territory under the government of Federal Iraq.[37]

Oman reported that all mined areas were cleared before it joined the Mine Ban Treaty, but that the process is being “re-inspected” to address any residual risk.[38] In 2021, Oman developed a workplan to release its remaining 0.51km² of suspected mined areas by April 2024, without providing further details on this estimate.[39] As of October 2023, Oman had not submitted an Article 7 report to update on progress made in 2022.

During 2022, Palestine made significant progress in understanding the type and extent of its landmine contamination. Palestine reported 0.32km² of mine contamination in total, of which 0.25km² was contaminated with antipersonnel mines and 0.07km² was mixed contamination, comprised of both antipersonnel and antivehicle mines.[40] Minefields located in Jenin and the Jordan Valley were pending clearance as of March 2023.[41]

Up to 2022, the scale and impact of conflict in Yemen had prevented a clear understanding of the level of mine contamination, which was estimated to be massive. However, as of the end of 2022, estimated contamination with antipersonnel mines, including improvised mines, had been reduced to 51.97km2 (33.69km² CHA and 18.28km² SHA). This new calculation is based on information collected through a baseline survey that started in 2022. The baseline survey is expected to be completed in 2023.[42]

Sub-Saharan Africa

As of the end of 2022, Angola reported total antipersonnel mine contamination of 68km² across 16 provinces and 1,142 areas. A total of 65.36km2 was classified as CHA and 2.64km2 as SHA. Cuando Cubango and Moxico are the most heavily contaminated provinces, with 16.8km² and 11.8km² respectively.[43]

As of the end of 2022, Chad had identified a total of 120 hazardous areas, with 72 classified as CHA, in the provinces of Borkou, Ennedi, and Tibesti. Contamination was reported to be mixed including improvised mines, and covered a total area of 77.69km² (56.02km² CHA and21.68km² SHA). Over half of Chad’s contamination (43.24km²) was in Tibesti province.[44]

The remaining mine contamination in the DRC is small. In March 2022, after a national survey and clean-up of the national database, the DRC reported contamination totaling 0.4km² across 37 CHAs, but highlighted that it still had areas left to survey on the borders with South Sudan and Uganda.[45] Improvised landmine contamination has been identified in Ituri and North-Kivu provinces.[46] These improvised mines were reportedly emplaced on agricultural land, to prevent farmers working in their fields.[47] As of October 2023, the DRC reported a total of 0.32km2 of CHA contaminated with antipersonnel mines.[48]

Eritrea has not reported on the extent of its contamination since 2014, when it was estimated to have 33.5km² of contaminated land.[49] Eritrea is in violation of the Mine Ban Treaty by virtue of its failure to meet its 2020 clearance deadline and submit an extension request.

In June 2022, Ethiopia reported contamination of 726.07km² across 152 areas in six provinces; the same figure reported since April 2020. Of this, 29 areas were classified as CHA (3.52km²) and 123 areas as SHA (722.55km²).[50] Most SHAs are located in the Somali region. It is believed that the baseline figure is an overestimate, and that only 2% of these areas contain landmines.[51] The conflict in northern Ethiopia since late 2020 has resulted in contamination from explosive ordnance, though the extent and type is yet to be fully established.[52] Separate armed conflicts are ongoing in other regions of Ethiopia, such Benishangul Gumuz and Oromia.[53]

Guinea-Bissau declared fulfillment of its clearance obligations in December 2012, but in 2021 reported the presence of “previously unknown mined areas” containing antipersonnel mines, antivehicle mines, and ERW. A total of nine CHAs were reported across the northern provinces of Cacheu and Oio, and the southern provinces of Quebo and Tombali. An additional 43 areas were suspected to contain both mines and ERW. As of the end of 2022, Guinea-Bissau reported that the nine CHAs totaled 1.09km², with no further progress made on surveying 43 previously reported SHAs.[54] Guinea-Bissau is believed to also be contaminated by improvised mines.[55]

Mauritania declared clearance of all known contamination in 2018, but later identified new mined areas.[56] As of the end of 2022, Mauritania reported 16km² of landmine contamination including at least 0.54km² contaminated by antivehicle mines.[57]

In 2021, Niger reported 0.18km² of CHA, adjacent to a military post in Madama, in the Agadez region.[58] This figure has not changed since its Article 5 extension request was granted in 2020. In 2022, Niger reported that it could not guarantee clearance would be completed by its 2024 deadline, due to challenges including weather conditions, lack of funding, and the threat posed by NSAGs.[59] Niger is also contaminated by improvised mines.[60]

In 2019, Nigeria reported improvised mine contamination.[61] The contamination affects mainly the three northeastern states of Adamawa, Borno, and Yobe.[62] Nigeria was granted a second extension to its Article 5 clearance deadline in 2021. As of May 2023, Nigeria had not yet been able to conduct a comprehensive survey to determine the full extent of contamination.[63]

Senegal reported that after non-technical survey undertaken in 2020, a total of 37 hazardous areas had been identified, covering 0.49km².[64] As of the end of 2022, Senegal reported that 21 CHAs covering an area of 0.21km² remained to be addressed. Areas with known contamination were located in Bignona, Goudomp, Oussouye, and Zinguinchor departments.[65] In addition, 11 SHAs of unknown size were reported but had not yet been surveyed due to insecurity.[66] Eight SHAs were located in Bignona and three in Goudomp. Another 116 localities also remained to be surveyed, including 101 areas in Bignona, 11 in Ziguinchor, and four in Oussouye.[67]

In September 2021, Somalia reported 6.1km² of antipersonnel mine contamination, within its total 161.8km² of mixed contamination, which included antivehicle landmines.[68] Somalia has also reported increased use of improvised mines.[69] In 2022, Somalia reported progress toward understanding the nature and extent of contamination, including in the states of Jubaland and Puntland. As of the end of 2022, Somalia reported a total of 124.23km² of mixed contamination including antipersonnel mines (55.47km² CHA and 68.76km² SHA). Of this, 0.56km² contains only antipersonnel mines.[70] Some areas in Somalia remain unsurveyed due to conflict.[71]

South Sudan reported 5.41km² of landmine contamination as of May 2023, with 3.05km² CHA and 2.36km² SHA across eight states. The largest SHA, in Jonglei state, totaled 1.65km².[72]

As of the end of 2021, Sudan reported 13.28km2 of antipersonnel mine contamination, with 3.32km² CHA and 9.96km² SHA across the states of Blue Nile, South Kordofan, and West Kordofan.[73] The United Nations Integrated Transition Assistance Mission in Sudan (UNITAMS) reported the identification of 255 new SHAs and CHAs during 2022.[74] However, as of March 2023, UNMAS reported that 138.09km2 of the recorded 172km2 of contaminated land had been released.[75]

As of the end of 2022, contamination in Zimbabwe totaled 18.31km2. This contamination is all classified as CHA and is mostly located along Zimbabwe’s border with Mozambique in four provinces, with one inland minefield in Matabeleland North province.[76]

Suspected improvised (antipersonnel) mine contamination in States Parties

IEDs that are designed to be exploded by the presence, proximity, or contact of a person are prohibited under the Mine Ban Treaty.[77]

The Oslo Action Plan recognizes that the “new use of antipersonnel mines in recent conflicts, including those of an improvised nature, has added to the remaining challenge of some States Parties in fulfilling their commitments under Article 5.” Action 21 of the Oslo Action Plan lays out the commitment for States Parties affected by improvised mines to clear them under Article 5 of the Mine Ban Treaty, and to provide regular information on the extent of contamination, disaggregated by type of mine, in their annual transparency reporting under Article 7.

As of October 2023, at least 24 States Parties are believed or known to have improvised mine contamination.[78] Ten of these states have yet to clarify if any contamination with improvised mines includes victim-activated devices, which are prohibited by the Mine Ban Treaty. Some of these states had not yet submitted an Article 7 report for calendar year 2022.

In Burkina Faso, IED use by NSAGs has been recorded since 2016. Pressure-plate improvised antivehicle mines have been increasingly used since 2018, due to the introduction of measures which block signals to command-detonated IEDs. Casualties from improvised landmines were recorded in 2020, 2021, and 2022 in Burkina Faso. Most incidents involved vehicles such as cars, carts, and bicycles, though some incidents involved people walking.[79]

Cameroon originally declared that there were no mined areas under its jurisdiction or control, but since 2014, improvised mines used by Boko Haram have caused casualties, particularly in the north on the border with Nigeria.[80] The IED trigger mechanisms used are reportedly diverse and include victim-activated devices.[81] An increase in IED use was reported in the Far North region of Cameroon since 2021, targeting state security forces.[82] The extent of contamination is unknown but thought to be small. Most incidents in past years involved people traveling by vehicle. In 2022, only one incident involving an improvised mine was recorded, when a device exploded as military personnel were attempting to defuse it.[83]

In the Central African Republic, conflict between government forces and rebel groups has escalated since 2020, with an increase in the use of improvised mines and IEDs, particularly in the west.[84] The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) reported that antipersonnel mines were discovered for the first time in the country in April 2022, noting “an alarming rise” in civilian casualties from explosive devices.[85] UNOCHA stated that while the devices were “mostly laid on the ground, they explode by the presence, proximity or contact of a person or vehicle.”[86] In February 2023, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) expressed concern that incidents involving landmines and other explosive devices had increased.[87] The Central African Republic last submitted an Article 7 transparency report in 2004.

Mali has confirmed antivehicle landmine contamination, and since 2017 has seen a significant rise in incidents caused by IEDs in the center of the country.[88] All casualties were traveling by vehicle. The Monitor recorded improvised mines and unspecified mine types in Mali in 2022, including in incidents resulting in casualties that were recorded by the National Secretariat to Counter the Proliferation of Small Arms and Light Weapons.[89]

Mexico used its Article 7 report todetail the use of IEDs and “artisanal mines” by cartels in the state of Michoacán de Ocampo during 2022. The nature of the fuzing of these devices was not known.[90] Such devices appear to include primarily command-detonated roadside bombs and improvised antivehicle landmines.[91] In February 2022, the Secretariat of National Defense deployed troops to the state to conduct clearance operations.[92] Mexican soldiers were reported to have cleared more than 500 improvised mines between February and April 2022.[93]

Mozambique was declared mine-free in 2015. It faces a possible threat of contamination from improvised mines due to use of IEDs by insurgents in the northern province of Cabo Delgado.[94] The World Health Organization (WHO) reported two IED incidents occurring in March 2023.[95]

The Philippines has reported that it has no remaining mined areas, yet risk education is still conducted due to ERW and IED contamination.[96] Casualties from improvised mines continued to be reported in 2022.[97] In November 2022, at the Twentieth Meeting of States Parties, the Philippines reiterated that “landmines” are used in “sporadic attacks” by NSAGs including the New People’s Army.[98] The use of improvised mines by other NSAGs has been documented on the southern island of Mindanao.[99]

Togo lastsubmitted an Article 7 report in 2003. It has not reported any mined areas under its jurisdiction or control. Yet improvised mine use by NSAGs has been reported since 2022 and incidents have caused military and civilian casualties, including children traveling by cart.[100]

Tunisia declared completion of mine clearance in 2009.[101] Yet there is known to be residual contamination. There have also been reports of both military and civilian casualties from new use of landmines—including improvised antipersonnel mines—in the last five years.[102]

Venezuela reported meeting its Article 5 obligations in 2013.[103] In August 2018, local media reports said that Venezuelan military personnel were wounded by an antipersonnel landmine in Catatumbo municipality, Zulia state, along the border with Colombia.[104] Colombian NSAGs were reported in 2022 to be using improvised mines in the area.[105] After a confrontation in March 2021 between Venezuelan troops and dissidents of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, FARC) in Victoria, Apure state, a Venezuelan non-governmental organization (NGO) stated that mines “similar to those used in Colombia” were found in the area.[106] Mine contamination was later confirmed by a member of parliament and the Ministry of Defense.[107] Venezuela reported that the military would clear the area, but also requested UN support to clear mines from the border.[108] The Monitor reported eight casualties caused by improvised mines in Venezuela in 2022.[109]

States Parties with residual contamination

Five States Parties were known or suspected to have residual mine contamination in 2022.

Algeria declared fulfillment of its Article 5 obligations in December 2016, but continues to find and destroy antipersonnel mines. In 2022, Algeria reported clearance of 30.15km² along with the destruction of 1,247 antipersonnel mines; a decrease from 1,725 mines destroyed in 2021 and 8,813 in 2020. The mines were believed to have naturally migrated from areas where they were laid along the Challe and Morice Lines in the 1950s, on the borders of the country.[110]

Mine/ERW casualties have been reported in Kuwait since 1990. New casualties were reported in 2022. In 2018, there were reports that torrential rain had unearthed landmines, presumed to be remnants of the 1991 Gulf War.[111] Landmines are believed to be present mainly on Kuwait’s borders with Iraq and Saudi Arabia, in areas used by shepherds for grazing animals. Kuwait has not made a formal declaration of contamination in line with its Article 5 obligations.

Mozambique was declared mine-free in 2015 but has since reported residual and isolated mine contamination throughout the country.[112] Four small suspected mined areas, totaling 1,881m², were reported in 2018 to be located underwater in Inhambane province. Mozambique stated that it would address this contamination once the water level had receded, allowing access.[113] Mozambique has provided no further updates on progress in these areas since 2019.[114]

Nicaragua declared completion of clearance under Article 5 in April 2010, but has since found residual contamination. Twenty-nine reports of ordnance from the public during 2022 resulted in the clearance of 1,337m² and the destruction of 17 antipersonnel mines and 412 ERW.[115]

Tunisia reported in 2009 the clearance of all minefields laid in 1976 and 1980 along its borders with Algeria and Libya. Yet since then, it has reported a residual mine/ERW threat dating from World War II in El Hamma, Mareth, and Matmata in the south; Faiedh and Kasserine in the center of the country; Cap-Bon in the north; and other areas in the northwest.[116] Tunisia has not provided updates on efforts to clear this residual contamination.

Antipersonnel mine contamination in states not party and other areas

Twenty-two states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty and five other areas have, or are believed to have, land contaminated by antipersonnel mines on their territory.

States not party and other areas with antipersonnel mine contamination

|

Abkhazia |

Israel |

North Korea |

|

Armenia |

Kosovo |

Pakistan |

|

Azerbaijan |

Kyrgyzstan |

Russia |

|

China |

Lao PDR |

Somaliland |

|

Cuba |

Lebanon |

South Korea |

|

Egypt |

Libya |

Syria |

|

Georgia |

Morocco |

Uzbekistan |

|

India |

Myanmar |

Vietnam |

|

Iran |

Nagorno-Karabakh |

Western Sahara |

Note: other areas are indicated in italics.

States not party

The extent of contamination is unknown in most states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty.

The extent of mine contamination in Azerbaijan is not known. After the conflict with Armenia ended in September 2020, Azerbaijan gained control of areas along the former line of contact—an area heavily contaminated with mines/ERW.[117] In 2023, the Azerbaijan National Agency for Mine Action (ANAMA) reported that it would prioritize conducting systematic survey of suspected mined areas to gain a better understanding of the extent of contamination.[118]

In Georgia, five landmine contaminated areas remain in Tbilisi-administered territory, totaling 2.25km² (0.026km² contaminated by antipersonnel mines and 2.23km² of mixed contamination including antivehicle mines). The largest minefield (2.2km2) is known as the “Red Bridge”—a seven kilometer-long mine belt along Georgia’s borders with Azerbaijan and Armenia. The full extent of contamination in these areas has yet to be confirmed as survey is ongoing.[119]

Israel reported some 90km² of contamination in 2017 (41.58km² CHA and 48.51km² SHA), including in areas in the West Bank.[120] This did not include mined areas “deemed essential to Israel’s security.” No updates on contamination have been provided since 2017, though Israel reported progress in re-surveying mine-affected areas and clearance of 0.18km² in 2020, and 0.56km² in 2021.[121] A total of 140 mines and ERW were reported cleared in 2021, with 2.7km² of land released in the Negev desert, along the border with Egypt.[122] In January 2023, media reported on Israel’s demining operations in the Golan Heights.[123]

As of the end of 2022, Lebanon reported 16.91km² of CHA, including 0.16km2 contaminated by improvised mines.[124] Lebanon reported 0.015km² of newly-discovered antipersonnel mine contamination in 2022, and 0.025km² of newly-discovered improvised mine contamination.[125]

In South Korea, the extent of contamination is unknown, but more than 1 million mines have been laid in the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) on the border with North Korea.[126] New casualties were reported in 2022, with one civilian killed and two soldiers injured.[127]

Landmines are also known or suspected to be located along the borders of several other states not party, including Armenia, China, Kyrgyzstan, Morocco, North Korea, and Uzbekistan.

Ongoing armed conflict, insecurity, and improvised mine contamination also affects states not party Egypt, India, Libya, Myanmar, Pakistan, and Syria.

Other areas

Five other areas, unable to accede to the Mine Ban Treaty due to their political status, are known to be contaminated.

As of the end of 2021, mine-affected areas in Kosovo totaled 0.58km², of which 0.21km2 was CHA and 0.37km2 was SHA. Kosovo reported an additional 0.42km² of mixed contamination (consisting of antipersonnel mines and cluster munition remnants).[128]

Abkhazia reported to have cleared its remaining mined area totaling 0.01km². Some landmines continue to be scattered, along with ERW, around the site of a previous ammunition explosion at Primorsky, and will be addressed through explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) call-outs.[129]

Before the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan in September 2020, Nagorno-Karabakh was reported to have 6.75km² of contamination. This included 5.62km² of antipersonnel mine contamination, 0.23km² of antivehicle mine contamination, and 0.9km² of mixed contamination.[130] The only demining operator in Nagorno-Karabakh, the HALO Trust, reported that its operational area had reduced by 60% after the conflict, with the presence of Russian peacekeepers resulting in access constraints. In May 2022, the HALO Trust completed clearance of all known contamination in Nagorno-Karabakh’s capital city, Stepanakert.[131] The Lachin corridor, which provided access between Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia, was under a blockade as of December 2022, and a lack of access to fuel and essential supplies posed a major challenge to deminers.[132] As this report went to print, Azerbaijan appeared to have regained control of Nagorno-Karabakh after a brief conflict on 19 September 2023.[133]

Contamination in Somaliland totaled 3.4km² (1.1km² of antipersonnel mine contamination and 2.3km² of mixed contamination).[134] In September 2023, the HALO Trust reported that it was conducting a baseline assessment to obtain a more accurate estimate of contamination.[135] Most of the mined areas in Somaliland are barrier or perimeter minefields around military bases.[136]

Western Sahara’s minefields lie east of the Berm, a 2,700km-long wall built during the 1975–1991 conflict, dividing control of the territory between Morocco in the west and the Polisario Front in the east. The contaminated area covers 211.72km² (86.06km² CHA and 125.66km² SHA).[137] These minefields are contaminated with antivehicle mines, though a small number of antipersonnel landmines have also been found.[138] There have been no updates on the extent of contamination since most survey and clearance activities were suspended in 2021.[139] UNMAS reported in April 2023 that, following a request from the United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO), its implementing partner SafeLane Global was preparing to resume humanitarian demining operations in Western Sahara in May 2023.[140]

Landmines and ERW, including cluster munition remnants, remain a major threat and continue to cause indiscriminate harm globally.[141]

At least 4,710 people were killed or injured by mines/ERW in 2022. Of that total, at least 1,661 were killed while 3,015 were injured. For 34 casualties, the survival outcome was not known.[142] Mine/ERW casualties were recorded in 49 countries and two other areas during 2022.

States and areas with mine/ERW casualties in 2022

|

Americas |

East and South Asia and the Pacific |

Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia |

Middle East and North Africa |

Sub-Saharan Africa |

|

Colombia Mexico Venezuela |

Afghanistan Bangladesh Cambodia India Lao PDR Myanmar Nepal Pakistan Philippines Sri Lanka Thailand |

Armenia Azerbaijan BiH Croatia Tajikistan Türkiye Ukraine |

Algeria Egypt Iran Iraq Kuwait Lebanon Libya Palestine Syria Yemen

|

Angola Benin Burkina Faso Cameroon Central African Rep. Chad DRC Mali Mauritania Niger Nigeria Senegal Somalia Somaliland South Sudan Sudan Togo Uganda Western Sahara Zimbabwe |

Note: States Parties are indicated in bold. Other areas are indicated in italics.

State not party Syria recorded the highest number of new mine/ERW casualties in 2022 for the third consecutive year. Casualties in Syria decreased from 1,227 in 2021 to 834 during 2022.

Ukraine recorded the second-highest total in 2022, replacing Afghanistan as having the highest number of annual casualties among States Parties. From the Russian invasion on 24 February 2022, to the end of the year, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) recorded 608 civilian mine/ERW casualties in Ukraine. Whilst casualties in Ukraine are acknowledged to be under-reported, this represents more than a tenfold increase, with 58 civilian casualties recorded in 2021. OHCHR reported that “on current trajectory,” the number of civilian mine/ERW casualties in Ukraine was expected to rise significantly in 2023.[143]

State Party Yemenrecorded 582 casualties in 2022, up from 528 in 2021. During 2022, it was reported that violence in Yemen had reduced sharply since an October 2021 truce, but that “the number of people injured or killed by landmines and unexploded ordnance remained the same or higher, highlighting the dangers of these remnants of war even in peace time.”[144]

State not party Myanmar saw a significant rise in casualties, from 368 in 2021 to 545 in 2022. In 2022, for the first time, mine/ERW casualties were recorded in every state and region of the country, except Naypyidaw.[145]

Countries with over 500 mine/ERW casualties in 2022

|

Country |

Casualties in 2022 |

|

Syria |

834 |

|

Ukraine |

608 |

|

Yemen |

582 |

|

Myanmar |

545 |

Note: States Parties are indicated in bold.

Many mine/ERW casualties go unrecorded each year globally, and therefore are not captured in the Monitor data. Some states do not have functional casualty surveillance systems in place, while other forms of reporting are often inadequate or lack disaggregation.

Afghanistan saw recorded casualties decrease from 1,074 in 2021 to 303 in 2022. Yet UNMAS noted that data for 2022 did not reflect all victims of mine/ERW incidents during the year.

Casualties and Mine Ban Treaty status in 2022

Mine/ERW casualties were recorded in 37 States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty during 2022, representing over two-thirds (65%, or 3,040) of all annual casualties. Eight States Parties each recorded more than 100 casualties.[146]

States Parties with over 100 mine/ERW casualties in 2022

|

State Party |

Casualties |

|

Ukraine |

608 |

|

Yemen |

582 |

|

Nigeria |

431 |

|

Afghanistan |

303 |

|

Mali |

182 |

|

Iraq |

169 |

|

Colombia |

145 |

|

Angola |

107 |

Note: States Parties are indicated in bold.

During 2022, the Monitor recorded a total of 1,632 mine/ERW casualties in 12 states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty, with just over half (51%) of those casualties recorded in Syria (834).[147] For the fifth year running, Myanmar accounted for the next highest casualty total among states not party, with 545 casualties—a further increase from 368 in 2021 and 280 in 2022.[148]

In other areas Somaliland and Western Sahara, a combined 38 casualties were reported in 2022.

Casualty demographics[149]

The devastating and disproportionate impact of mines and ERW on civilians is again reflected in the Monitor casualty statistics for 2022. Civilians made up 85% of all casualties recorded in 2022 where the civilian, deminer, or military status of the casualty was known.

There were at least 27 casualties among deminers in eight countries.[150]The actual number was far higher, as the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) reported that during the first seven weeks of the conflict in Ukraine in 2022, there were 102 casualties among deminers (29 killed and 73 injured).[151]

Civilian status of mine/ERW casualties in 2022[152]

|

Civilian |

3,693 |

|

Deminer |

27 |

|

Military |

621 |

|

Unknown |

369 |

At least 1,171 child casualties were recorded in 2022. Children made up almost half (49%) of civilian casualties and just over one-third (35%) of all casualties in 2022, where the age group was known.[153] Children were killed (386) or injured (782) by mines/ERW in 35 states and one other area.[154] The survival outcome for three children was not reported. In 2022, as in previous years, the vast majority of child casualties were boys (79%) where the gender was recorded.[155] ERW remained the item causing most child casualties (518, or 44%), followed by improvised mines (223, or 19%).[156] Children made up three-quarters (518, or 66%) of ERW casualties.[157]

Men and boys accounted for the majority of casualties in 2022, accounting for 2,095 (or 84%) where the sex was known (2,499). Women and girls accounted for 404 casualties (or 16%).

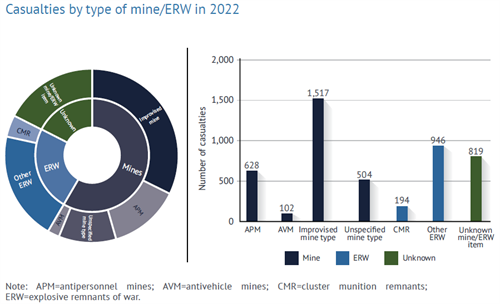

Casualties by device type

In 2022, improvised mines, most of which are believed to act as antipersonnel mines, accounted for the highest number of casualties for the seventh consecutive year.

Collectively, landmines of all types caused the majority of recorded casualties (2,751, or 58%) during 2022. This includes factory-made antipersonnel mines (628, or 13%), victim-activated improvised mines (1,517, or 32%), antivehicle mines (102, or 2%), and unspecified mine types (504, or 11%).

Most casualties attributed to unspecified mine types in 2022 were reported in Yemen (382).

Cluster munition remnants caused at least 194 casualties in 2022, while other ERW caused 946 casualties.[158] A total of 819 casualties resulted from mines/ERW that were not disaggregated.

Addressing The Impact

Mine clearance in 2022

Article 5 of the Mine Ban Treaty obligates each State Party to destroy or ensure the destruction of all antipersonnel landmines in mined areas under its jurisdiction or control as soon as possible, but not later than 10 years after entry into force of the treaty for that State Party.

States Parties with clearance obligations reported clearance totaling 219.31km² in 2022.[159] At least 169,276 landmines were cleared and destroyed during the year.

This represents a significant increase from the reported 132.52km² of land cleared in 2021.

Non-technical and technical survey also contribute to the overall amount of land that is released and returned to local populations for productive use. In 2022, a total of 497.34km² of land was released by States Parties with Article 5 obligations, of which 219.31km2 was released through clearance operations, 121.11km² via technical survey, and 156.92km² via non-technical survey.

Land release by States Parties in 2022[160]

Antipersonnel mine clearance in States Parties in 2021–2022[161]

|

State Party |

2021 |

2022 |

||

|

Clearance (km²) |

APM destroyed |

Clearance (km²) |

APM destroyed |

|

|

Afghanistan |

17.69 |

7,652 |

11.12 |

5,464 |

|

Angola |

5.91 |

3,617 |

5.87 |

3,342 |

|

Argentina* |

N/A |

N/A |

0 |

0 |

|

BiH |

0.06 |

1,717 |

0.91 |

3,180 |

|

Cambodia |

43.73 |

6,087 |

88.47 |

13,708 |

|

Chad |

1.45 |

15 |

6.21 |

0 |

|

Colombia |

1.94 |

204 |

0.96 |

247 |

|

Croatia |

34.49 |

1,462 |

40.2 |

1,107 |

|

Cyprus** |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

DRC |

0.01 |

12 |

0.03 |

4 |

|

Ecuador |

0 |

0 |

0.002 |

17 |

|

Eritrea |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

|

Ethiopia |

0 |

0 |

N/R |

N/R |

|

Guinea-Bissau |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Iraq |

11.07 |

4,831 |

11.23 |

5,702 |

|

Mauritania |

0.1 |

13 |

0.13 |

0 |

|

Niger |

0 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

|

Nigeria |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

|

Oman |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

|

Palestine |

0 |

0 |

0.03 |

37 |

|

Peru |

0.01 |

188 |

0.02 |

529 |

|

Senegal |

0 |

0 |

0.08 |

N/R |

|

Serbia |

0.29 |

9 |

0.17 |

0 |

|

Somalia |

***0.25 |

13 |

***5.56 |

360 |

|

South Sudan |

0.25 |

31 |

0.28 |

284 |

|

Sri Lanka |

4.10 |

26,804 |

11.80 |

29,599 |

|

Sudan |

0.03 |

17 |

N/R |

32 |

|

Tajikistan |

0.37 |

2,219 |

0.58 |

1,197 |

|

Thailand |

0.53 |

19,002 |

0.33 |

11,421 |

|

Türkiye |

0.41 |

14,125 |

1.29 |

58,078 |

|

Ukraine |

***2.90 |

N/R |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Yemen |

****4.49 |

3,365 |

***31.91 |

3,864 |

|

Zimbabwe |

2.44 |

26,457 |

2.13 |

31,104 |

|

Total |

132.52 |

117,847 |

219.31 |

169,276 |

Note: APM=antipersonnel mines; N/R=not reported; N/A=not applicable.

*Argentina was mine-affected by virtue of its assertion of sovereignty over the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas. The UK also claims sovereignty and exercises control over the territory, and completed mine clearance in 2020. Argentina has not yet acknowledged completion.

**Cyprus has stated that no areas contaminated by antipersonnel mines remain under Cypriot control.

***Clearance of mixed/undifferentiated contamination that included antipersonnel mines.

****Land reported as cleared and reduced.

In 2022, Cambodia cleared the most land (88.47km²), followed by Croatia (40.2km²). Türkiye cleared and destroyed the most landmines in 2022, clearing a total of 58,078 mines from only 1.29km² of land. Thailand and Zimbabwe cleared a large number of antipersonnel mines from relatively small areas, indicating the density of mines laid in their contaminated border areas.

Twelve States Parties cleared under 1km² in 2022: BiH, Colombia, DRC, Ecuador, Mauritania, Palestine, Peru, Senegal, Serbia, South Sudan, Tajikistan, and Thailand.

Four States Parties with Article 5 obligations did not report any clearance in 2022: Argentina, Cyprus, Guinea-Bissau, Niger.

Argentina was mine-affected by virtue of its assertion of sovereignty over the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas. The UK also claims sovereignty and exercises control over the territory, where it completed mine clearance in 2020. As of October 2023, Argentina has not yet acknowledged completion.[162]

Cyprus reported that it did not undertake clearance as no areas contaminated by antipersonnel mines remained under its control.[163]

Guinea-Bissau reported that it was working to rebuild the capacity required to resume survey and clearance operations, following the discovery of new contamination in 2021.[164]

Niger did not conduct any clearance operations in 2022 due to challenging weather conditions, a lack of funding, insecurity, and a new priority to fight the proliferation of illicit weapons.[165]

As of October 2023, six States Parties with Article 5 obligations—the DRC, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Oman, and Sudan—had not submitted updated Article 7 transparency reports to outline their progress on clearance.

In the DRC, from October 2021 to September 2022, the US Department of State reported that, through its implementing partners, 33,770m² of land had been cleared and 4,170m² had been released. During this period, 15 mines and 117 ERW were destroyed.[166] As of October 2023, the DRC had not yet submitted its Article 7 report for calendar year 2022. However, it reported to the Monitor that 27,318m2 was cleared and four antipersonnel mines were destroyed during 2022.[167]

Eritrea has not reported any clearance since it last submitted an updated Article 7 transparency report in 2014.[168]

Ethiopia has not provided any new figures for antipersonnel mine clearance since its Article 7 report for January 2019–April 2020, when it reported 1.75km² cleared and 128 antipersonnel mines destroyed.[169] As of March 2021, Ethiopia reported that it had cleared 0.05m² in Fiq district in the Somali region, clearing and destroying 46 antivehicle mines.[170]

Nigeria reported that no land release operations were conducted by humanitarian mine action operators in 2022. The Nigerian Armed Forces conducted mine clearance activities for military purposes, but no further information was shared.[171]

Oman reported the “re-clearance” of 0.08km² of land in 2018, but did not provide any further details.[172] In 2019, Oman reported re-clearance of 11 mined areas in Al-Mughsail, in Dhofar governorate, totaling 0.13km², but no mines were found.[173] In 2020, Oman reported that no mine/ERW incidents had taken place in the country in 20 years, and that formerly mined areas had been cleared, released, and were populated. [174] As of October 2023, Oman had not yet submitted Article 7 reports covering calendar years 2021–2022.

In 2021, Sudan reported clearing 0.03km2 of antipersonnel mine contaminated land, destroying 17 antipersonnel mines and 57 antivehicle mines.[175] In 2022, Sudan reported that access to Blue Nile, Darfur, and South Kordofan had improved following the Juba Agreement for Peace, enabling the assessment of roads for humanitarian assistance and population movement.[176] Yet Sudan also cited ongoing insecurity, a lack of funding, the COVID-19 pandemic, and weather conditions as key challenges that have negatively impacted progress.[177] As of October 2023, Sudan had not yet submitted its Article 7 report for calendar year 2022. However, UNITAMS reported that 32 antipersonnel landmines, 14 antivehicle mines, and 2,347 items of unexploded ordnance (UXO) were destroyed in 2022.[178]

Improvised mines were reported cleared in 2022 in States Parties Afghanistan, Angola, Colombia, Iraq, Mali, and Yemen.

In 2022, Afghanistan released 10.66km² (2.05km2 cleared, 0.04km2 reduced, and 8.57km2 canceled) of land contaminated with improvised mines, clearing 3,032 improvised mines.[179] Angola destroyed two improvised mines.[180] All mines cleared in Colombia were improvised mines.[181] Iraq released 31.39km2 of land contaminated with IEDs—and reported to have destroyed a total of 10,577 IEDs—including improvised mines and other explosive devices.[182] Mali destroyed 82 improvised mines.[183] Yemen did not sufficiently disaggregate land release figures for improvised mines. For areas released with mixed or undifferentiated contamination, 23 antipersonnel/improvised mines were recorded as being destroyed along with 5,539 IEDs, without further specification.[184]

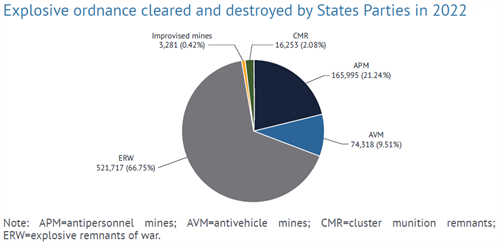

Explosive ordnance cleared and destroyed by States Parties in 2022[185]

Article 5 deadlines and extension requests

If a State Party believes that it will be unable to clear and destroy all antipersonnel landmines contaminating its territory within 10 years after entry into force of the Mine Ban Treaty for the country, it must request a deadline extension under Article 5 for a period of up to 10 years.[186]

Clearance progress to 2025

At the Third Review Conference of the Mine Ban Treaty in 2014, States Parties agreed to intensify efforts to complete their respective time-bound obligations with the urgency that the completion work requires. This included a commitment to clear all mined areas as soon as possible, but not later than 2025.[187]

As of October 2023, a total of 20 States Parties had deadlines to meet their Article 5 obligations before or no later than 2025. Thirteen States Parties have Article 5 deadlines later than 2025.

States Parties with clearance deadlines beyond 2025

|

Clearance deadline |

States Parties |

|

2026 |

Argentina, Croatia, Mauritania, Senegal, South Sudan, Thailand |

|

2027 |

BiH, Somalia, Sudan |

|

2028 |

Iraq, Palestine, Sri Lanka, Yemen |

In 2022, four States Parties—Afghanistan, Ecuador, Guinea-Bissau, and Serbia—requested extensions to their clearance deadlines up to 2025. Another four States Parties—Argentina, Sudan, Thailand, and Yemen—requested extensions beyond 2025. All requests were granted during the Twentieth Meeting of States Parties in November 2022.[188] In March 2023, Ukraine submitted its third extension request, for a 10-year extension until 1 December 2033.[189] The request will be considered at the Twenty-First Meeting of States Parties in November 2023.

Of the following States Parties with Article 5 clearance deadlines in 2025 or earlier, it appears that only very few could complete clearance within their deadlines.

The main purpose of the extension request submitted by Afghanistan in July 2022 was for additional time to understand how the demining sector in the country will develop. Based on this, Afghanistan planned to submit a further detailed extension request by 31 March 2024.[190]

Angola’s annual land release since 2019 has been below the projected annual land release of 17km² detailed in its 2019–2025 workplan.[191] Angola has stated that it is undertaking every effort to meet its current Article 5 deadline of December 2025. However, it is believed that Angola will realistically be able to complete clearance of known minefields by 2028, with the possibility of extending its deadline to 2030 depending on the availability of funds.[192]

Cambodia has reported its commitment to meet its Article 5 deadline of 2025, and has started to raise additional funds to facilitate an increase in demining capacity.[193] In May 2023, Cambodia submitted a revised workplan with projected release of 345.3km2 of mined areas in 2023, and 168km2 annually in both 2024 and 2025. Cambodia cited challenges to meeting its deadline as the lack of demarcated border areas with Thailand, and a potential shortfall in the required financial resources.[194]

The annual clearance output in Chad increased significantly in 2022.[195] Yet it is unclear if the reported land release includes areas contaminated by antipersonnel mines, due to a lack of data on the geographical areas cleared and types of ordnance present. Given the current clearance rate and due to limited funding, it is unlikely that Chad will meet its 2025 deadline.[196]

The DRC reported that it is on track to meet its clearance deadline. Yet ongoing insecurity is a concern, and given the limited land release output in 2022 and in previous years, it is unlikely that the DRC will be able to meet its 2025 deadline.[197]

Ecuador’sprogress toward meeting its Article 5 deadline in December 2025 is uncertain. The rate of clearance has been slow over the past five years, despite the small extent of remaining contamination. Ecuador did not conduct any clearance in 2021 and does not appear to have met its annual target of 0.01km² clearance for 2022, as projected in its fourth extension request.[198]

In Ethiopia, there has been little progress on clearance and survey over the last two years, including since a November 2022 peace agreement.[199] As of October 2023, Ethiopia had not submitted its Article 7 report for 2022. Ethiopia is unlikely to meet its December 2025 deadline.

In 2021, Guinea-Bissau reported suspected mine/ERW contamination and was granted an extension to its Article 5 clearance deadline to 31 December 2022.[200] Guinea-Bissau submitted another extension request in 2022 for two additional years, which was granted. The request projected a preparatory phase during 2022; an implementation phase in 2023 to conduct non-technical survey; and marking, emergency spot tasks, and clearance in 2023–2024.[201] It is uncertain whether Guinea-Bissau will meet its December 2024 clearance deadline, as delays in the preparatory phase were reported in June 2023.[202]

Niger did not conduct any clearance operations in 2021–2022, amid a lack of funding and ongoing insecurity.[203] Despite having only small contamination (0.18km2), it is not expected that Niger will meet its Article 5 deadline in 2024.

Oman was thought to be on track to complete clearance, with a plan to re-clear seven areas from February 2021 to April 2024.[204] Yet as of October 2023, Oman had not submitted an Article 7 report to update States Parties on its progress during calendar year 2022.

Clearance output in Peru has been limited, but increased in 2022. At the current clearance rate, Peru would be on track to complete clearance of mined areas by its December 2024 deadline. Yet in September 2023, at an open consultation on the extension process, a representative of Peru stated that it would be requesting another extension to its Article 5 deadline.[205]

In March 2022, Serbia requested a third extension, of 21 months, in order to undertake non-technical survey of newly-discovered SHA in Bujanovac municipality and create a workplan. The request was granted. It is expected that Serbia will submit another Article 5 extension request to clear any confirmed contamination after the completion of non-technical survey.[206]

Tajikistan reported that current capacity would need to be increased to meet its deadline.[207]

Türkiye cleared three times more mine-contaminated land in 2022 than in 2021, but still does not appear to be on target to meet its 2025 deadline.[208]

Ongoing conflict and insecurity are likely to impact the ability of Colombia, Nigeria, and Ukraine to meet their Article 5 deadlines. Colombia reported that it will not meet its deadline due to ongoing use of improvised mines by NSAGs.[209] In Nigeria, conflict in the northeast has hindered the mapping of contamination and restricted survey and clearance activities.[210] Prior to the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Ukraine did not have control of parts of the eastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk, which prevented it from clearing contaminated areas in these territories.[211] Ongoing hostilities in 2022 and 2023 have added to the extent of contamination and prevented access for survey and clearance operations. As a result, in March 2023, Ukraine submitted a 10-year extension request under Article 5.[212]

Zimbabwe is confident of meeting its deadline of December 2025, given the current capacity of demining operators and with only 5.7% of its contamination remaining.[213]

Summary of Article 5 deadline extension requests

|

State Party |

Original deadline |

Extension period (no. of request) |

Current deadline |

Status |

|

Afghanistan |

1 March 2013 |

10 years (1st) 2 years (2nd) |

1 March 2025 |

Expected to request another extension |

|

Angola |

1 January 2013 |

5 years (1st) 8 years (2nd) |

31 December 2025 |

Behind target

|

|

Argentina* |

1 March 2010 |

10 years (1st) 3 years (2nd) 3 years (3rd) |

1 March 2026 |

Has not acknowledged completion |

|

BiH |

1 March 2009 |

10 years (1st) 2 years (2nd) 6 years (3rd) |

1 March 2027 |

Behind target |

|

Cambodia |

1 January 2010 |

10 years (1st) 6 years (2nd) |

31 December 2025 |

On target |

|

Chad |

1 November 2009 |

1 year and 2 months (1st) 3 years (2nd) 6 years (3rd) 5 years (4th) |

1 January 2025 |

Behind target

|

|

Colombia |

1 March 2011 |

10 years (1st) 4 years and 10 months (2nd) |

31 December 2025 |

Expected to request another extension |

|

Croatia |

1 March 2009 |

10 years (1st) 7 years (2nd) |

1 March 2026 |

On target |

|

Cyprus |

1 July 2013 |

3 years (1st) 3 years (2nd) 3 years (3rd) 3 years (4th) |

1 July 2025 |

Expected to request another extension |

|

DRC |

1 November 2012 |

2 years and 2 months (1st) 6 years (2nd) 1 year and 6 months (3rd) 3 years and 6 months (4th) |

31 December 2025 |

Behind target |

|

Ecuador |

1 October 2009 |

8 years (1st) 3 months (2nd) 5 years (3rd) 3 years (4th) |

31 December 2025 |

Progress to target uncertain |

|

Eritrea |

1 February 2012 |

3 years (1st) 5 years (2nd) 11 months (3rd) |

31 December 2020 |

In violation of the treaty by not requesting a new extension |

|

Ethiopia |

1 June 2015 |

5 years (1st) 5 years and 7 months (2nd) |

31 December 2025 |

Behind target |

|

Guinea-Bissau |

1 November 2011 |

2 months (1st) 1 year (2nd) 2 years (3rd) |

31 December 2024 |

Progress to target uncertain |

|

Iraq |

1 February 2018 |

10 years (1st) |

1 February 2028 |

Behind target |

|

Mauritania |

1 January 2011 |

5 years (1st) 5 years (2nd) 1 year (3rd) 5 years (4th) |

31 December 2026 |

Behind target |

|

Niger** |

1 September 2009 |

2 years (1st) 1 year (2nd) 4 years (3rd) 4 years (4th) |

31 December 2024 |

Behind target |

|

Nigeria*** |

1 March 2012 |

1 year (1st) 4 years (2nd) |

31 December 2025 |

Behind target |

|

Oman |

1 February 2025 |

N/A |

1 February 2025 |

Progress to target uncertain |

|

Palestine |

1 June 2028 |

N/A |

1 June 2028 |

Progress to target uncertain |

|

Peru |

1 March 2009 |

8 years (1st) 7 years and 10 months (2nd) |

31 December 2024 |

Expected to request another extension |

|

Senegal |

1 March 2009 |

7 years (1st) 5 years (2nd) 5 years (3rd) |

1 March 2026 |

Progress to target uncertain |

|

Serbia |

1 March 2014 |

5 years (1st) 4 years (2nd) 1 year and |

31 December 2024 |

Expected to request another extension |

|

Somalia |

1 October 2022 |

5 years (1st) |

1 October 2027 |

On target |

|

South Sudan |

9 July 2021 |

5 years (1st) |

9 July 2026 |

Behind target |

|

Sri Lanka |

1 June 2028 |

N/A |

1 June 2028 |

On target |

|

Sudan |

1 April 2014 |

5 years (1st) 4 years (2nd) 4 years (3rd) |

1 April 2027 |

Progress to target uncertain |

|

Tajikistan |

1 April 2010 |

10 years (1st) 5 years and |

31 December 2025 |

Behind target |

|

Thailand |

1 May 2009 |

9 years and 5 years (2nd) 3 years and |

31 December 2026 |

On target |

|

Türkiye |

1 March 2014 |

8 years (1st) 3 years and 10 months (2nd) |

31 December 2025 |

Behind target |

|

Ukraine |

1 June 2016 |

5 years (1st) 2 years and |

1 December 2023 |

Requested extension until |

|

Yemen |

1 March 2009 |

6 years (1st) 5 years (2nd) 3 years (3rd) 5 years (4th) |

1 March 2028 |

Progress to target uncertain |

|

Zimbabwe |

1 March 2009 |

1 year and 10 months (1st) 2 years (2nd) 2 years (3rd) 3 years (4th) 8 years (5th) |

31 December 2025 |

On target |

Note: N/A=not applicable.

*Argentina and the UK both claim sovereignty over the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas. The UK completed mine clearance of the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas in 2020, but Argentina has not yet acknowledged completion.

** In 2008, Niger declared that there were no remaining areas suspected to contain antipersonnel mines. In May 2012, Niger informed States Parties of suspected and confirmed mined areas. Only in July 2013, Niger requested its first extension to the deadline that had already expired in 2009.

*** In 2019, seven years after its initial deadline, Nigeria declared newly-mined areas and in 2020, submitted a first extension request to its initial, already-expired deadline.

Extension requests submitted in 2022–2023

In 2022, eight States Parties submitted requests to extend their Article 5 clearance deadlines: Afghanistan, Argentina, Ecuador, Guinea-Bissau, Serbia, Sudan, Thailand, and Yemen. These requests were all granted during the Twentieth Meeting of States Parties in November 2022.

On 4 July 2022, Afghanistan submitted a request to extend its clearance deadline for two years until March 2025. It was expected that a further detailed request would be submitted in March 2024. Due to the complexity of the political situation in the country, details on the remaining contamination or an accompanying workplan could not be included in the request.[214]

Argentina was granted an extension of three years until 1 March 2026. Argentina has cited the need to verify clearance of the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas, completed by the UK in 2020, to comply with its obligations under the treaty.[215]

Ecuador was granted an extension of three years, until 31 December 2025, to clear remaining contamination of 0.04km². The remaining contaminated areas are in high altitude locations with challenging climatic conditions.[216]

Guinea-Bissau was granted a further extension to 31 December 2024 to conduct survey, as well as subsequent marking, risk education, and clearance as required.[217]

Serbia was granted a third extension during 2022 and has committed to provide an updated workplan by the treaty’s Twenty-First Meeting of States Parties in November 2023.[218]

Sudan was granted a third Article 5 deadline extension in 2022, for four additional years until 1 April 2027.[219] As of December 2021, Sudan had identified 102 hazardous areas totaling 13.28km².[220] As a result of the Juba Agreement for Peace, Sudan’s mine action program gained access to previously inaccessible areas, and expects to identify new hazardous areas close to the frontlines. However, Sudan did not provide an update on its progress in 2022.

Thailand was granted a third extension in 2022, until 31 December 2026.[221] While on target in terms of its survey and clearance plan, the lack of access to 14.31km² of contaminated land on the border with Cambodia—which has not yet been demarcated—has caused delays.[222]

Yemen was granted a fourth extension, for five years until March 2028, to continue with its baseline survey to determine the extent and impact of new mine contamination.

In March 2023, Ukraine submitted its third extension request, for 10 years, proposing a new deadline of 1 December 2033.[223] After submitting the request, Ukraine reported that the ongoing conflict has made it impossible to take measures sooner to ensure the clearance of all antipersonnel mines on territories under its jurisdiction and control.[224] Ukraine’s extension request will be considered at the Twenty-First Meeting of States Parties in November 2023.

Risk education is a core pillar of humanitarian mine action and key legal obligation under Article 5 of the Mine Ban Treaty, which requires States Parties to “provide an immediate and effective warning to the population” in all areas under their jurisdiction or control in which antipersonnel mines are known or suspected to be emplaced.

Risk education has often been omitted from Article 7 transparency reports or from updates provided by states at Mine Ban Treaty meetings.[225] Yet delivery of risk education to affected populations is a primary and often cost-effective means of preventing injuries and saving lives.

The Oslo Action Plan, adopted by States Parties at the treaty’s Fourth Review Conference in 2019, contains five actions points on risk education, contributing to renewed attention for this pillar in recent years. These actions include commitments on:

- Integrating risk education within wider humanitarian, development, protection, and education efforts, and with other mine action activities;

- Providing context-specific risk education to all affected populations and at-risk groups;

- Prioritizing people most at risk through analysis of casualty and contamination data, and through an understanding of people’s behavior and movements;

- Building national capacity to deliver risk education, which can adapt to changing needs and contexts; and

- Reporting on risk education in annual Article 7 transparency reports.[226]

In addition, the Oslo Action Plan requires States Parties to provide detailed, costed, and multi-year plans for context-specific mine risk education and reduction in affected communities.

Provision of risk education in 2022

Of the 33 States Parties with clearance obligations, 28 reported providing or are known to have provided risk education to populations at risk from antipersonnel landmine contamination in 2022. Argentina, Ecuador, Eritrea, Guinea-Bissau, and Oman did not report any risk education activities in 2022.

States Parties with clearance obligations that provided risk education in 2022

|

Afghanistan Angola BiH Cambodia Chad Colombia Croatia Cyprus DRC Ethiopia |

Iraq Mauritania Niger Nigeria Palestine Peru Senegal Serbia Somalia South Sudan |

Sri Lanka Sudan Tajikistan Thailand Türkiye Ukraine Yemen Zimbabwe |

In addition, Burkina Faso and Mali, which are both known to have improvised mine contamination, reported implementing risk education activities in 2022.

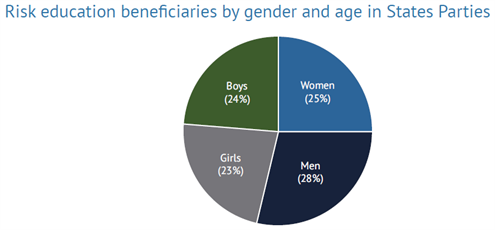

Risk education reporting and planning

In 2022, only 10 States Parties with clearance obligations that submitted an Article 7 report provided detailed updates on risk education, including beneficiary data disaggregated by sex and age: Angola, BiH, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, Iraq, Palestine, Thailand, Yemen, and Zimbabwe. Türkiye provided gender-disaggregated beneficiary data for adults but not for children. The DRC provided the Monitor directly with disaggregated beneficiary data.[227] Tajikistan provided an update with disaggregated beneficiary data at the Twentieth Meeting of States Parties in November 2022.[228]

Of the Article 5 extension requests submitted in 2022, only those submitted by Guinea-Bissau and Sudan contained detailed, costed, and multi-year plans for context-specific risk education. Ecuador, Serbia, Thailand, and Yemen confirmed that risk education would be conducted, but did not provide a budget or workplan for implementation. Afghanistan did not submit a detailed extension request. Risk education was not relevant to the extension request of Argentina, which requested time to verify clearance completed by the UK in the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas. Ukraine, in its extension request submitted in 2023, did not provide a detailed plan.[229]

Target areas and at-risk groups

To be effective, risk education must be sensitive to gender, age, and disability, and take the diverse needs and experiences of people living in affected communities into account. The consideration of target areas, high-risk groups, and the activities and behaviors that place people at risk, is crucial to the design and implementation of effective risk education programs.

In most States Parties, risk education activities in 2022 were targeted predominantly at rural communities in areas affected by contamination. Populations identified as the most vulnerable included groups that moved regularly between different locations, such as nomadic communities, hunters, herders, shepherds, agricultural workers, and people collecting natural resources. Other specific at-risk groups included children and people deliberately engaging with explosive ordnance, such as scrap metal collectors.

In addition to providing risk education to local communities, Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Iraq, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Ukraine, and Yemen identified IDPs and returnees as specific at-risk groups and targeted them for risk education.[230] In Chad, target groups included refugees fleeing violence in Sudan and crossing its eastern border.[231]

Afghanistan also targeted health workers, while Chad additionally considered nomads, animal herders, goldminers, traditional guides, and trackers as high-risk groups due to their mobility in desert areas which may be contaminated.[232] Chad, however, reported that these groups were challenging to reach.[233]